Judy Rakowsky, an American journalist of Polish-Jewish descent, visited Poland in a succession of trips from 1991 onward in an effort to solve an enduring mystery on behalf of her older cousin, Sam Rakowsky.

The issue at hand was the fate of his 16-year-old relative, Hena Rozenek, who vanished after her parents, sisters and brother were murdered in Poland while in hiding from the Nazis.

The Rozeneks were residents of Kazimierza Wielka, a town 45 kilometers north of Krakow. With the Germans bearing down on Jews and consigning them to Belzec, the nearest Nazi extermination camp, they escaped and found refuge in the homes of nearby righteous Polish farmers, who risked their lives to shelter them.

For 18 months, from 1942 onward, they managed to survive, along with the Dulas, another Jewish family. But in 1944, with the end of World War II approaching, antisemitic Polish partisans flushed them out to the shouts of “Give up your Jews! We know you have Jews. Hand them over!”

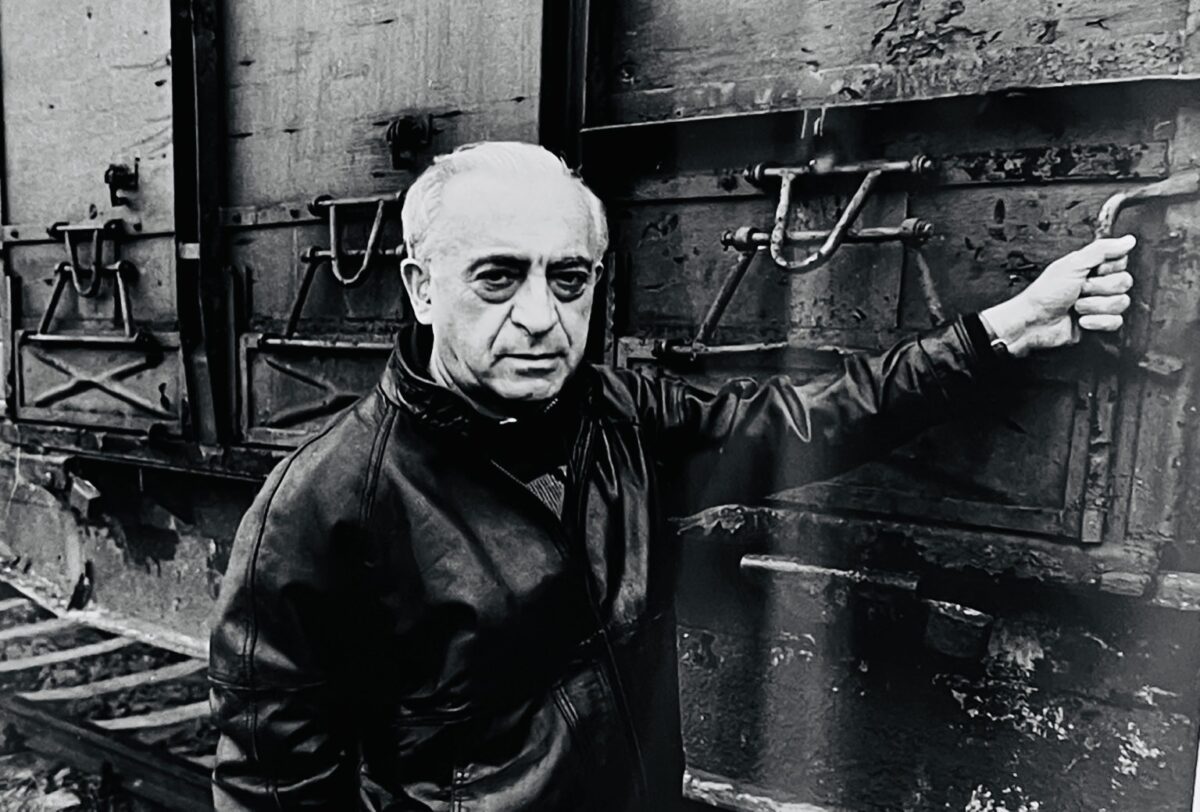

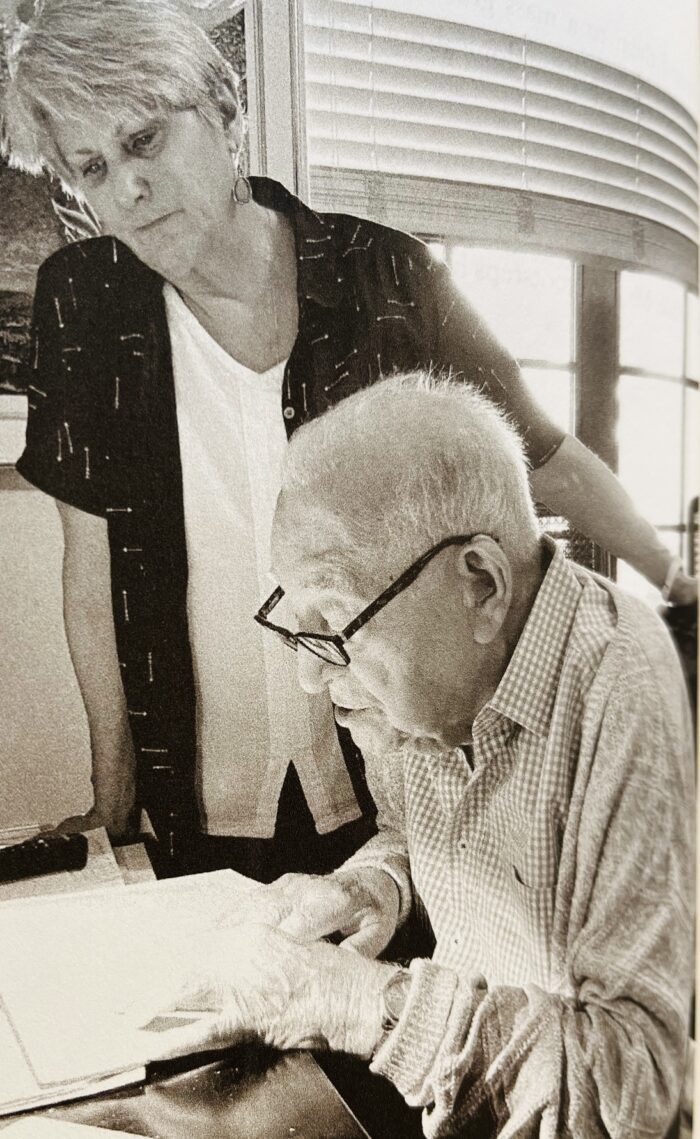

Sam Rakowski, a dogged Holocaust survivor who had passed through the Plaszow and Oranienberg concentration camps in Poland and Germany, was determined to ascertain what had happened to Hena Rozenek. In pursuit of this unresolved matter, he embarked on trips to Poland. Judy Rakowsky, who worked as a reporter for the Boston Globe and the Providence Journal, usually accompanied him.

She recounts their experiences in Jews in the Garden: A Holocaust Survivor, The Fate Of His Family, And The Secret History Of Poland In World War II, published by Sourcebooks. Far from being a laser-focused chronicle of the Holocaust, Rakowsky’s book also delves into the fraught topic of postwar Polish-Jewish relations.

As she states, Sam Rakowsky was well disposed toward Poland, never forgetting to mention that the Polish government refrained from collaborating with Germany. And he held fast to the belief that his warm pre-war relationships with local Poles would be useful in finding Hena Rozenek.

“He hoped they would still see him as one of them,” she writes. “He was that rare survivor whose enduring affection for his native country propelled him back there again and again … He still saw himself as a Pole, even though his nation had distanced itself from ‘Poles of Jewish nationality.'”

Judy Rakowsky was skeptical of her cousin’s rose-colored attitude to Polish Catholics “I felt sure they knew a lot more than they were sharing,” she says, noting that many had directly profited from the mass murder of Jews.

Furthermore, as she discovered, Poles who had assisted Jews were sometimes ridiculed and taunted by friends and acquaintances, leading to awkward situations in which rescuers were loathe to admit they had exhibited kindness toward Jews during the war.

To a great many Poles, Jews were invariably regarded as outsiders and perceived as supporters of Bolshevism who had welcomed the Soviet invasion of eastern Poland in September of 1939.

Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland had to contend not only with the unbridled brutalities of the Germans, but with mean-spirited Poles in Home Army partisan bands intent on wiping out Jewish survivors. Still other groups, including the National Armed Forces, were openly supportive of Germany’s genocidal campaign against Polish Jews.

“In fact, the killing of Jews … by the underground in 1944 was so widespread that a Jewish partisan group sounded the alarm to the Polish government-in-exile,” she says.

One Pole who had been convicted of killing Jews during that period, Wlodzimierz Bucki, was sentenced to 12 years in prison in the early 1950s, but was not actually incarcerated. He was pardoned in 1960, and in 1997, a regional court annulled his conviction altogether and ordered the government to pay court costs.

Despite such setbacks, Sam Rakowski persisted in his search for Hena Rozenek. Much to his disappointment, the International Red Cross failed to find her. Judy Rakowsky speculates that she may have chosen a new identity. One of her informants disclosed that she got married in 1946 and gave birth in 1947. “That’s as close as I got to finding a happy ending for Hena,” she says.

In resignation, Sam Rakowski eventually gave up looking for Hena Rozenek, opting to return to Poland on “trips that offered him more success and satisfaction.”

In the final pages of Jews in the Garden, she focuses on Poland’s approach to Jews and the Holocaust.

“Poland’s communist regime scrubbed from textbooks and monument narratives any references to (Germany’s) Final Solution for Jews. Instead, it portrayed all who perished in the war as equal victims of fascism.”

The right-wing government, which recently lost the general election after eight years in power, tried to fudge Polish responsibility for the 1941 Jedwabne pogrom out of a deep-seated conviction that Poles were “noble victims” of German aggression rather than rank perpetrators. “Even references to Jedwabne in theater and film struck a highly sensitive nerve,” she notes.

Critics who scolded the Polish government for conflating the genocide of Jews with the suffering of Christians accused it of engaging in “Holocaust envy” and creating a false equivalency.

Poles who had the courage to criticize Poles who had participated in the persecution, murder and dispossession of Polish Jews were attacked by certain academics and the right-wing media, she points out.

Jews who tried to reclaim their ancestors’ private properties were often depicted as greedy.

Negative cultural references to Jews still abound, with craft shops and kiosks selling zygki, or figurines of ultra-Orthodox Jews clutching coins or bags of money. Incredibly enough, Poles generally defend zygkis as symbols of good fortune, seemingly oblivious to the negative connotations they convey.

In Jews in the Garden, the author achieves two objectives. She delivers a fine detective story whose denouement has yet to be resolved. And she offers a probing analysis of Poland’s often contentious relationship with Jews.