Jewish gangsters and homegrown Nazis fought in brawls in the United States in the late 1930s. As Michael Benson writes in his informative book, Gangsters Vs Nazis: How Jewish Mobsters Battled Nazis in Wartime America (Citadel Press), the gangsters were the “good guys.”

Their targets were fascists from the German American Bund and the Silver Legion, both of which supported Nazi Germany and vilified Jews.

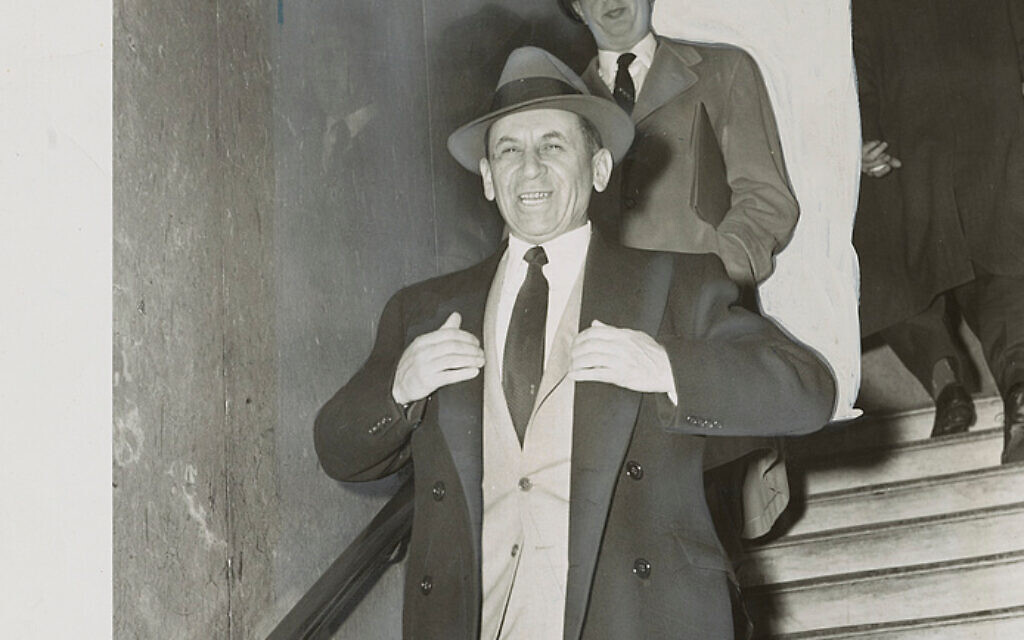

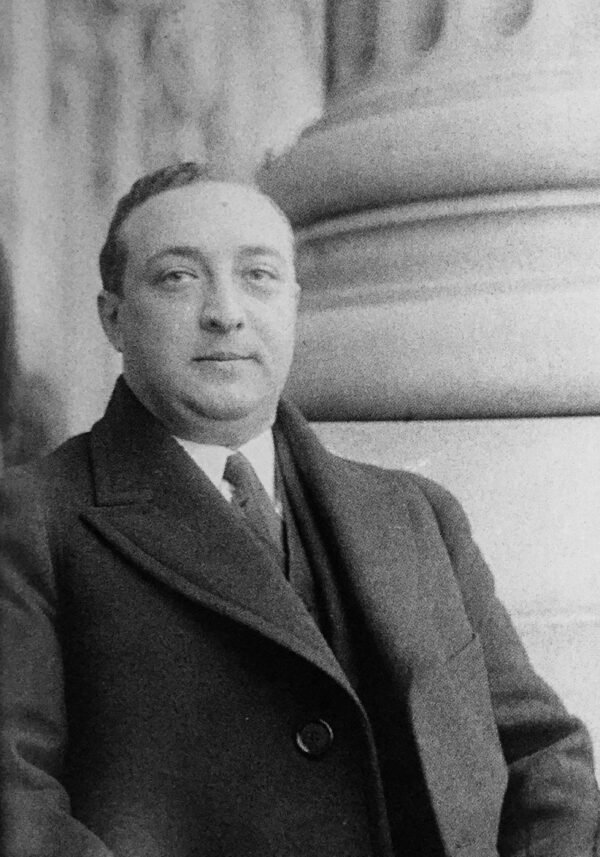

Meyer Lansky, a notorious underworld figure, was a key operative in this campaign. Surprisingly enough, it was conceived by a former U.S. congressman, special sessions judge and chairman of the American Jewish Congress, a Polish Jew named Nathan David Perlman whose family immigrated to the United States in 1891 when he was four years old.

Troubled by the increasing boldness of the Nazis, Perlman contacted Lansky — an immigrant from Eastern Europe — and asked him whether he and his well-armed foot soldiers from Murder, Inc. were prepared to resort to force to curb their antisemitic activities. Perlman had no objection to broken bones, shattered ribs, busted knees or bloody faces, but he carefully drew the line at homicide.

Lansky was only too glad to oblige.

Among the high-profile mobsters he recruited to bash Nazis were Emanuel “Mendy” Weiss, Abraham “Kid Twist” Reles, Martin “Bugsy” Goldstein, Harry Strauss and Charles “Bug” Workman.

Not being familiar with the local Nazi scene, two of Lansky’s recruits approached Judd Teller, a Jewish reporter in New York City, for a list of the “Nazi bastards” who needed to be taught a lesson they would never forget. Having obtained this information, they set out on their secret mission to mug the Nazis, baseball bats, brass knuckles and crowbars in hand.

Benson, a seasoned journalist, tells this little-known story in tabloid-style format. His colloquial language is rough on the edges, but it usually works. Unfortunately, his book is bereft of an index.

The other Jewish figures of interest in his usually entertaining book are the boxer Barney Ross, who socked it to Nazis when the opportunity arose, and Herb Brin, a resident of Chicago who provided anti-Nazi intelligence to the toughs who meted out justice.

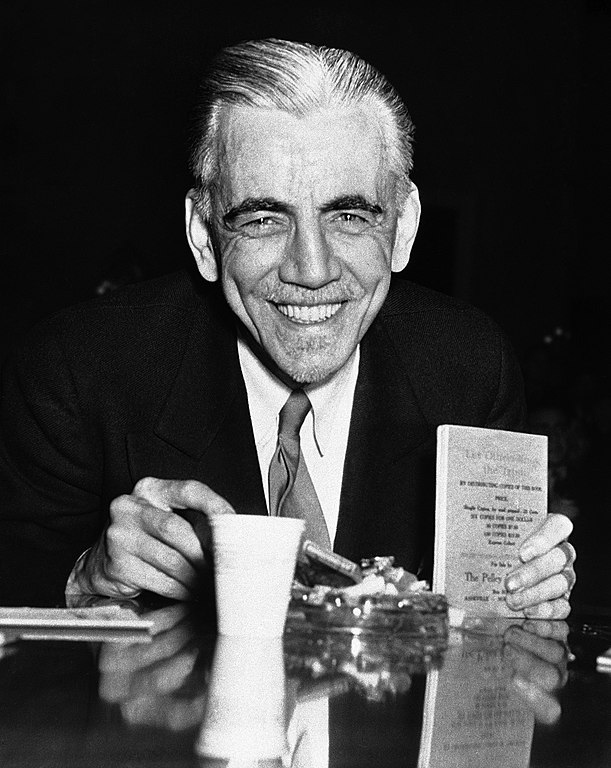

The villains in his narrative are Nazis. Benson focuses on two of their leaders — Fritz Julius Kuhn, the head of the German American Bund, and William Dudley Pelley, the leader of the Silver Legion.

Kuhn, born in Munich in 1896, was a German army infantry officer during World War I. After earning a degree in chemical engineering, he immigrated to the United States in 1928. He was employed by the Ford Motor Company on the assembly line and then worked as an x-ray technician. He became a naturalized citizen in 1934. Two years layer, he assumed the leadership of the German American Bund, which had a membership of 50,000 from coast to coast and represented 0.2 percent of ethnic Germans in the United States.

The German American Bund had its headquarters in Yorkville, a neighborhood in Manhattan. By 1938, New York City had the third largest German-speaking population after Berlin and Vienna.

In April of that year, Lansky, accompanied by 15 gangsters, attacked a German American Bund meeting marking Adolf Hitler’s 49th birthday. The Nazis complained, prompting New York’s half-Jewish mayor, Fiorello LaGuardia, to reach an understanding with Kuhn.

“The mayor told the Nazis okay, we’ll keep the Jews off your back, but with a few caveats,” Benson writes. “The Nazis were forbidden to wear uniforms, display swastikas, sing songs and march to drums. And they had to stick to their own turf in Yorkville.

“The Nazis agreed, and that was supposed to be the end of the gangster campaign of pain. LaGuardia assigned Jewish cops to Yorkville events, so if trouble erupted, the Nazis would be made to feel as uncomfortable as possible.”

This arrangement spelled finis to Lansky’s strong-arm anti-Nazi campaign, says Benson.

In the winter of 1939, however, an unemployed Jewish plumber named Isadore Greenbaum lunged at Kuhn as he delivered a speech at Madison Square Garden, causing pandemonium and resulting in Greenbaum’s arrest.

Outside of New York City, Perlman focused his anti-Nazi efforts in Newark, New Jersey, which was home to 65,000 German Americans and where the novelist Philip Roth and the mayor of New York City, Ed Koch, grew up. In 1938, Perlman reached out to the bootlegger Abner Zwillman, and he wreaked havoc on the Nazis there.

David Berman, the owner of gambling parlors in Minneapolis, dealt with members of the Silver Legion there. Pelley, its chief spokesman, was a journalist, short story writer and screenwriter who sought to herd Jews into special reservations.

The Silver Legion in Cleveland came under pressure from the gangster Morris Barney “Moe” Dalitz, who “made bad things happen to businesses owned and operated by Nazis.”

In Los Angeles, a hotbed of the Silver Legion, Jewish lawyer Leon Lawrence Lewis assembled a squad of spies to combat the Nazi menace. They learned that Nazis were planning to lynch 20 Hollywood personalities like the singer Eddie Cantor and the studio mogul Samuel Goldwyn. Lewis, in vain, tried to persuade the police department to take action. Stepping into the breach, Perlman recruited the gangster Meyer Harris “Mickey” Cohen to take matter into his own hands.

By 1939, two years before the United States declared war on Japan, the American Nazis were, as Benson observes, “in disarray and on the run.”

German American Bund leaders in New York City were charged with filing fraudulent tax returns, and Kuhn was arrested and charged with embezzlement. In 1945, he was deported to Germany, having been declared an “enemy agent” two years earlier. He was then incarcerated under Germany’s de-Nazification laws. In 1940, nine Nazis who had spoken at a rally at a Nazi camp in New Jersey were found guilty of breaking a new “hate” law and sentenced to 12 to 14 months in prison.

Pelley, meanwhile, was investigated by the U.S. Congress. Subsequently, he was arrested over an alleged violation of a suspended sentence concerning a 1935 fraud conviction. After Pearl Harbor, Pelley disbanded the Silver Legion, but continued publishing subversive material in his magazine Roll Call before he was convicted of sedition and imprisoned until 1950.

At the end of the war, U.S. Supreme Court justice Robert Jackson, who had been assigned to prosecute Nazi war criminals at the Nuremberg war crimes trial, appointed Perlman as a consultant. Perlman died in 1952 at the age of 64.

Lansky, having been investigated for tax evasion, fled to Israel in 1970, but was deported to the United States in 1972. Acquitted at a 1974 trial, he spent his final years in Hallandale, Florida, where he died in 1983.

By then, several of his associates had either been executed in federal prisons or murdered by rivals.