The myth persists that Jews do not excel in sports. Why this myth lingers on is beyond understanding. It’s true that Jewish mothers cajole their children to become doctors, lawyers, dentists and accountants rather than baseball or hockey players. But it’s patently untrue that young Jewish men and women are averse to excelling in sports.

On a per capita basis, Jews have acquitted themselves quite honorably in a variety of sports, as Jewish Jocks: An Unorthodox Hall of Fame (Hachette Book Group) indicates. This informative book, edited by Franklin Foer and Marc Tracy, consists of more than two dozen concise essays of varying quality on famous Jewish figures in sports down through the ages.

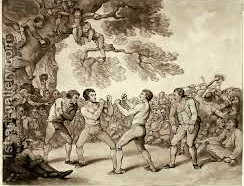

The introductory essay, by Simon Schama, is on the 19th century British boxer Daniel Mendoza (1764-1836), who was popularly known as The Light of Israel. A prize fighter who used his wits as much as his fists, Mendoza was a brawler, the first middle-weight boxer to win a heavy-weight title. He made and lost a fortune and died penniless. So much for the malicious stereotype that Jews are physically weak and financially adept.

Franklin Foer showcases the American pugilist Benny Leonard (1896-1947), who held the light-weight title from 1917 to 1925. Pound for pound, he was one of the finest boxers of all time, in a league with Muhammad Ali and Jack Dempsey. Foer describes him as the first Jewish sports hero of the mass media age.

Novelist Ernest Hemingway had high words of praise for Sidney Franklin (1903-1976). As he put it, “I can tell you truly, all questions of race and nationality aside, that with the cape he is a great and fine artist and no history of bullfighting that is ever written can be complete unless it gives him the space he is entitled to.” Franklin, who transformed himself from a “Brooklyn nebbish” into a “murderous Latin heartthrob,” was a matador par excellence, plying his trade in Latin America. “Instead of selling insurance or filling someone’s teeth,” he famously said, “I fought bulls.”

In Howard Jacobson’s judgment, Marty Reisman (1930-2012) was the finest table tennis player ever produced by the United States. An outstanding showman, he was a thrilling athlete to watch by virtue of the power of his strokes and his ability to bring spectators into the sheer drama of his games.

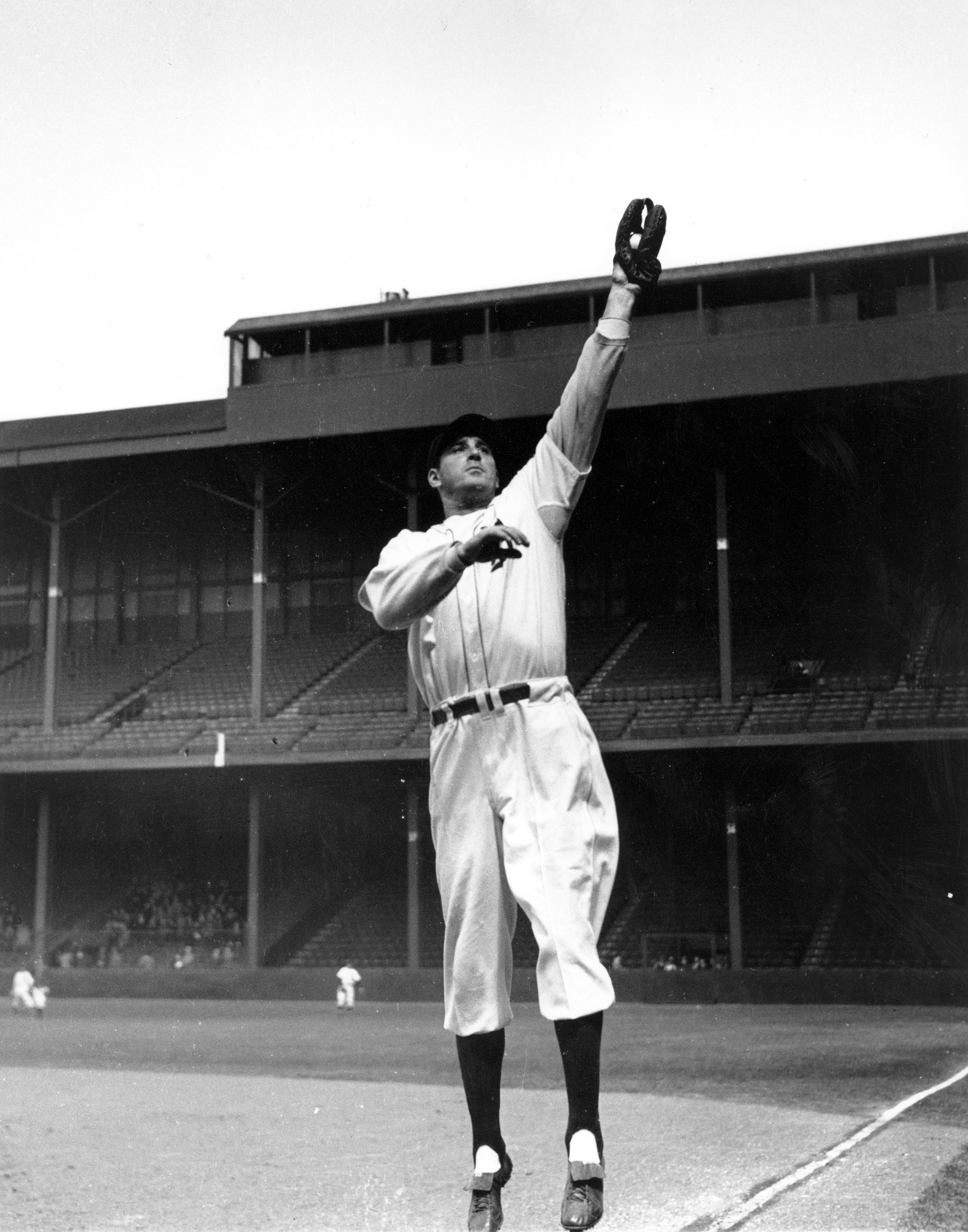

Next to the legendary Babe Ruth, Hank Greenberg (1911-1986) may have been the best player in the annals of baseball, Ira Berkow suggests. His lifetime statistics inspire respect: a .313 batting average, 331 home runs and 1,276 runs batted in. Greenberg, in 1938, hit 58 home runs, almost eclipsing Ruth’s monumental record of 60, which was eventually broken. Nicknamed the Hebrew Hammer, he was, as one sports writer gushed, “the perfect standard bearer for Jews.”

The fencer Helene Mayer (1910-1953) won six German championships and a gold medal at the 1928 summer Olympic Games in Amsterdam. Along with the high jumper Gretel Bergmann and the hockey player Rudi Ball, she was the only token athlete of Jewish descent selected to represent Germany at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. Half-Jewish and half-Christian, Mayer won a silver medal in her main event. As she accepted the medal, Joshua Cohen writes, she gave a Nazi salute, later claiming she was only trying to protect her family in Germany.

During the 1950s, Al Rosen (1924–), the third baseman for the Cleveland Indians, was arguably the “dominant hitter” in baseball. “In his rookie year, he led the American League in homers,” says David Margolick. “For five straight years he batted in 100 or more runs. Four times, he was an All-Star. In 1953, he came within .001 of winning the Triple Crown, and was unanimously voted the Most Valuable Player. Had he not suffered a career-limiting injury in 1954, at the rate he was going he would surely have reached the Hall of Fame.”

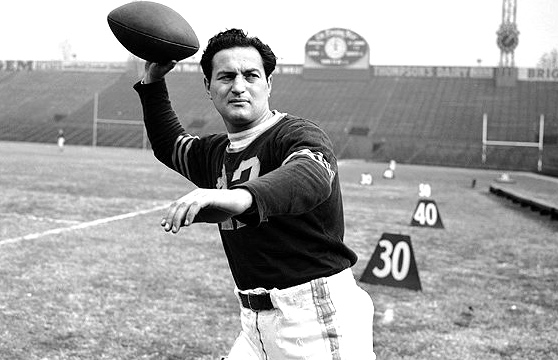

Sid Luckman (1916-1998) was an American football star. Big and rugged, he appeared on the cover of Life magazine after Columbia University, his team, defeated Army in a memorable, snow-bound game. Later, for the Chicago Bears, he threw seven touchdown passes in one game, a record that has never been broken, writes Rich Cohen.

Grigory Novak (1919-1980) was a world-class weightlifter for the Soviet Union and, as David Bezmozgis notes, a refutation of a joke that Jews were lousy in sports. While conducting his research on Novak, he was asked by a Russian-Jewish librarian whether he knew the shortest Soviet joke. He did not. “Jewish athlete,” quipped the librarian. A Ukrainian Jew, Novak was a silver medallist in Helsinki in 1952, the first Olympics in which the Soviet Union participated. But due to an altercation, during which he threw an antisemite down the stairs after being called a zhid, Novak was publicly denounced, stripped of his titles and dropped from the Soviet squad. He was subsequently rehabilitated.

Dolph Schayes (1924 –), in Marc Tracy’s estimation, was the greatest Jewish basketball player. Over 16 seasons with the Syracuse Nationals and the Philadelphia 76ers, he amassed a career average of 18 points and 12 rebounds per game, and was selected for 12 All-Star Games. He coached Wilt Chamberlain and was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Red Auerbach (1917-2006) was probably the greatest basketball coach, leading the Boston Celtics to 16 NBA championships from 1957 to 1986. According to Steven Pinker, his innovations changed the game.

Playing for the Los Angeles Dodgers, Sandy Koufax (1935 –) was the consummate baseball pitcher and no-hit specialist, once declining to pitch the opening game of the 1965 World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur, Jane Leavy recalls.

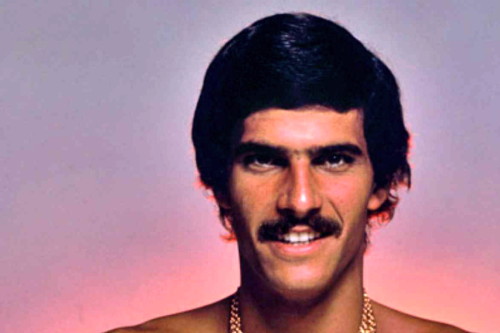

Mark Spitz (1950 –) was quite the swimmer, winning nine Olympic golds, seven at the 1972 Munich Games, and breaking 33 world records. “After Munich, he went commercial in a manner not yet the norm in amateur athletics,” says Judith Shulevitz. “He signed contracts worth $5 million, another world record for an athlete, with the likes of Schick, Adidas and the milk industry. He called himself, bluntly, “a commodity, an endorser.'”

In closing, I’ll mention two of the finest Jewish sports writers of the 20th century, Shirley Povich (1905-1998) and Robert Lipsyte (1938 –), both of whom are included in this book.

Povich, the Washington Post’s sports columnist, was widely respected in the nation’s capital. “It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that every Washingtonian read Povich,” writes Noam Scheiber. “The curse of the sports writer is overwriting. But when Povich aspired to literature, he often achieved it.”

Lipsyte, a New York Times’ sports reporter and columnist, was one of my favorite journalists. As I recall, he was in his prime from the 1960s to the 1980s. Lipsyte possessed a deep admiration for players and coaches, but he always carried a “bullshit detector,” his son, Sam, points out.

And as I can attest, he answered fan letters. In the mid-1960s, he was kind enough to send me a letter, typed on Times letterhead, listing the qualities a journalist needs to succeed in the business. I’ve keep that letter in my archives.