The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 was a defining moment in the leadup to World War II. Pitting two diametrically opposed ideologies against each other, the three-year conflict was ostensibly a struggle between the left-of-center Republicans and the right-wing Nationalists. On a broader level, it was effectively a proxy war between the fascism of Nazi Germany and Italy and the communism of the Soviet Union.

Two months after the fighting erupted, the Moscow-based Communist International — the Comintern — created the International Brigades, an army of volunteers who supported the Popular Front government, which had been challenged by the forces of Francisco Franco, who, following his victory in 1939, ruled Spain for almost the next 40 years.

Over the course of the war, about 35,000 volunteers from more than 50 countries joined the International Brigades. Upwards of 4,000 were Jewish.

One of these volunteers, Albert Prago, would write, “The International Brigades became the vehicle through which Jews could offer the first organized armed resistance to European fascism.”

True enough.

This aspect of the war is the subject of Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War, a workmanlike book published by Bloomsbury and written by Gerben Zaagsma, a senior researcher and head of the Research Area Digital History and Historiography at the Center for Contemporary and Digital History at the University of Luxembourg.

As Zaagsma suggests, the Jews who rallied to the Republican cause had reason to despise the Nationalists. During the earliest days of the war, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported, the Nationalists issued a proclamation threatening to expel Jews in Spain once they had defeated the Republicans.

Zaagsma cites the comments of one of its commanders, Quiepo de Llano, who, in a radio broadcast, described the war as as “war for Western civilization against the Jews.”

Yet, as Zaagsma acknowledges, antisemitism was not one of the Nationalists’ central tenets. “Systematic persecution of the relatively few Jews under Nationalist control did not take place and a coherent antisemitic policy never developed, neither in the Nationalist zone in Spain nor in Spanish Morocco.”

From the very outset, foreign volunteers flocked to the Republican side. Some were political exiles who had been living in Spain. Still others were athletes who had been due to participate in the People’s Olympiad in Barcelona, which had been organized as a counter-weight to the official Olympic Games in Berlin.

Most the volunteers were recruited by the Comintern, which regarded the International Brigades as an important propaganda tool to promote its Popular Front tactic, which was adopted in 1935.

The Jewish volunteers were a mixed lot.

While Eastern European volunteers tended to be intensely Jewish, many from Western Europe and Canada were internationalists, humanists and communists who did not indentify overtly as Jews. Zaagsma adds that Jewish volunteers from Palestine were criticized for choosing to defend Madrid rather than Hanita, a kibbutz in the Galilee besieged by Palestinian Arabs.

The majority of East European Jewish volunteers were absorbed into the Palafox Battalion of the 13th Polish Dombrowski Brigade, which was renamed the Naftali Botwin Company in 1937 in honor of a young Polish-Jewish communist who had been executed by the Polish government in Lwow on August 6, 1925. Born in Lemberg in 1905, Botwin was a craftsman who was briefly involved with the Jewish socialist Bund before joining the communist youth organization in 1923 and the party itself in 1924.

Two months after its creation, the company was virtually wiped out during an offensive.

The last foreign volunteer to die on the battlefield was Chaskel Honigstein, a Polish Jew who was killed in October 1938. He was given a state funeral.

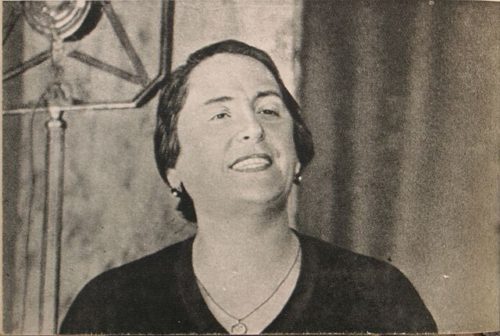

By late 1937, Spaniards had overtaken the number of foreign volunteers in the International Brigades. About a year later, the Popular Front government announced its intention to withdraw the foreigners from active duty. The legendary Dolores Ibarruri, better known as La Pasionaria, hailed their contribution. “You can go with pride,” she said. “You are history.”

Some of the volunteers, particularly those from Germany, were unable to return. Several were ultimately deported to Nazi concentration camps in Poland.

In his final chapters, Zaagsma discusses the fate of volunteers during the postwar era. When the Polish communist regime unleashed an antisemitic campaign in the wake of the 1967 Six Day War, Jewish veterans of the International Brigades were forced to leave Poland. They immigrated to Israel, Sweden and France.

Although volunteers in Israel were not always treated with the respect they deserved, Israeli President Chaim Herzog honored their contributions at a ceremony in 1986 on the 50th anniversary of the Spanish Civil War.