Hamas has strenuously denied reports that Islamic State — the jihadist organization that has conquered wide swaths of territory in Iraq and Syria — is active in the Gaza Strip.

Responding to social media accounts that Islamic State had distributed fliers threatening 18 writers who had breached the “tenets of Islam” and warning women to cover their heads in accordance with Islamic law, a Hamas spokesman recently claimed, “We would like to reassure everyone that (Islamic State) does not exist in the Gaza Strip, and the security agencies are in full control of the situation.”

This claim may or may not be true, but that is really beside the point. What matters is that Muslim extremist groups that share Islamic State’s outlook and philosophy have sprung up in Gaza and have already clashed with Israel and Hamas.

This past June, the Israeli Air Force struck “global jihad-affiliated terrorists” in northern Gaza. One of the chief targets was Mohammed Awwar, a Hamas policeman who had joined an “extremist Salafi” group that had claimed responsibility for having launched rocket attacks against Israel during the Passover holiday, said an Israeli spokesman.

A few months before this incident, Israeli jets critically wounded Abdallah Kharti, a member of the Popular Resistance Committees. He had smuggled weapons into the Sinai Peninsula bound for the jihadist group Ansar Bayt al-Quds, which is locked in mortal combat with the Egyptian army.

In 2012, the Mujahideen Shura Council, a Gaza outfit with links to Al Qaeda, took credit for having fired a rocket at the southern Israeli town of Netivot. In the same year, an Israeli air strike killed two jihadists in Gaza who had carried out a number of terrorists attacks against Israel. They were identified as Hisham Ali Abd a-Karim Saidani, a member of Jamaat aal-Tawhid, and Ashraf al-Sabah, a founder of Ansar al-Sunnah. In a communique, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula expressed condolences for their deaths.

The then director of the Sin Bet, Yuval Diskin, estimated that about 500 “militant activists” in Gaza identify with and are in touch with Al Qaeda.

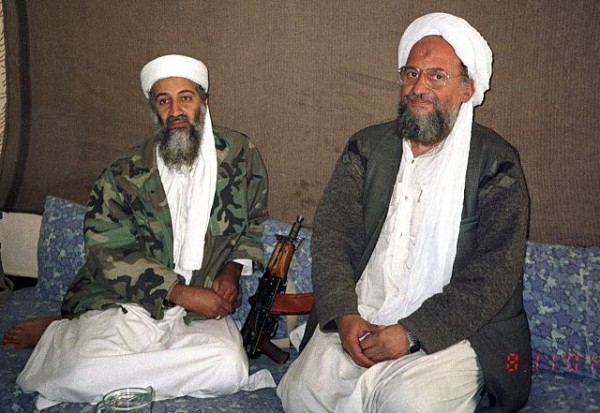

Although Al Qaeda focuses its attention on attacking targets in the West and the Arab world, it’s committed to destroying Israel. In 2008, on Israel’s 60th anniversary, the then Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden said, “We will continue our struggle against the Israelis and their allies. We are not going to give up an inch of the land of Palestine.”

The Palestinian cause is the most important factor driving Al Qaeda’s war with the West, he added.

Bin Laden’s successor, Ayman al-Zawahiri, is just as adamant. “Israel is a crime that should be removed,” he said in one of his anti-Israel rants.

The presence of jihadist groups in Gaza is hardly a secret.

Last July, at the height of the 50-day war in Gaza, the outgoing head of the U.S. Defence Intelligence Agency, Michael Flynn, warned Israel to refrain from trying to topple Hamas. He said, “If Hamas were destroyed and gone, we would probably end up with something much worse. The region would end up with something much worse.”

With Hamas out of the picture, he noted, Islamic State might attempt to fill the vacuum.

Around the same time, Michael Herzog, a former official in Israel’s Ministry of Defence, warned that an Israeli conquest of Gaza could have dire consequences. Writing in the Guardian, Herzog observed that Hamas could be supplanted by Islamic groups far more extreme.

Four years ago, a leaflet distributed by Jund Ansar Allah, a group affiliated with Al Qaeda, condemned Hamas for being moderate. Still reeling from an armed confrontation with Hamas during which some of its fighters were killed after a jihadist cleric had declared an Islamic emirate in Gaza, Jund Ansar Allah issued a stinging condemnation of Hamas: “Hamas’ actions serve the interest of the Jewish usurpers of Palestine and the Christians who are fighting Muslims in Iraq, Afghanistan, Chechnya and Somalia.”

According to Joshua Gleis and Benedetta Berti, the authors of Hezbollah and Hamas: A Comparative Study, the first jihadi/salafist groups in Gaza emerged in the early 1980s. Hamas, by contrast, was formed after the outbreak of the first Palestinian uprising in 1987.

Members of these jihadi groups were recruited from Fatah, Hamas and Islamic Jihad, they say.

Gleis and Berti claim that the jihadi camp in Gaza — which consists of groups like Jaish al-Islam and Jaish al-Ummah — grew exponentially in the months leading up to Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from Gaza in 2005 and following Hamas’ violent takeover of Gaza in 2007.

“Since then, the Salafi/jihadist movement has steadily grown within Gaza, and it now represents a loosely affiliated network of small organizations and operational cells whose main focus has been both attacking Israel and attempting to ‘Islamize’ Palestinian society by force. This has resulted in Hamas making its own efforts to further Islamize the Palestinian population of Gaza, in order both to appease the Salafis and to compete for their supporters.”

Palestinian jihadists who have adopted Al Qaeda’s extremist ideology have been very critical of Hamas — castigating it for having joined the Palestinian political system, excoriating it for its poor administration of Gaza, accusing it of having moderated its struggle against Israel, and taking it to task for having failed to impose Shariah law.

It’s debatable how deeply Islamic State has entrenched itself in Gaza, but what seems certain is that ideologically kindred organizations are already there.