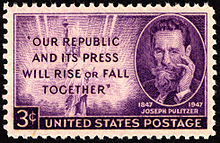

Joseph Pulitzer (1847-1911) was one of the giants of American journalism.

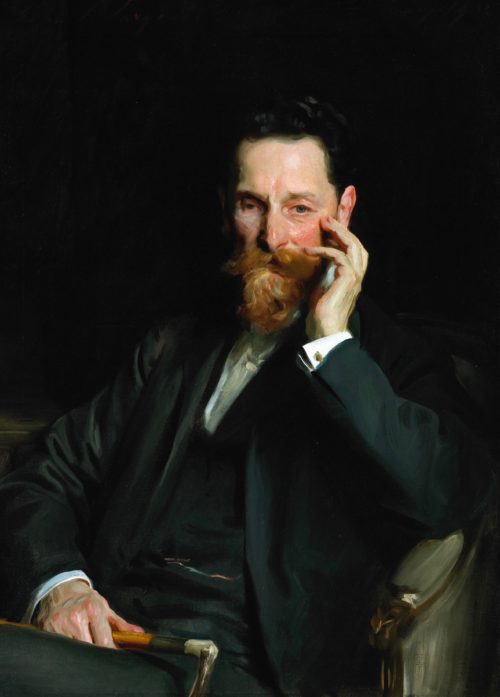

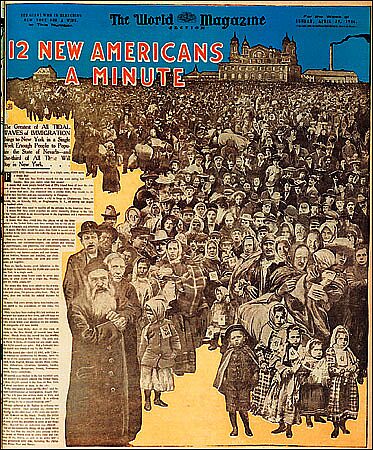

The owner and publisher of The St. Louis Post-Dispatch and The New York World, he was an exemplar of the rags-to-riches saga so beloved by Americans. Arriving in the United States as a penniless Jewish immigrant from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he finagled his way to the pinnacle of society.

Pulitzer’s odyssey unfolds in American Masters: Joseph Pulitzer on the PBS network on Friday, April 12 at 9 p.m. Directed by Oren Rudavsky, it’s a compelling documentary about a restless and driven entrepreneur who reshaped the daily newspaper.

Born in the Hungarian town of Mako, near Budapest, Pulitzer immigrated to America in 1864, one year before the end of the Civil War. To Pulitzer, the United States represented the glories of democracy, a cause to which he was utterly devoted.

Being illiterate in English, he joined a unit of the Union army where only German was spoken. Upon being demobilized, he headed west, shovelling coal aboard a Mississippi River barge, his first paying job. He taught himself English by reading the novels of Charles Dickens.

Landing in St. Louis, he bounced around before becoming a reporter for the Westliche Post, a German-language newspaper. He also dabbled in politics. Selling his shares in that publication, he bought a failing daily, The St. Louis Posst-Dispatch, which he turned into a glowing success. He demanded short, snappy, smart stories from his reporters, a formula that attracted legions of readers.

Pulitzer married Katherine Davis — a relative of Jefferson Davis, the president of the former Confederacy — in an Episcopalian church ceremony. Rudavsky suggests that Pulitzer was an assimilationist who wanted to shed his Jewishness. He succeeded. The Pulitzers are no longer Jewish.

The bulk of this documentary focuses on his acquisition and management of The New York World, which he purchased for $400,000 in 1883. Pulitzer wanted to reach a national audience and concluded that only a New York daily could provide him with such a platform. At that juncture, approximately a dozen dailies competed for readership, including The Morning Journal, the proprietor of which was Pulitzer’s brother, Albert.

A populist at heart, Pulitzer instructed reporters to write stories and features about the masses. As far as he was concerned, news was about ordinary people. But he insisted on accurate reporting. Accuracy is to a newspaper what virtue is to a woman, he said.

Being a liberal and a reformer, Pulitzer hewed to the principles of crusading and aggressive reporting. His newspaper exposed fraud, corruption and unethical business practices, but also called for the construction of more sewers to deal with a sanitation crisis and for the passage of laws to regulate conditions in tenements, where the majority of his readers lived in squalor.

And in a patriotic campaign, Pulitzer persuaded tens of thousands of New Yorkers to donate funds to build a pedestal for the Statue of Liberty, which graces New York harbor today.

From a purely aesthetic point of view, he was a trailblazer. He livened up the appearance of his newspaper, hiring illustrators and introducing color comic strips and sports coverage, among other innovations. Well-to-do New Yorkers looked down on The New York World, accusing it of being sensationalist, cheap and crude.

By the late 1880s, circulation had reached 400,000, making it the largest daily in the United States. Using the paper’s immense readership to his advantage, he charged department stores like Macy’s much higher rates for advertisements. Flush with cash, he built a stylistic building to house The New York World. For a while, it was the tallest structure in the city.

Toward the end of his life, he went blind and became hyper sensitive to sound. Turning into a recluse, he often lived on his yacht. The death of his young daughter had a depressing effect on him as well.

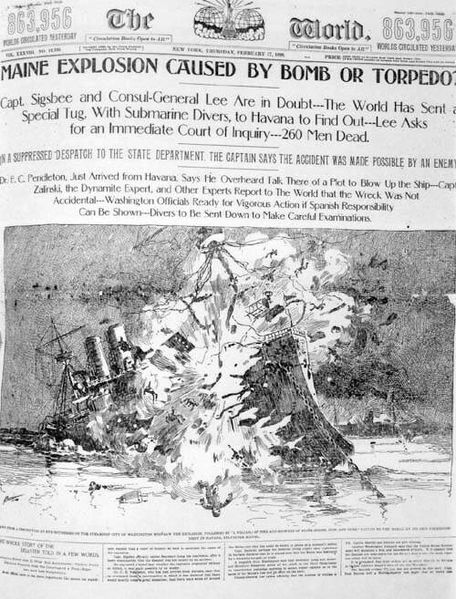

William Randolf Hearst bought Albert Pulitzer’s newspaper, renamed it The New York Journal, and went head to head with Pulitzer for new readers. Both publishers squeezed the 1898 Spanish-American War for all it was worth to boost circulation. Critics charged them with descending into “yellow journalism,” a phrase that would enter the American lexicon.

Being rich and powerful, Pulitzer challenged the legitimacy of President Teddy Roosevelt’s decision to build the Panama Canal, which would be his greatest accomplishment. Roosevelt threatened to imprison him, but in a landmark case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Pulitzer’s favor, thereby preserving an integral constitutional tenet, freedom of the press.

In the wake of Pulitzer’s death, The New York World went into decline. His sons eventually sold it to a buyer who changed its name. Adding insult to injury, the World’s headquarters was torn down to create better access to the Brooklyn Bridge. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch survived the upheavals, but it, too, was ultimately sold.

Pulitzer’s legacy, however, still shines brightly.

He created the Pulitzer Prize for quality in journalism and funded the establishment of the Colombia School of Journalism, still one of the finest schools of its kind in the United States.

Pulitzer was certainly a trailblazer.