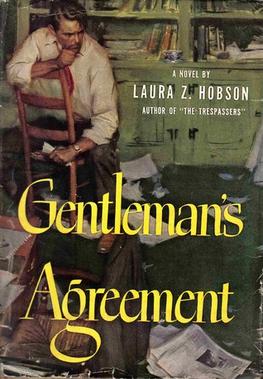

Laura Z. Hobson’s claim to fame is Gentleman’s Agreement, a disturbing novel about antisemitism in postwar America. Serialized in Cosmopolitan in 1946 and published in 1947 in book form, it was a blockbuster, selling 1.6 million copies.

Adapted for the screen by the playwright Moss Hart and directed by Elia Kazan, it starred Gregory Peck as Philip Green, a gentile magazine writer who poses as a Jew under the name of Greenberg to expose the insidious nature of anti-Jewish prejudice in the United States. Nominated for eight Academy Awards, Gentleman’s Agreement won three Oscars, including one for best picture of 1947.

Released by the Hollywood studio Twentieth Century Fox in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, the film promoted the theme that antisemitism was un-American. The second American movie of its kind after Crossfire, it was brought to the screen by Darryl Zanuck, who was once refused admittance to a Los Angeles country club on the mistaken assumption that he was Jewish.

Some critics claimed that Gentleman’s Agreement was more powerful than the novel itself, which may have annoyed Hobson, who died 28 years ago this month at the age of 85.

Hobson, whose maiden name was Zametkin, was born in New York City, the scion of Russian Jews who were socialists and Yiddishists. Her father, a journalist, was the editor of the Jewish Daily Forward.

Hobson, who changed her surname after marrying a non-Jewish publisher, was an arch assimilationist whose knowledge of Judaism was minimal, said Rachel Gordan in a paper on Hobson delivered on Feb. 13 at the University of Toronto’s Centre for Jewish Studies.

As she pointed out, Hobson, a journalist who had been in the advertising business, had no “clan feeling” or “special pride” in being Jewish. But she was aghast by the antisemitic practices, myths, covenants and restrictions that darkened and circumscribed the lives of Jews in the United States, and dedicated to the proposition that America should be a pluralistic and tolerant nation that valued ethnic and religious diversity.

Describing Gentleman’s Agreement as a landmark in American culture, Gordan said it blew the “whistle on American antisemitism.” It was so common, pervasive and acceptable that John Rankin, a Mississippi congressman and bigot par excellence, once stood up in the House of Representatives and, with impunity, brazenly called the syndicated columnist Walter Winchell a “little kike.”

Gordan, the The Ray D. Wolfe Postdoctoral Fellow at the U of T, said that Gentleman’s Agreement appeared at an opportune moment, when interest in American Jews was rising, when Judaism was increasingly regarded as one of America’s three major religions, and when antisemitism seemed to be on the wane.

In line with Hobson’s beliefs, Gentleman’s Agreement left Judaism on the margins of its narrative, adopting the view that antisemitism was a Christian American problem rather than a Jewish one.

Lee Wright, Hobson’s editor at Simon & Schuster, was initially skeptical that she could put herself in the shoes of Green, the fearless journalist who exposes the depth and breadth of antisemitism in the United States.

Richard Simon, Simon & Schuster’s publisher, tried to dissuade Hobson from finishing the book, believing that antisemitism was not an appropriate topic for a novel. A Jew, he did not want to rock the boat, said Gordan.

Possibly, Simon was thinking of Hobson’s previous novel, The Tresspassers (1943), which fared poorly. A novel about non-Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany, it did not ring a bell in readers’ hearts.

But after the appearance of Strange Fruit, a controversial 1944 novel about interracial romance, Simon reconsidered, saying that a “great Jewish book” had yet to be written. “Perhaps you are the one to do it,” he said in a reference to Hobson.

Hobson was ahead of her times in bringing timely social issues, such as antisemitism, to a mainstream audience, said Gordan. “She was an an author of protest literature,” she noted, adding that Hobson’s vision of a more inclusive post-war America was prescient.

Nonetheless, Hobson is rarely, if ever, included in the canon of American Jewish literature simply because her novels were not sufficiently “Jewish.” And to this day, oddly enough, some scholars who specialize in the field do not even know she was Jewish.