Jimmy Carter, the 39th president of the United States, established a consequential record, at least insofar as the Middle East was concerned.

Carter, who passed away on December 29 at 100, was the only former president to reach that age. He will be buried in a state funeral on January 9.

By any measure, he was not a great president, that accolade being reserved for only George Washington in the 18th century, Abraham Lincoln in the 19th century and Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the 20th century.

Yet he left behind a legacy, having been the architect of Israel’s historic peace treaty with Egypt, its first one with an Arab state. This was an achievement of monumental proportions, and he will be remembered for it.

A one-term president who held office from 1977 to 1981, he was also instrumental in the passage of a bill to combat the Arab economic boycott of Israel, and in the establishment of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., one of the finest institutions of its kind.

Carter’s accomplishments were lauded and appreciated. But because he was supportive of Palestinian national aspirations, critical of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and its massive settlement project there, he was excoriated by right-wing Israeli nationalists and conservative Jews in the Diaspora.

His image as a principled peacemaker was further tarnished when he suggested that Israel was an apartheid state.

Promising to insert human rights considerations into the conduct of U.S. foreign policy, Carter was arguably the first American president to recognize the Palestinian cause.

On March 16, 1977, shortly after his inauguration, he told a town hall meeting in Massachusetts that, if the Palestinians recognized Israel’s right to exist, Israel would be duty bound to reciprocate. As he said, “There has to be a homeland provided for the Palestinian refugees who have suffered for many, many years.”

These were revolutionary words.

Until then, his predecessors had hardly acknowledged the simmering Palestinian problem, which lay at the heart of the Arab-Israeli conflict and had triggered a succession of wars.

Rightly or wrongly, Carter — a native of the southern state of Georgia and a progressive by its standards — compared the situation of the Palestinians to the plight of African Americans in the South, whose mistreatment he had witnessed on a first-hand basis.

Carter seriously thrust himself into this volatile issue following Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s precedent-shattering visit to Israel in November 1977.

Sadat, who succeeded Gamal Abdel Nasser following his untimely death in 1970, went to war with Israel in 1973 after Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir short-sightedly dismissed his peace overtures.

Like her myopic defence minister, Moshe Dayan, she preferred the option of retaining the occupied Sinai Peninsula rather than forging peace with Egypt, the preeminent Arab state which had fought five wars with Israel since 1948.

In the wake of the Yom Kippur War, which began when Egypt and Syria attempted to recapture the Sinai and the Golan Heights respectively, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger embarked on a relentless campaign of shuttle diplomacy to end the endemic violence.

Kissinger, the first Jew in that job, established cordial relations with both sides and managed to hammer out a disengagement accord with Israel and Egypt and then with Israel and Syria. These agreements led to Israel’s withdrawals from Egyptian and Syrian lands.

Breaking ranks with the Arab consensus on Israel, Sadat announced his readiness to address the Knesset in Jerusalem, whereupon Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin invited him to visit Israel. Sadat and his entourage arrived at Ben-Gurion Airport on November 19, 1977. They were greeted by Israeli dignitaries in a scene that would have been unthinkable only a few days earlier.

In exchange for peaceful relations with Israel, Sadat demanded Israel’s full withdrawal from the territories it had seized in the 1967 Six Day War. It was a demand that Begin and his cabinet firmly rejected, yet it set off a series of negotiations that ultimately involved the United States, Israel’s chief ally.

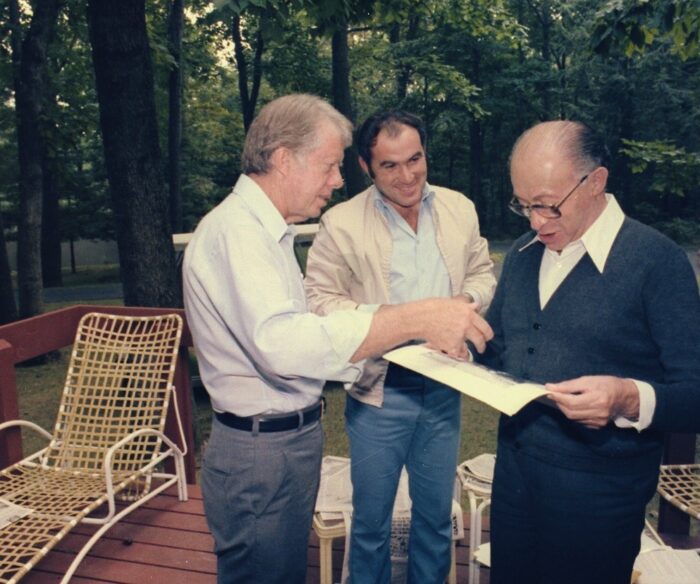

Israel’s talks with Egypt faltered, undermining their newly-minted rapprochement. Carter, seeking a meaningful role as a mediator, invited Begin and Sadat to the Camp David presidential retreat in Maryland to discuss the contentious issues. The summit took place in September 1978.

After 13 days of arduous negotiations, during which Begin and Sadat threatened to leave, success finally beckoned. Yet the Camp David Accords provided only framework for peace. A final agreement would have to be worked out in subsequent talks.

Much to Carter’s disappointment, Israeli and Egyptian negotiators failed to convert the Camp David understandings into a legally binding peace treaty. Carter, over the objection of his advisers, went to the Middle East to finish the task.

Israel agreed to pull out of the remainder of the Sinai in phased withdrawals. Egypt pledged to end its official hostility toward Israel and establish normal diplomatic relations with its former foe.

During this process, Sadat sought to include the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in the Camp David framework. As expected, Begin refused to consider a withdrawal from the West Bank or Gaza, a position that upset Sadat and Carter.

Begin agreed to grant the Palestinians “full autonomy,” no more and no less. Sadat, who had dreamed of a complete package of peace that resolved the Palestinian problem, had to content himself with a unilateral peace agreement with Israel.

Israel and Egypt, in a festive ceremony, signed the peace treaty in Washington on March 26, 1979. This seminal treaty has endured despite a number of crises, notably Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the outbreak of the second Palestinian uprising in 2000 and the Israel-Hamas war in 2014.

Carter should have received the Nobel Prize for peace, but the award went to Mother Teresa instead. Twenty three years would elapse before the Nobel committee officially recognized his stellar achievement and granted Carter the award.

Years later, he wrote Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid, a controversial book that blamed Israel for the lack of progress in ending the Arab-Israeli dispute and that implied that terrorism would continue until the advent of regional peace.

Amid a torrent of criticism, Carter admitted that the book’s title was “completely improper and stupid” and that it would be revised in future editions.

But the damage was done.

In 2015, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declined to see Carter during his visit to Israel. And in right-wing circles, Carter was demonized.

However he was perceived, Carter set the baseline for U.S. support of a two-state solution.

Ronald Reagan came out against Palestinian statehood, but he said he would not support “annexation or permanent control (of the occupied areas) by Israel.” As he put it on September 1, 1982, “Self-government by the Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza in association with Jordan offers the best chance for a durable, just, and lasting peace.”

George H.W. Bush, on October 30, 1991, said, “Throughout the Middle East, we seek a stable and enduring settlement. We’ve not defined what this means; indeed, I make these points with no map showing where the final borders are to be drawn. Nevertheless, we believe territorial compromise is essential for peace.”

Bill Clinton, on January 7, 2001, went one step further: “There can be no genuine resolution to the conflict without a sovereign, viable Palestinian state that accommodates Israelis’ security requirements and the demographic realities.”

Barack Obama, on June 4, 2009, underscored this theme in a speech in Cairo: “The only resolution is for the aspirations of both sides to be met through two states, where Israelis and Palestinians each live in peace and security. … Israelis must acknowledge that just as Israel’s right to exist cannot be denied, neither can Palestine’s. The United States does not accept the legitimacy of continued Israeli settlements.”

Obama’s successor, Donald Trump, endorsed a two-state solution, albeit in a truncated form.

The outgoing president, Joe Biden, has consistently championed Palestinian statehood.

Another legacy of the Carter administration was the Israel Anti-Arab Boycott Act, which prohibited American companies from cooperating with the Arab boycott against Israel.

When he signed the bill in 1979, Carter said, “For many months I have spoken strongly on the need for legislation to outlaw secondary and tertiary boycotts against American businessmen on religious or national grounds. During the campaign, I called this a profound moral issue from which we should not shrink. My concern about foreign boycotts stemmed … from our special relationship with Israel … The new law … seeks … to end the divisive effects on American life of foreign boycotts aimed at Jewish members of our society.”

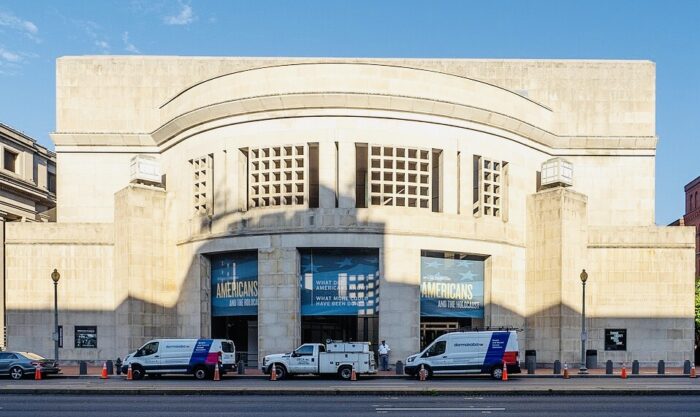

In another development, on November 1, 1978, Carter formed the President’s Commission on the Holocaust, charging it with submitting a report “with respect to the establishment and maintenance of an appropriate memorial to those who perished in the Holocaust.”

Chaired by the novelist and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel, it consisted of 34 members and included Holocaust survivors, lay and religious leaders of all faiths, historians and members of Congress.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum was opened on April 22, 1993. Since then, it has had 40 million visitors, including 10 million school children, 99 heads of state, and 3,500 foreign officials from over 211 countries and territories. By one estimate, less than 10 percent of visitors have been Jewish.

Its collection of materials includes 12,750 artifacts, 49 million pages of archival documents, 85,000 historical photographs, a list of registered survivors and their families, 1,000 hours of archival film footage, 93,000 library items, and 9,000 oral history testimonies.

Thanks to a special visa category created by the Carter administration, upwards of 50,000 Jews, Baha’is and Christians fleeing the Iranian revolution found refuge in the United States.

In addition, Carter pressured the Soviet Union to allow more Refuseniks — Jews who wished to emigrate — to leave. As a result, an additional 25,000 Jews were allowed to move to Israel or the U.S. annually.

When the Jewish dissident Anatoly (Natan) Sharansky was arrested in the Soviet Union in 1977 on charges of being an American spy, Sharansky’s wife, Avital, asked Carter to issue a statement on his behalf. Carter publicly stated that Sharansky was not a U.S. spy, paving the way for his eventual immigration to Israel.

These achievements are indelibly a part and parcel of Carter’s record.

Absent several major events abroad and at home, he may well have won a second term.

The lingering hostage crisis at the U.S. embassy in Tehran, the unsuccessful American commando raid to rescue the hostages, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the sharp downturn in the American economy badly marred his image, thereby enabling Reagan to win the presidency and hold it for the next eight years.

Four decades after his election to the highest office in the land, Carter’s accomplishments stand in sharp relief to his failures.