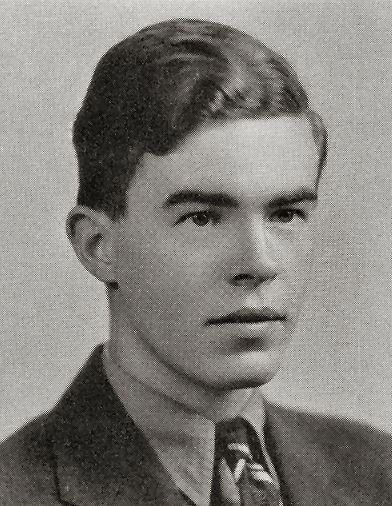

John Birch, an American missionary and U.S. army intelligence officer killed in China by communist troops in August 1945, earned acclaim and adulation only after his untimely death at the age of 27.

Hailed by his rabidly anti-communist admirers as the first casualty of the Cold War, Birch would become associated with right-wing extremism in the United States after retired businessman Robert Welch established the John Birch Society in 1958.

A precursor of today’s Tea Party movement in the Republican Party, the JBS was “one of the most influential and polarizing groups of its time,” writes Terry Lautz in John Birch: A Life, a superb biography published by Oxford University Press.

Dedicated to abolishing the federal income tax system, withdrawing U.S. membership in the United Nations, stopping foreign aid and supporting local police forces, the JBS was fiercely conservative and anti-communist.

Teetering on the edge of the lunatic fringe, it was hobbled by an image problem due to the perception of many Americans that it was a racist organization. Although Welch denounced the Ku Klux Klan, he opposed school desegregation and denounced the civil rights movement on the grounds that enforced desegregation was a violation of states’ rights. Rejecting the accusation that he was a bigot, Welch characterized racial equality as an admirable goal, but not if it was imposed or compromised individual liberties.

In this thoroughly researched book, China scholar Lautz suggests that Welch and his ideologically-driven associates were arch manipulators who used Birch as a vehicle for their political ends.

Currently a visiting professor at Syracuse University, Lautz describes Birch as “a brilliant student, a Christian fundamentalist and a dedicated soldier” who tried to help the Chinese people and protect China from Japan. “Welch reinvented this story, transforming the fallen hero into a martyr. He saw in Birch not only a man of conviction and purpose, but also a selfless soldier-patriot who courageously defended American values.”

To Welch, the “loss” of China to the communists in 1949 was a devastating setback that would not have happened had the United States displayed resolution and strength. Welch believed that China could have been America’s Cold War ally and bulwark against the Soviet Union had President Harry Truman stayed the course. In Welch’s view, Washington’s failure “to rescue China was … a case of duplicity, appeasement and betrayal.”

In Lautz’s judgment, Birch’s story is well worth telling. “It offers a window on the fanaticism of religion, the absolutism of war, the extremism of politics” and “the use and misuse of history.”

Lautz offers readers an analytical appraisal of Birch before moving on to Welch. Placing him in the camp of American missionaries, diplomats, businessmen and soldiers who hoped to transform China into a Christian, capitalist, democratic nation, Lautz goes on to describe his upbringing in the American heartland.

Raised in a traditional Baptist home, Birch went to China when it was mired in a war of of attrition pitting Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist army against the Japanese imperial army. The United States envisioned China as a force for peace, stability and democracy in Asia after the war, but American actions fell short of its rhetoric.

Birch hoped to win an appointment as a chaplain in the army, but was sent into the field as an intelligence operative because of his ability to read Chinese characters. According to Lautz, he proved to be an excellent officer, identifying potential targets, reporting on weather conditions and helping in the rescue of downed pilots.

On his last mission, following Japan’s surrender, he was sent to the northern Chinese city of Xuzhou. In an encounter with communist troops, he was killed by stray bullets.

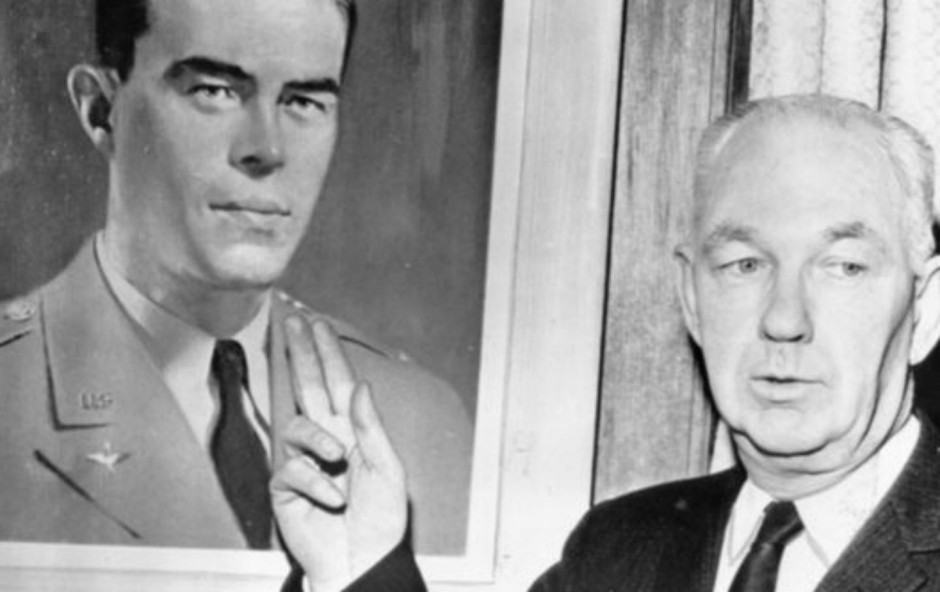

Welch discovered Birch in 1953, eight years after his death. While rummaging through documents in the Senate Office Building in Washington, D.C., he came upon a speech by Senator William Knowland, a Republican from California. In 1950, a few months after the outbreak of the Korean War, Knowland had paid tribute to a young American whom he called “the first casualty of World War III.” He was referring to Birch, of course.

Welch was then a former candy manufacturer who had never heard of Birch. But after reading about him, Welch was transfixed. In his mind, Birch’s death did not represent a random act of violence, but the opening shot of an ideological struggle. To Welch, a Harvard law school dropout, Birch was the acme of courage, honesty, decency and patriotism.

Smitten by his hero, Welch wrote The Life of John Birch: In the Story of One American Boy, the Ordeal of His Age. To ensure he had not died in vain, Birch and 11 colleagues, including Fred Koch — the father of billionaires and Tea Party supporters Charles and David Koch — formed the JBS. Its stated objective was mainstream: “less government, more responsibility and a better world.”

As Lautz notes, the JBS rapidly became “the most effectively managed and best financed grassroots conservative movement” in the United States. Its success, he adds, was due in no small part to Welch’s “considerable business acumen.”

Headquartered in the quiet Boston suburb of Belmont, the JBS mounted letter-writing campaigns, circulated petitions, placed newspaper ads, set up study groups, issued publications and managed a speakers’ bureau.

Welch claimed that “many of our finest chapter leaders are Jewish, and we are proud of our small but growing number of Negro members.” But as Lautz points out, Welch, for too long, tolerated the membership of Revilo Oliver, a JBS founder who dabbled in Holocaust denial. Welch did not expel him until 1966, by which time the damage had been done.

Welch also discredited himself, and the JBS, by claiming that President Dwight Eisenhower was a closet communist. No less a person than Richard Nixon, the vice-president who had made his reputation as an anti-communist crusader, condemned Welch for demagoguery and totalitarianism. Even Senator Barry Goldwater, a flaming anti-communist, had grave misgivings about Welch.

By the late 1960s, the JBS had faded from public view, supplanted by organizations to the right of it, says Lautz. Welch died in 1985, a few years before the Cold War ended and the Soviet Union collapsed.

The JBS still exists, but only on the margins, and the Tea Party now occupies its niche.

In closing, Lautz observes that Birch was neither a right-wing fanatic nor a patron saint. “With a profound sense of moral conviction he had come seeking to rescue and defend the Chinese … Instead, like so many other well-meaning outsiders, he became the unsuspecting victim of war and politics, forgotten in China and remembered in America only as a symbol of distorted historical memory.”