A new and thoughtful documentary about Jewish resistance to Nazi oppression, Resistance: They Fought Back, will be broadcast on the PBS network on Monday, January 27 at 10 p.m. (check local listings). It coincides with International Holocaust Remembrance Day and the 8oth anniversary of the Red Army’s liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the Nazi extermination camp in Poland.

Six million Jews, or one-third of the world’s Jewish population, perished during Nazi Germany’s genocidal campaign from 1939 to 1945. The vast majority of Jews did not and could not resist this murderous onslaught.

The reasons are clear. Jews were unarmed and psychologically unprepared for Adolf Hitler’s diabolical scheme to eradicate the Jewish people of Europe. In short, they could not push back against the immense power of the single strongest European state, which was bent on their destruction.

Nevertheless, a brave and resourceful minority of Jews, steeped in a fighting spirit and armed with a minimum of weapons, resisted ferociously. Still other Jews, who had no access to guns and grenades, fought back by non-violent means.

This is the stirring story told in Resistance. It unfolds, in part, through the medium of vivid vintage photographs and graphic newsreels. Its appeal is enhanced by interviews with the children of survivors and historians such as the late Yehuda Bauer of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Although we will never be able to exactly ascertain how many Jews fought back in the face of the greatest odds, we know that upwards of 30,000 joined partisan bands in western and eastern Europe during World War II. We also know that five of the seven rebellions that broke out in Nazi concentration camps were led by Jewish inmates. And, of course, we are familiar with the doomed but heroic 1943 Warsaw ghetto uprising.

In light of these facts, the late American historian Richard Freund is on safe ground when he asserts early on in the film that Jews “did not go to their deaths as sheep to the slaughter.”

Jews who had not been trained as fighters resisted the Nazis as best they could. In the Warsaw ghetto, they fed the hungry, cared for the sick, established illegal schools and libraries, and, like the historian Emanuel Ringelblum, documented everyday life. By doing so, they defied the Nazis, whose objective was to kill the Jewish body and soul.

In the Lithuanian city of Kaunas (Kovno), a Jewish mother entrusted a child to a Christian foster family, realizing this was its only chance for survival. Looking back, her daughter muses, “I think it was a big act of resistance. It took so much courage to do that.”

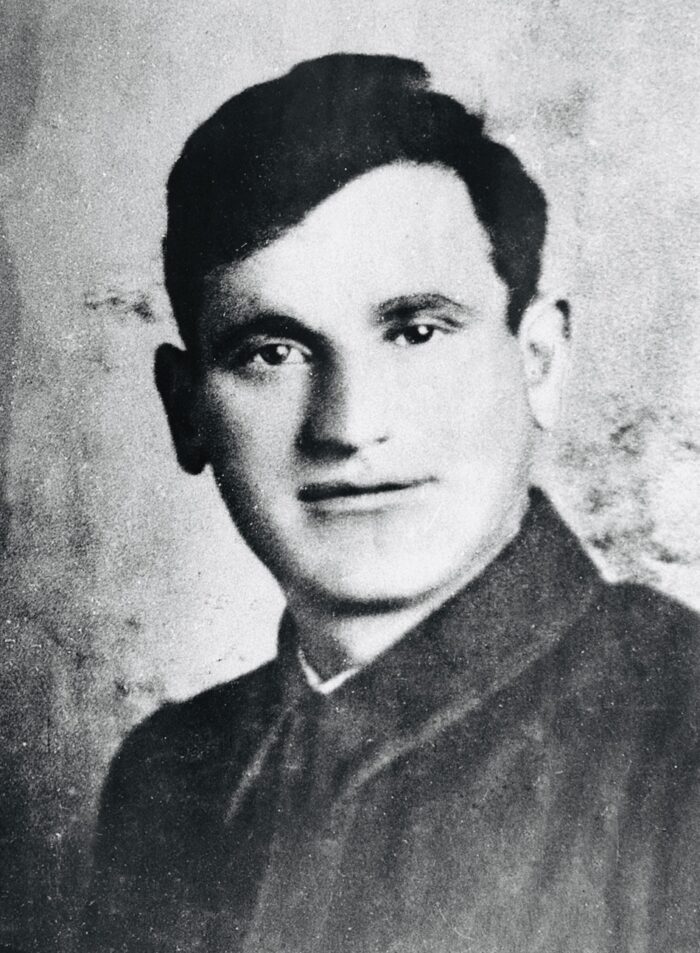

In Vilnius (Vilna), the capital of Lithuania and a center of Jewish learning, the poet Abba Kovner formed a band of partisans, exhorting his fighters to “resist to the last breath.” Kovner’s band, operating from a nearby forest, killed more than 200 German soldiers, bombed troop trains and blew up bridges.

Tuvia Bielski and his brothers established a secret camp in the Naliboki Forest in Poland for Jews fleeing Nazi persecution, a saga recreated by a 2008 Hollywood movie. Their community consisted of, among other amenities, a hospital, classrooms for children, a soap factory, a communal bath and butcher shops. In exchange for arms and food, they provided services to other partisan groups. By one estimate, the Bielskis saved 1,200 people. Regrettably, this intriguing episode is glossed over.

Bela Hazan, a Jewish courier from Poland, is the subject of another profile. Masquerading as a Polish Catholic, she delivered messages and weapons to Jewish ghettos in Grodno and Bialystok. By all accounts, the Nazis created 1,200 ghettos, virtually all of which were located in eastern Europe.

The film references rebellions in two Nazi extermination camps, but fails to examine them in any detail.

The 1943 uprising in Sobibor, led by a captured Soviet Jewish army officer, resulted in the deaths of some German and Ukrainian guards and enabled several hundred Jews to escape into a dense forest. Only fifty of the escapees managed to survive the manhunt mounted by the Germans.

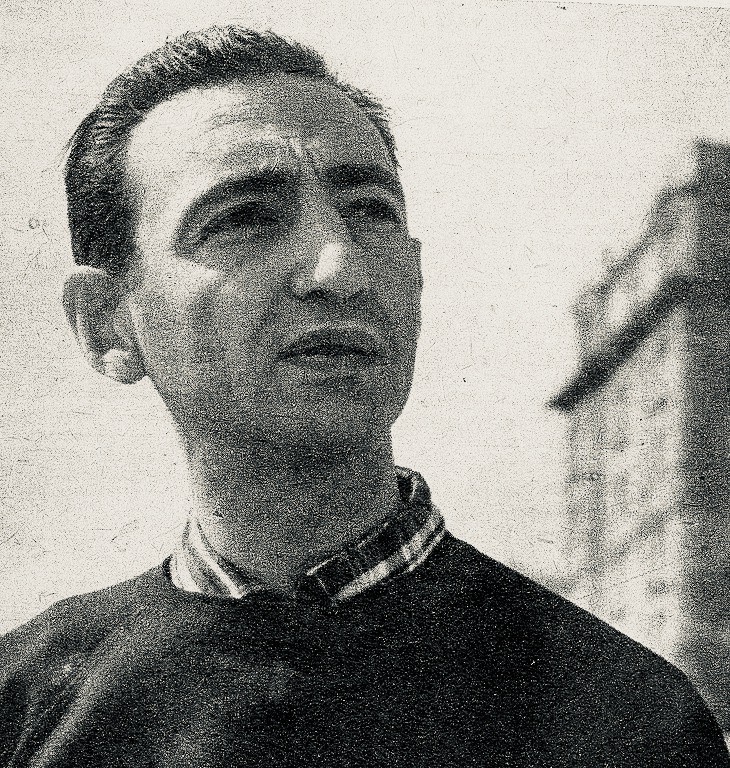

The 1944 revolt in Auschwitz-Birkenau was organized by sonderkommandos, the Jewish men who shepherded Jews into the gas chambers, cleaned up the mess after they had been murdered, and hauled their corpses to the crematoriums. One of these individuals, Marcel Nadjari, a Jew from Greece who had served in the Greek army before its surrender to Germany, compiled notes about his horrific experiences in the camp. He buried them in a bottle that was found in 1980.

The revolt in which he participated was mercilessly crushed by the Germans at a cost of 450 lives, but the rebels managed to destroy a crematorium and a gas chamber before almost all of them were shot.

The Warsaw ghetto uprising, the most important Jewish revolt during the Holocaust, occurred after all but about 60,000 of its inhabitants had been deported to the Treblinka extermination camp. Unfortunately, this oft-recounted episode in Jewish martyrdom is given short shrift, as if it was a minor incident. Voiceovers from one of its commanders, Marek Edelman, add touches of humanity and gravity to the segment.

The film suggests that much is still unknown about the full extent of Jewish resistance in Nazi-occupied Europe. Yet Resistance leaves viewers in no doubt that some Jews fought back with all their might, dispelling the myth that Jews behaved passively as the Nazi menace bore down on them relentlessly.