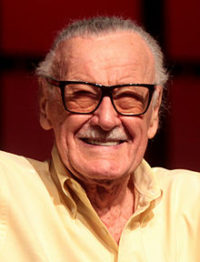

The death of Stan Lee at the age of 95 on November 12 reminds us of the outsized role of American Jews in the development of low to middlebrow cultural industries such as comic books and Hollywood films in the 20th century.

Born Stanley Martin Lieber in 1922 in New York City, the son of Jewish immigrants, Lee would go on to create such superheroes as Spider-Man, the Incredible Hulk and the X-Men.

This was an emerging mass market, but one that required little in the way of capital to get started. Considered somewhat crass, it was looked down upon by more established ethnic groups and hence was one Jewish artists and writers could enter without having to worry about antisemitism.

In 1939, Lee was brought in by a relative, Martin Goodman, to a small comic books publisher. It would eventually become Marvel, and Lee and artist Jack Kirby (born Jacob Kurtzberg) would go on to build a mega-million-dollar empire.

By the mid-1930s, others had already created the modern comic book. An unemployed Jewish novelty salesman named Maxwell Charles Gaines (née Max Ginzberg) decided to put the comic strips published in newspapers between covers and sell them as separate items, thus creating the American comic book.

It was in the midst of the Great Depression, and young Jewish writers and illustrators found themselves without jobs. They faced antisemitic quotas in established fields, so, like the Jews who “invented” Hollywood, created their own industry.

Arie Kaplan, who wrote From Krakow to Krypton: Jews and Comic Books, noted that in contrast to the advertising industry, the comic book industry was free of antisemitism since many of the publishers were Jews, and no expensive academic degrees were required.

The most enduring of all superheroes, Superman, was also the creation of two young Jews, writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster.

In 1938, Detective Comics (later DC), a Jewish enterprise owned by Harry Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz, both born in eastern Europe, published Superman’s first entry in the pages of Action Comics #1. Superman was an instant hit. The so-called “Golden Age” of comics had begun.

Between 1939 and 1941 Detective Comics introduced popular superheroes such as Batman, Wonder Woman, the Flash, and Green Lantern. Marvel Comics had best-selling titles featuring the Human Torch and Captain America.

Was this a genre that somehow drew on the experiences of Jews living as somewhat marginalized figures in a larger society where they often faced antisemitism and locked doors when seeking work?

Most of the superheroes had secret double identities, with mild-mannered alter egos. This, too, might have been reflected the Jewishness of their creators.

They lived in a non-Jewish, somewhat hostile, world. They felt they could succeed in America only if they disguised their identities as Jews. So they tried to assimilate, as best they could, while clandestinely remaining part of their Jewish milieu.

This is a theme taken up by Danny Fingeroth, a former editor at Marvel Comics, in his book Disguised as Clark Kent: Jews, Comics and the Creation of the Superhero. “One might speak Yiddish at home, but that was the language of your embarrassing immigrant parents and grandparents. You speak English in public so you can fit in with your friends at school.”

Fingeroth also sees the superhero-as-savior stemming from Jewish history. “I think the idea of a being who wields great power wisely and justly would be very appealing to people whose history involves frequently being the victim of power wielded brutally and unjustly.”

Kaplan concurs. “Superman actualized the adolescent power fantasies of its creators — two Jewish Depression kids craving a muscle-bound redeemer to liberate them from the social and economic impoverishment of their lives.”

Lee himself wondered whether “there was something in our background, in our culture, that brought us together in the comic book field?

“When we created stories about idealized superheroes, were we subconsciously trying to identify with characters who were the opposite of the Jewish stereotypes that hate propaganda had tried to instill in people’s minds?” Lee’s superheroes were all “outsiders” in one way or another.

After World War II, the comic book industry hit a setback when the U.S. Senate decided to investigate the problem of juvenile delinquency.

The publication of Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent in 1954 claimed that comics sparked illegal behavior among minors, and comic book publishers were subpoenaed to testify in public hearings. A moral panic followed, and the industry removed many of its crime and horror lists.

The superheroes, though, remained standing.

Henry Srebrnik, who owns a collection of pre-1954 comic books, is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.