The majority of Arabs regard Jews as enemies because much of the scholarship about pre-1948 Muslim-Jewish relations is refracted through the lens of the Arab-Israeli conflict, says an American scholar who specializes in the topic.

Typically, such Arabs have never met a Jew, nor can they imagine a time when Jews were an indigenous and integral part of Arab societies, historian Daniel Schroeter said in a speech at the University of Toronto’s Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies on November 21.

Schroeter, a member of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Jewish Studies, spoke about the nature of Arab-Jewish coexistence before the advent of Israeli statehood.

Approximately one million Jews lived in the Middle East on the eve of Israel’s establishment, with three-quarters residing in Arab countries ranging from Egypt to Iraq. In some cases, Jews arrived there before the founding of Islam.

Until the 19th century, Jews, like Christians, were protected minorities, or dhimmis. Although they did not enjoy the same legal status as Muslims and were sometimes persecuted and subjected to violence, they were free to practise their religion and guaranteed a good deal of communal autonomy, he noted.

Schroeter maintained that Jews were not second-class citizens because the concept of citizenship did not yet exist. But Jews and Muslims were keenly aware of the boundaries that set them apart, however porous they may have been.

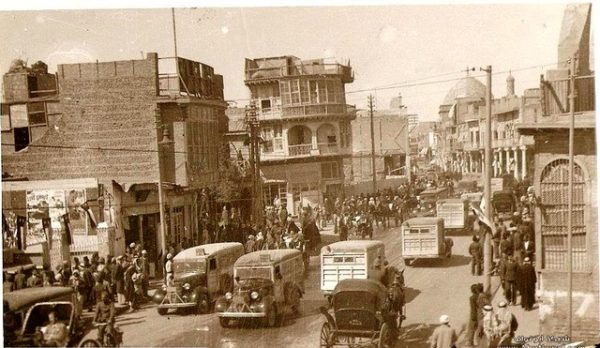

Jews and Muslims often mingled freely at markets, bath houses and coffee shops and shared the same culture because they both spoke Arabic, he said. And as the owners of shops, banks and factories, Jews also interacted with Muslims.

In Morocco, Jewish peddlers hawking their wares were a fairly common sight in rural areas, said Schroeter, an expert on Moroccan Jews.

According to Schroeter, the status of Jews in Ottoman-controlled lands changed significantly when the Ottoman sultan introduced “tanzimat” reforms in 1839 to modernize the empire and secure its territorial integrity against encroaching foreign powers and local nationalist groups.

This reform era, lasting until 1876, sought to integrate non-Muslims into Ottoman society by enhancing their civil liberties and granting them civic equality. As a result, Jews gradually shed their dhimmi status.

By then, external powers like Britain and France had begun to court and protect Jews and Christians so as to extend their influence in the empire. This development caused tension between Muslims and Jews, he said.

The decision by Jews in Morocco and Tunisia to use French rather than Arabic as their working language and to adopt French citizenship over Moroccan and Tunisian citizenship alienated Muslims as well.

In Egypt, a British colony after the 1880s, only one-quarter of Jews obtained Egyptian citizenship.

Citing Iraq as a unique case in the annals of Arab-Jewish relations during the inter-war period of the 20th century, Schroeter pointed out that most Jews there identified as Arabs and possessed Iraqi citizenship. And only in Iraq was Arabic a mandatory language in Jewish schools.

Such was the ambience of the times that Faisal, the king of Iraq until 1933, proclaimed Jews, Christians and Muslims as equal citizens.

Being deeply attached to Iraq, growing numbers of Iraqi Jews joined the Communist Party and supported Arab nationalist political parties. Some Jews were drawn to the Zionist movement, too.

Jews were active in cultural pursuits, participating in the Arabic literary renaissance and playing a role in the Arab musical scene. Two such musicians were Salah and Daud al-Kuwayti.

There were few signs in the 1930s that Jews would be pressured to leave the Arab world, but the 1941 pogrom in Baghdad, which took place during a pro-Nazi coup, may have been one of them.

In contrast to the integrative spirit displayed by the Jewish community of Iraq, the Jews of Algeria were detached from their Muslims neighbors, said Schroeter.

They were citizens of France, spoke French and were educated in French schools. Nonetheless, some Algerian Jews, like the prominent musician Cheik Raymond Leyris, were Algerian to the core. But he was assassinated, raising troubling questions whether Muslims had accepted him as one of their own.