The historical relationship between Jews and other Canadians, particularly with French Canadians, is not merely fundamentally important, it is also quite controversial. Phyllis Senese wrote in 1977 that “the history of antisemitism in Quebec remains to be written” and that, further, “a great deal of superficial and shallow writing on antisemitism in Quebec is in print.”

She is still basically right on both counts

Analyses of antisemitism in Quebec vary widely. At one extreme, there is Denis Vaugeois who, in his recent volume on the Hart family of Trois Rivières, takes issue with a statement of historian Jacob Marcus that Aaron Hart had encountered “a great deal of anti-Jewish sentiment.”

“Where did he find this ‘anti-Jewish sentiment?” Vaugeois writes. “I searched long and hard for it, in vain. And that, in fact, was the reality of ‘Canadian’ Jews: there was not an ounce of anti-Jewish sentiment around them … Rather than ‘anti-Jewish sentiment,’all doors were open to Jews…”

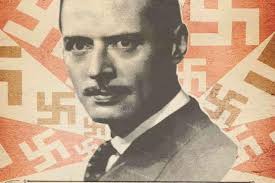

At the other extreme, one finds affirmations that a pronounced antisemitic current of thought existed in Quebec, embodied, according to Esther Delisle, in prominent personalities like the Quebec nationalist historian Lionel Groulx, and in the Montreal francophone daily, le Devoir, and not merely in radical antisemites like Adrien Arcand.

Moreover, antisemitism in Quebec is one of the few issues in Canadian Jewish history that has become a major subject for public controversy, debated not merely in scholarly journals but in the op-ed pages of the Quebec daily press in both French and English. If for no other reason, the subject deserves our close attention.

What follows cannot pretend to be a comprehensive look at antisemitism in Quebec. I will, rather, devote this article to some reflections on the beginnings of the relationship between Jews and other Canadians in the pre-confederation era, understanding that most of the relatively few Jews in Canada in this period resided in what we now think of as Quebec.

Any analysis begins with the fact that Jews in 18th century Canada were British subjects. This meant that there was no legal basis for discriminating against them as Jews with respect to their pursuit of a livelihood. It meant as well that they were English speaking and accustomed to British ways.

They were, therefore, a generally good “fit” in British North America and constituted a significant proportion of Quebec’s small English mercantile community in the 18th century. Because the English community was so small, Jewish mercantile newcomers enjoyed a relatively good reception, as in many other British colonies of this period.

If Jewish merchants were resented, then, it is most likely that they were not primarily resented as Jews but by English Canadians as competitors, and by French Canadians as part of a British mercantile class that had aggressively displaced French Canadian merchants through superior political and trade connections.

They would thus have been largely assimilated by French Canadians of that era into their resentment of the British “other.” It is quite likely that negative Christian attitudes toward Jews, the heritage of both Protestants and Catholics in Canada, may have occasionally come to the surface, though historian Gerald Tulchinsky finds relatively little evidence of this.

There was, however, one area —political life — in which Jews in Canada were subject to societal prejudice as Jews. Western European nations, like France and England, self-consciously referred to themselves as “Christian.”

In early modern times, some Christian countries tolerated Jews and gave them a greater or lesser degree of social, religious and economic freedom. In none of them, however, was it understood that toleration gave Jews rights in the political arena.

On the contrary, it was generally assumed that Jews constituted a separate “nation” that had no inherent political rights in the country in which they actually lived. Jews exercising equal political as well as economic rights was literally a revolutionary idea, and even in the atmosphere of revolutionary France, the accession of Jews to equal civil and political rights happened only after a lengthy and divisive debate.

In England, as was already said, native born Jews were British subjects possessing all the rights and privileges of any native-born English people, “excepting so far as positive enactments of the law deprived them of those rights, immunities and privileges.”

These “positive enactments of the law” included nearly the entire political arena, which was reserved for members of the Church of England. Dissenting Protestants, Catholics, and Jews were therefore included in the economic and social life of England and excluded from its political life.

In many of the British North American and Caribbean colonies during this era, non-Anglican Christians and Jews were likewise excluded from political participation. In others, however, changes were instituted reflecting the makeup of the white population.

The colony of Maryland, for instance, was founded as a refuge for Catholics and hence did not disenfranchise Catholics. In the case of Jews, only the colony of New York consistently allowed them the right to vote, though even there not without challenge.

What of the British colony of Quebec?

It was governed by the Quebec Act, enacted in 1774, which gave Catholics, along with Protestants, quality of political rights, and was silent with respect to Jews. Despite this silence, it is noteworthy that a number of the colony’s Jews were signatories of petitions to the Crown asking for a legislative assembly and other reforms. These Jews were, in effect, acting as though they had the same political rights as their Christian counterparts. Their assumption was to be the subject of a significant challenge in the early 19th century.

The key challenge to Jewish rights in British North America happened when Ezekiel Hart submitted his name as a candidate for the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada in 1807.

His brother, Moses, had previously been warned by their father, Aaron Hart: “I should be glad if you were elected a Member of the House … But what I do not like is that you will be opposed as a Jew. You may go to law, but be assured; you will never find a jury to favour you or a party in the House to stand up for you.”

Hart was elected but could not take his seat because he could not properly take the required oath “on the true faith of a Christian.” The contemporary political debate on this issue, which was of a virulent and partisan nature, included the following relative to Hart’s ability, as a Jew, to represent his constituency:

“[T]he Jews are everywhere a people apart from the body of the nation in which they live … a Jew never joins any other nation. He makes it a religious duty, a consistent rule of conduct, to keep separate from other people … By what right can a Jew be entrusted with the care of the interests of an entire people when he thinks only of himself and of his sect?”

The result of the Hart affair was that professing Jews as such were barred from the legislature. This meant that in Lower Canada, in principle, Jews were now second class citizens, ineligible for membership in the Assembly, and legally unfit to hold other offices which required a formal oath. On the other hand, as Tulchinsky also points out, “[e]xcept for the Assembly, the ban does not seem to have been enforced.”

Meanwhile, in Cornwall, John Elmsley, the chief justice of Upper Canada, had reported an opinion that “Jews cannot hold land in this province”, a ruling that was not overturned until 1803. Benjamin Hart, applying in 1812 for a militia commission, was told that “Christian soldiers would not tolerate a Jew in their midst,” though other Jews did obtain such commissions.

The legal bar against Jews holding office was ended in 1832 by the adoption by the Legislative Assembly of “an Act to declare persons professing the Jewish religion entitled to all the rights and privileges of the other subjects of His Majesty in this Province.”

This legislation stemmed from an 1830 attempt to appoint Samuel Becancour Hart, Ezekiel’s son, as magistrate. The attorney general’s opinion that Hart, as a Jew, could not take the requisite oath led to a petition to the government that resulted in the Act of 1832, which can be seen as similar to other legislation of the period to designed to enfranchise Jews politically in Maryland (1826) and Jamaica (1831).

Significantly, this legislation was adopted with apparently little public controversy. A similar question, which arose over the election of Selim Franklin as a member of the British Columbia Assembly, was also fairly quickly settled by legislation with almost no publicly broadcast anti-Jewish opinion.

Anti- Jewish opinion was not absent in the aftermath of the failed rebellions of 1837, in a manifesto of the “Hunters’ Lodges (Frères Chasseurs) that called for “the strangling of all Jews and the confiscation of their property.”

Dr. Aaron Hart David confided to his diary that his move in 1840 from Montreal to Trois Rivières was occasioned by the “aversion to our religion” in Montreal, which made it impossible for him to establish a medical practice.

Nevertheless, Jews and Judaism failed to become an overt political issue in an ongoing way in early and mid-nineteenth century Canada.

This situation maybe explained by the Jews’ small numbers. In 1831, the first official Canadian census found a mere 107 Jews to be resident of Upper and Lower Canada. This number rises only moderately to 154 in 1841, 451 in 1851, and 1,186 in 1861.

As a rule, those relatively few Jews who did live in British North America were well acculturated into the Anglo-Canadian community.

This does not mean, however, that anti-Jewish prejudice was absent from the Canadas. Stories and references to Jews were present in early French Canadian literature.

Historian Richard Menkis has further observed that many Catholic publications distributed in Canada contained fairly standard anti-Jewish remarks consistent with Catholic teachings on the Jews, and that Protestant merchants, in letters preserved by the R.G. Dun credit-rating company, sometimes expressed their belief that Jewish businessmen “are secretive and deceptive, practising a dubious morality in their dealings with non-Jews”.

Nonetheless, as Gerald Tulchinsky remarks, “non-Jews did business with Jews despite the existence —possibly even the prevalence — of attitudes that held Jews in contempt, fear, and mistrust.”

To the extent that Jews were prominently involved in the political life of their community, they opened themselves up to their political opponents’ using the term “Jew” in denigrating them.

Thus, George Benjamin, editor of the Belleville, Ontario Intelligencer was lampooned by Dr. John Edward Barker, editor of the rival Kingston British Whig in February, 1834 as “the Belleville Jew” who was killed by eating pork.

That same newspaper, four years later, objected to Benjamin’s militia captaincy on the same grounds. Clearly, however, this did not impede Benjamin’s election to the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada in 1857.

On the other hand, Jews were apparently wary in their relations with the majority. When, in 1858, an Italian Jewish child, Edgar Mortara, was taken from his parents on the grounds of his alleged baptism, there was great world-wide protest in many Jewish communities.

Significantly, a leader of the Jewish community in Montreal was reported as having stated at a protest in New York that Montreal Jews hesitated at speaking out in their home town because “those with whom we are in daily intercourse … are subject to the Church of Rome.

Nonetheless, historians of the Jewish community in Canada tend to agree with historian Irving Abella that, “[i]f there was a golden age of Canadian Jewry, one could make a strong case for the period before Confederation, particularly the 1830s and 1840s.”

It would take two major historical trends in the later 19th century to alter this situation: major non-British immigration to Canada and the spread of racist antisemitism from Europe to North America.

Ira Robinson is professor of Judaic studies at Concordia University in Montreal and president of the Canadian Society for Jewish studies.