Measured against centuries of recorded human history, the concept of human rights is quite new, having emerged only after World War II as a response to the unimaginable horrors of the Holocaust.

Within two years of these unprecedented atrocities, the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Genocide Convention, which were both intended to protect humanity through international law.

But as James Loeffler contends in Rooted Cosmopolitans: Jews and Human Rights in the Twentieth Century (Yale University Press), the true origins of human rights can be traced back even further in time.

“Much of what we think of today as post-World War II international human rights began life as a specifically Jewish pursuit of minority rights in the ravaged borderlands of post- World War I Eastern Europe,” writes Loeffler, a professor of history and Jewish studies at the University of Virginia.

He fleshes out this theme by focusing on several remarkable Jewish men whose ideas reshaped the legal landscape and who coined such now-common phrases as “crimes against humanity” and “prisoners of conscience.”

They include figures ranging from Peter Solomon Benenson, the founder of Amnesty International, to Hersch Avi Lauterpacht, who drafted an early version of the International Bill of Human Rights.

Benenson was the scion of an Anglo-Jewish family split between London and Jerusalem. His Russian grandfather made a fortune in the oil, sugar and gold mining industries before founding the Anglo-Russian Bank, a key facilitator of trade between Russia and Britain.

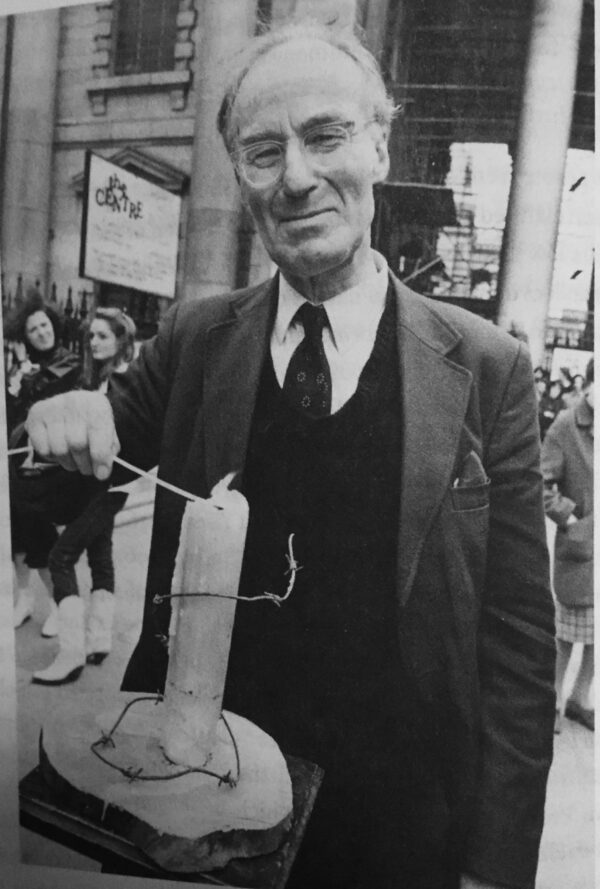

A convert to Christianity, Benenson was an original thinker. As Loeffler puts it, “Amnesty marked a radical new chapter in the history of human rights. Instead of another passel of laws or a clever diplomatic gambit, Benenson proposed a global grassroots movement based only on the power of public opinion.”

Using mass media, celebrity endorsements and public lobbying in his campaigns, he preached the gospel of human rights as “unalloyed universalism.” In the process, he reinvented human rights activism.

Benenson’s iconoclasm extended to Zionism. Although his family was supportive of it, he deplored the manner in which the Arab-Jewish struggle in Palestine turned progressive-minded Jews into nationalistic zealots.

Lauterpacht, born in what is now Ukraine, worked with American Jewish community leaders to ensure that Jews in newly independent Poland would achieve equal rights in the wake of World War I. They convinced the United States, Britain and France that Polish statehood and civic rights for Poland’s Jewish, German and Ukrainian minorities should be inextricably linked.

On June 28, 1919, Polish President Ignacy Paderewski signed the first of the Minorities Treaty, a template for similar agreements with the new states of Albania, Austria, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Iraq, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Turkey and Yugoslavia.

Much to Lauterpacht’s disappointment, the treaty was flouted by Poland, one-third of whose citizens were not ethnic Poles. Pogroms erupted, while certain right-wing Polish politicians, namely Roman Dmowski, were intent on forging an ethnically homogeneous state. In response, Lauterpacht launched public relations campaigns to force Poland to honor its commitments.

Nearly three decades later, at the Nuremberg war crimes trial, he teamed up with U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson to introduce the idea of “crimes against humanity” into the legal lexicon.

Jacob Robinson, a Jewish lawyer and member of Lithuania’s parliament, was a champion of minority rights. From 1922 to 1926, he led the Minorities Bloc in the Sejm, representing the interests of Jews and ethnic Poles and Germans.

Following the Soviet invasion of Lithuania in 1940, Robinson and his family fled, reaching the United States via Romania, Yugoslavia, Italy and Vichy France.

Working collaboratively with the American Jewish Congress and the World Jewish Congress out of an office in New York City, he devised the concept of “human rights.” The phrase crept into the modern diplomatic idiom and steadily gained currency in Anglo-American diplomacy, supplanting the discredited “minority rights” ideal.

At the Nuremberg trial, Robinson was in charge of preparing the charge sheet against the 24 highest-ranking Nazi war criminals and redrafting several indictments.

Jacob Blaustein moved in two separate worlds.

As president of the American Jewish Committee, he said, “The rights of Jews will only be secure when the rights of people of all faiths are equally secure.”

And as the owner of the American Oil Company, he set new standards. Among his innovations were the first high-octane motor fuel for cars, the first metered gasoline pump, and the first drive-through filling station.

In Loeffler’s view, Blaustein was instrumental in inserting human rights as a key element of U.S. foreign policy. Blaustein’s interlocutor at the U.S. State Department, Isaiah Bowman, was an “aggressive antisemite” who had been the president of Johns Hopkins University until the spring of 1945.

Ignoring Bowman’s prejudices, Blaustein urged him to view human rights not as a concession to minority privileges, but as “a practical way to defeat Soviet talk of group rights for national minorities. The argument resonated.”

Turning to a related topic, Loeffler notes that the rapid rise of human rights into global consciousness coincided with the growing demonization of Israel in the new human rights culture. With its victory in the Six Day War and its occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, human rights activists began to see Israel in a different light.

This shift manifested itself at the United Nations when the General Assembly officially branded Zionism as a form of racism. That resolution was eventually rescinded, but as Loeffler says, “Jewish human rights activism never fully recovered from that crisis.”