The Jewish Film Festival, which runs from May 5-15 in Toronto, is presenting biopics about the scientist Albert Einstein, the 19th century photographer Solomon Nunes Carvalho and the French politician Leon Blum.

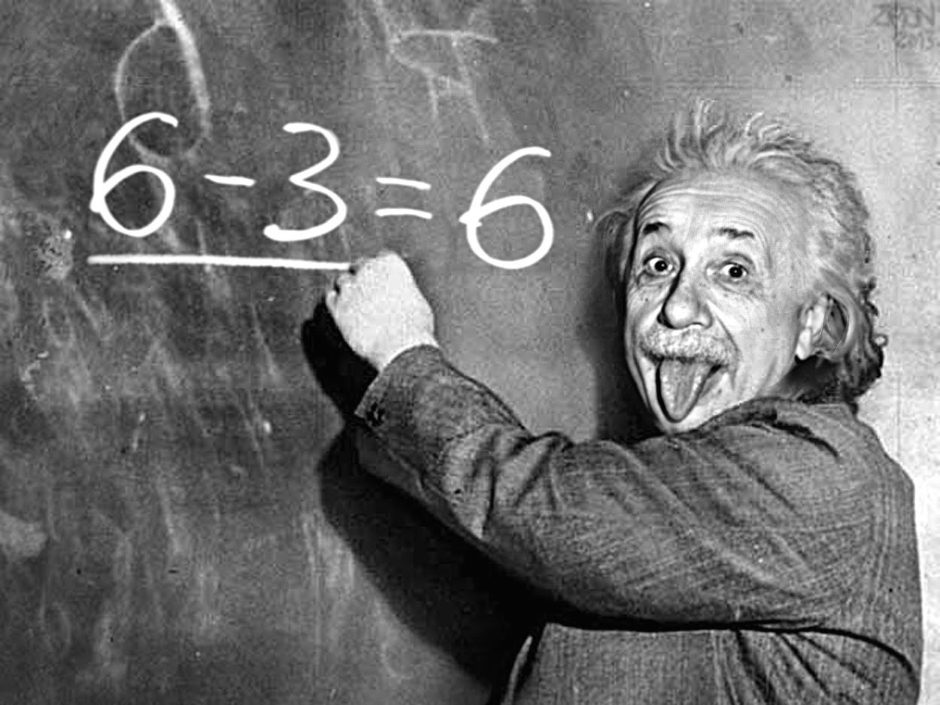

Albert Einstein and his wife, Elsa, were invited to Palestine by the Zionist movement in 1923. Noa Ben Hagai’s fascinating film, Einstein in the Holy Land (May 9 and 12), examines their whirlwind visit. It’s an appealing mix of archival footage, entries from Einstein’s travel diary and comments about Einstein by contemporary Israeli scientists.

Einstein was already a preeminent physicist when he arrived in Palestine, a British Mandate. As he toured the country, he received word he had won the Nobel Prize. Strangely enough, he did not even bother mentioning it in his diary. Perhaps he was too busy absorbing the sights, sounds and odours of the Levant.

His impression of Jerusalem was curt. The city, he observed, was “very dirty” and “orientally alien.” Nevertheless, he felt an affinity with the Yishuv, the Jewish community. He had already bequeathed his books and papers to the Hebrew University, which would be opened in two years.

Treated like royalty during his trip, Einstein paid a courtesy call on British High Commissioner Sir Herbert Samuel, toured the city and inspected new Jewish housing projects. Though impressed by the vitality and energy of the Zionist project, he was not ready to live in Palestine. “I’m a lone wolf,” wrote Einstein, who lived in Berlin. “I never belonged to one homeland.”

On the fifth day, he went to Tel Aviv, a budding metropolis he dubbed “Little Chicago.” Meir Dizengoff, the mayor, presented him with a certificate of honorary citizenship. Einstein complained he was being hounded by the press.

On day eight, he visited Haifa, Palestine’s commercial center. Having met German Jews and toured a German Templar neighborhood, he felt comfortable in Haifa. He rounded off his tour by stopping in Degania, the first kibbutz in Palestine. “The settlers are extremely likeable,” he wrote.

Einstein, a liberal internationalist, learned to love Palestine, Elsa would write. But he had no intention of settling in the country, much to the disappointment of his hosts. A generation later, when Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion offered Einstein the presidency of Israel, he declined. Like the vast majority of Jews in the Diaspora, he was attached to Israel, but was not prepared to be there physically.

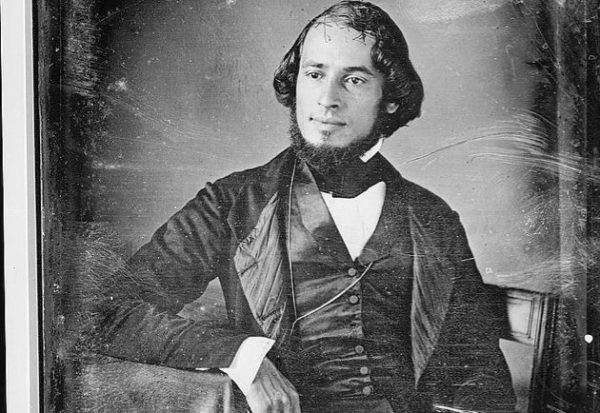

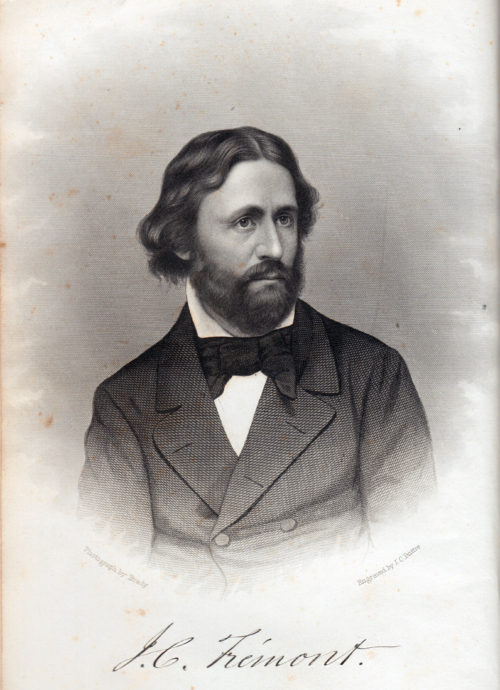

Solomon Nunes Carvalho, a 19th century Sephardi Jew, accompanied the explorer John Fremont on his fifth expedition to the American West, a vast wilderness populated by Indian tribes and teeming with herds of buffalo. As Fremont’s official photographer, Carvalho took hundreds of stunning photographs, compiling the earliest photographic record of the region.

Steve Rivo’s bracing documentary, Carvalho’s Journey (May 10 and 13), recreates his trip through the travels of contemporary photographer Robert Shlaer and through the evocative vintage photographs of the Fremont expedition.

Carvalho was born in 1815 in Charleston, South Carolina, which from 1800 to 1820 had the largest Jewish community in North America. He was a painter, but he struggled to earn a living. Fascinated by the new daguerreotype technique in photography, Carvalho became a portrait photographer.

A chance meeting with Fremont in New York City changed the course of Carvalho’s life. An advocate of westward expansion with presidential ambitions, Fremont sought to map the route of a railway line from the Mississippi River to the coast of California. Fremont’s previous expedition had ended in disaster, but now he was ready to try again.

Carvalho, an adventurer, signed up without even consulting his wife. Although he had never been out West, he was keen and enthusiastic. He and his fellow travellers, a melange of Anglos, Mexicans and Indians, set out from Kansas City in the autumn of 1853.

Carvalho turned out photographs of “exquisite beauty,” producing sublime images of Indians and rugged landscape. But with the onset of fierce winter weather, the expedition unravelled and the men on it had to endure unspeakable hardships. Carvalho himself was in terrible shape, close to starvation.

In Utah, Fremont finally decided to wind up the expedition. He and Fremont parted ways, with Carvalho going to Salt Lake City to seek medical assistance. There he met Brigham Young, a Mormon leader.

Carvalho never returned to the West, but he published a book, Incidents of Travel & Adventure in the Far West (1856), and moved to New York City to resume his career as a painter.

Carvalho’s daguerreotypes, which were legally owned by Fremont, were destroyed in a fire in 1881, but fortunately, the photographer Matthew Brady had already photographed them.

Carvalho’s name passed into obscurity after his death, but thanks to Rivo’s first-rate film, his manifold talents as an outdoor photographer are recognized.

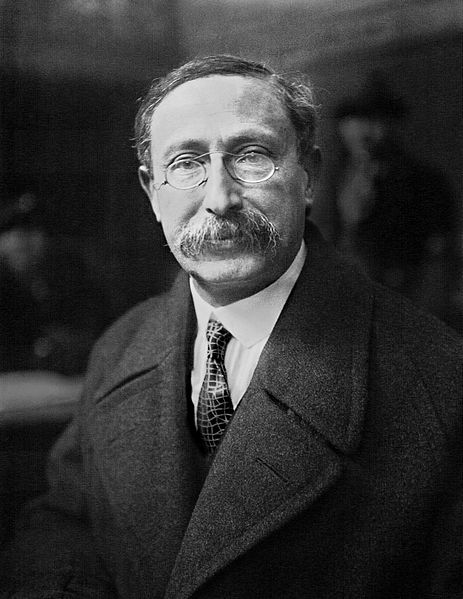

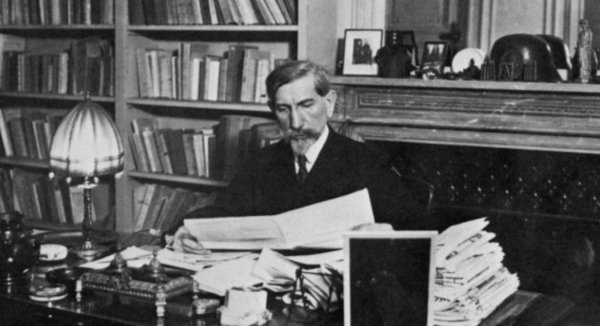

Leon Blum, an Alsatian Jew, was the first Jewish prime minister of France, having twice held that position from the mid 1930s onward. Leon Blum, Loathed and Adored (May 6 and 8), a documentary by Julia Bracher and Hugo Hayat, concentrates on his political career.

A socialist, Blum was a great reformer. Thanks to him, French workers would receive paid vacations, the 40-hour week and collective bargaining rights.

Blum began as a literary critic, but was pushed into politics by the infamous Dreyfus affair. He and socialist leader Jean Jaures formed an enduring bond that culminated with the founding of the newspaper L’Humanite. During World War I, Blum was chief of staff to a government minister.

As leader of the Socialist Party, Blum aroused enmity from the radical right. Charles Maurras, one of its leaders, called for his assassination. “Blum must be killed,” he baldly asserted. In the face of such overt antisemitism, Blum supported the Zionist movement and the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine.

In 1936, Blum was dragged out of his car by fascist hoodlums and beaten up to the chants of “Death to Blum:” and Death to Jews.” A few months later, Blum’s Popular Front coalition — an alliance of socialists and communists — won the general election. He advanced workers’ rights, but due to political pressures, he was unable to rally behind the republicans in the Spanish Civil War.

The Vichy regime arrested him after Germany’s occupation of France in 1940. After being subjected to a botched show trial, he was handed over to the Gestapo in 1943 by the collaborationist French government, headed by Henri Petain. Blum spent the next two years in Buchenwald.

Charles de Gaulle, the post-war French leader, offered him a cabinet post. He declined, but was prevailed upon to represent France in talks to secure a U.S. loan of $600 million.

Blum was an extraordinary figure, and this film serves him well.