Having read Thomas Keneally’s novel, Schindler’s List, Hollywood film director Steven Spielberg sought to turn it into one of his signature movies.

But where would it be shot?

Instead of some back lot studio in Los Angeles, he chose the southern Polish city of Krakow, where German manufacturer Oskar Schindler had saved hundreds of Jews by employing them in his pot and pan factory in Podgorze, a district south of the Vistula River that had been the site of a Nazi ghetto from 1941 onward.

Much to Spielberg’s disappointment, Podgorze was not suitable, having been so developed during the postwar era that it had lost its prewar flavour and authenticity.

So he headed to Kazimierz, a forlorn and dilapidated neighborhood north of Podgorze that had been an almost exclusively Jewish residential and commercial enclave before World War II.

He liked what he saw.

With its maze of cobblestone streets and historic buildings, including an unsurpassed collection of synagogues the Nazis had not bothered to destroy, Spielberg found the old-world atmosphere and color he had been looking for. And so Schindler’s List was filmed in Kazimierz.

That was more than 20 years ago. Since then, thanks to Spielberg’s foresight and a growing interest among Poles in Jewish history and culture, Kazimierz has evolved into a mecca for domestic and foreign tourists.

Its gentrification into one of Poland’s top tourist destinations amazes even long time residents of Krakow, one of the most beautiful cities in Poland and the venue of a successful annual Jewish cultural festival. As a local told me, “Kazimierz was desolate, the dirtiest, most neglected place in Krakow.”

Since its astonishing metamorphosis, Kazimierz has become such a draw that jaded observers have disparagingly compared it to Disneyland.

“Kazimierz is over-commercialized, too kitschy,” said Katarzyna Zimmerer, a local historian. “But it was unavoidable. It’s become so fashionable.”

Bristling with restaurants and cafes serving non-kosher Jewish-style food, kiosks dispensing an assortment of Judaica and trinkets, shops selling books on Jewish topics and boutique hotels catering to visitors from near and afar, Kazimierz is a manufactured still-life of a vanished world ruthlessly obliterated by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

Ewa Czuchaj, a guide, is hardly surprised that some Polish Catholics are inexorably drawn to Kazimierz. “Polish people want to know more about Poland’s Jewish past,” said Czuchaj, who was born in Novy Sacz, a town 100 kilometres from Krakow whose prewar population was half-Jewish. “It’s not a taboo subject any more.”

Separated by a wall from the Christian quarter until 1820, Kazimierz is nothing if not quaint.

Its heart and soul, Szeroka Street, resembles an elongated square. The synagogues and the historic Jewish cemetery for which Kazimierz is famous are found here and on Jozefa Street.

The Old Synagogue, a 15th century structure that has been repeatedly refurbished over the centuries, is said to be Poland’s longest-surviving shul.

The Remah Synagogue, founded by the Isserles family shortly afterward, adjoins a cemetery that was in use from the 150os to the 180os. The Popper Synagogue has been converted into a cultural center, as have the Kupa Synagogue and the Izaak Synagogue. The High Synagogue is used for cultural exhibitions, while the Tempel Synagogue, the only Reform congregation in Kazimierz, serves as a venue for the Jewish Cultural Festival, which starts toward the end of June.

Helena Rubinstein, the founder of the cosmetics empire, was born in Kazimierz. The house in which she was raised was boarded up and was in decrepit condition when I was last there.

The Hotel Ester is practically next door. Its glossy brochure proclaims in several languages, including English, Hebrew and German, that it is set “amidst a scenery that brings back the lost world of the Hassidim.”

The nearby Klezmer Hois, another hotel, offers Jewish delicacies ranging from Litvak herring to matzah ball soup and the foot-stomping music of Leopold Kozlowski, supposedly the last prewar klezmer musician in Poland.

Around the corner is Arka Noego (Noah`s Ark), a restaurant whose walls are festooned with charcoal drawings of rabbis and vintage photographs of traditional Polish Jews. Its menu features, among other items, carp, poultry, cholent, Galician salad and tzimmes.

Despite the profusion of cafes and restaurants serving old-fashioned Jewish cuisine, there is only one place here where kosher food is available, the Eden Hotel.

When I was in Kazimierz, I dropped into the Galicia Jewish Museum, which was founded by British photographer Chris Schwarz in 2004 to celebrate Galicia`s Jewish dimension and to dispel stereotypes and misconceptions about its Jewish inhabitants.

Prior to Germany`s invasion of Poland in 1939, the vast majority of Kazimierz`s 15,000 residents were Orthodox Jews. Secular Polish Jews in Krakow tended to live outside the boundaries of Kazimierz.

Krakow was occupied by the Germans on Sept. 6, 1939. By the summer of 1940, 35,000 Jews had been expelled from the city. About a year later, many of them were herded into the Podgorze ghetto. Catholics in Podgorze were resettled in Kazimierz.

In June 1942, the Nazis began to deport Jews to the Belzec extermination camp. The deportations are memorialized by a permanent exhibit of empty chairs fastened to iron pedestals in a cobblestone square in Podgorze.

Schindler`s workshops have been converted into a museum.

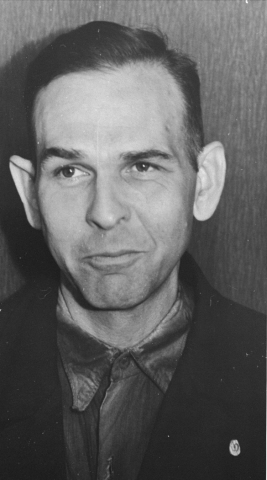

The Krakow ghetto was liquidated on March 13, 1943 by the SS commander, Amon Goth. With its liquidation, Krakow`s remaining 8,000 Jews were sent to the Plaszow concentration camp. A fragment of the original ghetto wall, some 30 metres in length, stands on Lwowska Street.

With the Red Army advancing on Krakow, Plaszow was hastily dismantled by the Nazis.

What`s left today is a sparsely wooded field in a semi-industrial area near a shopping mall.

A stylized monument on the ridge of a hill pays tribute to the victims.

Goth`s weathered grey villa, crowned by a mansard roof, is still on Heltnana Street.

It gives off eerie vibes, to say the least.