When Germany entered World War I a century ago this summer, millions of Germans saw them off in a burst of patriotism, assuming that a great victory was imminent.

Swept up by the nationalist fervour, 100,000 German Jewish men joined the ranks of the armed forces. Of these, 80,000 served on the front lines and almost 12,000 fell in battle.

Assumptions that the war might eliminate antisemitic stereotypes and barriers in German society were soon dashed. Antisemitism rose steadily in the first months of the conflict, reaching a crescendo in November 1916, when the German army took a census of its Jewish soldiers in response to numerous reports that Jews were war shirkers.

Tim Grady, a senior lecturer in European history at the University of Chester in Britain, has written an important book about the events surrounding this disconcerting incident, which cast a dark shadow on Germany’s Jewish community of 550,000. The German-Jewish Soldiers of the First World War in History and Memory, published by Liverpool University Press, is one of the first books of its kind in English on this topic.

“Despite the massive growth in memory studies, scholarship has paid very little attention to Germany’s Jewish soldiers who fought and died in the trenches of the First World War,” he writes.

According to Grady, Jewish organizations and individuals lined up behind the war in almost unanimous fashion.

Two days after the war broke out, the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith, which had been formed in 1893 to combat antisemitism and defend the rights of Jews, published a declaration of support in the press stating that “every German Jew is ready to sacrifice property and blood as duty demands.” Shortly afterwards, the Zionist Organization for Germany urged its members “to give yourself … to the fatherland.”

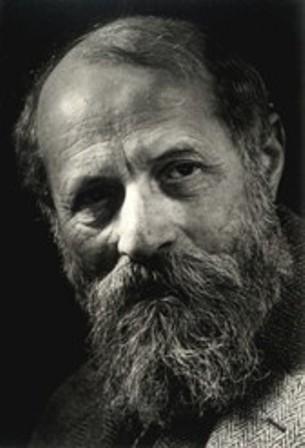

The Jewish-owned publishing houses, Ullstein and Mosse, printed supportive articles in their respective newspapers, while Walther Rathenau, the Jewish industrialist, and Martin Buber, the philosopher, each issued statements in support of the war effort.

Some Jews, like the Zionist Gershom Scholem and the anarchist Gustav Landauer, demurred. But on the whole, German Jews rallied behind the cause. “Love for the Jewish people does not contradict love for the German fatherland,” a member of the Zionist Blue-White organization said after having joined the army.

As hopes for a swift battlefield triumph faded, antisemitism, which had never been far below the surface in Imperial Germany, emerged. Right-wing groups singled out Jews for shirking their soldierly duty at the front, or attacked them as war profiteers and traitors.

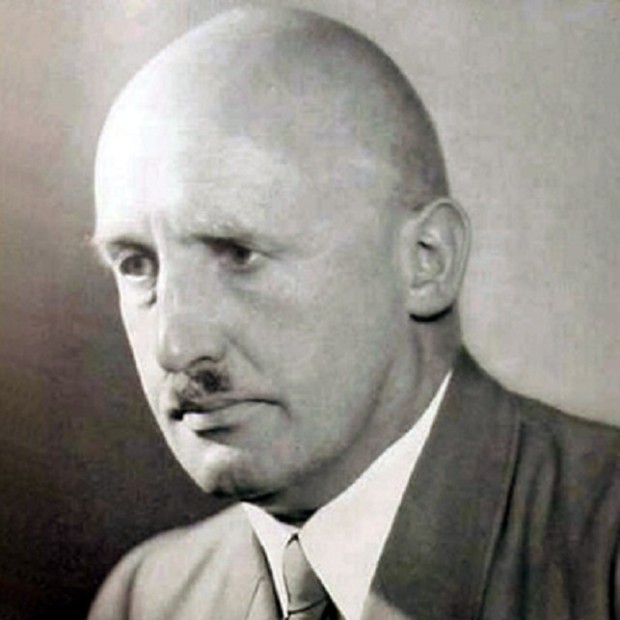

The Prussian war ministry received a stream of letters suggesting that Jews were avoiding front-line military service. These letters were either ignored or answered in very general terms. In October 1916, however, the new Prussian war minister, Adolf Wild von Hohenborn, decided to investigate the accusations. He instructed military commanders to complete a detailed census by Nov. 1.

“As an exercise in statistical analysis, the census was inherently flawed,” Grady writes. “On the day of the count, vast numbers of Jewish soldiers were absent from the front. This was either because they were wounded or on leave, or in some cases because their commanding officer had maneuvered to remove them from the front line.

“Flaws in the war ministry’s data collection process were only a minor issue, particularly as it never actually released the results of the census. Of far greater concern for German Jewry was the fact that the military authorities had acquiesced to the demands of antisemitic groups and issued a census at all.”

Although the war ministry claimed that the census was never intended to harm or offend Jewish military personnel, the issue never died. Germany’s right-wing press frequently dredged it up, calling into question the loyalty of Jews.

By that point, 3,000 Jewish soldiers already had been killed.

After the war, fascists like Hitler raised the issue, blaming Jews and others for the “stab in the back” that culminated in Germany’s surrender in November 1918.

Left-wing Jewish revolutionaries like Rosa Luxemburg and Kurt Eisner were blamed for the defeat. Many of these Jewish figures were murdered by counter-revolutionary forces, but as Grady observes, “the connection between the extreme left and German Jewry proved hard to shake off among the general population.”

Leaflets and pamphlets defaming Jews appeared all over Germany. Alfred Roth, an antisemitic propagandist writing under the pseudonym of Otto Armin, published the “findings” of the war ministry’s census. Claiming that 300 Christian soldiers had died for every Jewish soldier, he concluded that Jews had been unwilling to sacrifice themselves for Germany. “The notion of selfless devotion to the people and the fatherland has no place among them,” he wrote in a reference to Jews.

Responding to Armin, a Jewish writer named Jacob Segall published a book in 1921 in which he refuted his calumnies.

Jews who had fought in the war reacted in different ways. Some turned their backs on their German identity and embraced Zionism. Others renewed their bonds with Judaism. Still others joined Jewish veterans’ clubs. On the institutional level, Jewish communities throughout Germany became deeply involved in remembrance activities in honor of the Jewish war dead.

With the rise of fascism, some veterans’ associations circulated the lie that German Jews had shirked their wartime duty. By the mid-1920s, most right-wing veterans’ groups, such as the Stahlhelm, had adopted an Aryan clause in their constitutions forbidding Jewish membership. Hitler, in Mein Kampf, had written that Jews had avoided the front: “Nearly every clerk was a Jew and nearly every Jew was a clerk.”

Beyond such vile accusations, Jewish remembrance sites were vandalized, while rabidly antisemitic rags like Julius Streicher’s Der Sturmer published the following headline: The Fairy Tale of the Twelve Thousand Fallen Jews.

With Hitler’s accession to power in 1933, the Nazis unveiled the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service. Ostensibly designed to remove Jews, communists and socialists from the civil service, it exempted Jews who had fought at the front or whose fathers or sons had been killed in action.

Paul von Hindenburg, the German president who had appointed Hitler as chancellor, was instrumental in pressuring the Nazis to include that exemption in the legislation. And in that spirit, Jewish war veterans were treated with respect, even by Germans who shared Hitler’s antisemitic views.

Following Hindenburg’s death in 1934, the Nazis acted with much less restraint. In that year, Heinrich Himmler, the future SS commander, wrote an agitated letter to Hitler complaining that German Jews were still members of a Bavarian officers’ association.

In keeping with Himmler’s missive, Jewish war veterans were no longer a protected minority. “As if to confirm this, Jewish ex-servicemen, who had been excluded from the regime’s anti-Jewish legislation in April 1933, were now dismissed from the public service,” writes Grady.

The situation went from bad to worse in 1935 — the year the Nuremberg laws were passed — when the names of Jewish soldiers killed in the war were omitted from a new war memorial in the town of Unna. When a retired army officer protested, Hitler decreed that future war memorials would not include the names of Jews. But in a concession, Hitler allowed Jewish names to stand on most existing war memorials. Jewish war graves, too, were properly maintained.

During Kristallnacht in November 1938, many war memorial plaques bearing the names of Jews were destroyed in fires that consumed scores of buildings. As World War II approached, some prominent war veterans emigrated. From October 1941, all German Jews, including vets and their families, faced deportation to the east.

Even at this genocidal juncture, Grady notes, the Wannsee Conference, which finalized arrangements for the systematic extermination of European Jewry, issued a special exemption. War-disabled Jews and Jews with war decorations would be sent to “old-age ghettos.” One of these ghettos, Theresienstadt, was a way station to Auschwitz-Birkenau. In the Minsk ghetto, German Jews who had been soldiers in the last war were given preferential treatment.

After the Nazis’ defeat, the new government in West Germany ensured that Jewish soldiers who had been killed in World War I would be included in remembrance activity. Further, the names of Jewish soldiers that had been removed from memorials were reinstated.

In 1953, Jewish war vets who had been denied a war pension since the Nazi era were deemed eligible for one.

Two decades later, an air force base in Neuberg an der Donau was renamed after Wilhelm Frankl, decorated a German-Jewish pilot who was killed in battle in 1917. Six months later, the defence ministry rededicated an army barracks in Mannheim in honor of Ludwig Frank, the first and only member of parliament to be killed at the front in World War I.

The defence ministry, in yet another move to come to make amends, launched an exhibition in 1982 on the history of Jews in the German armed forces.

Justice had finally prevailed.