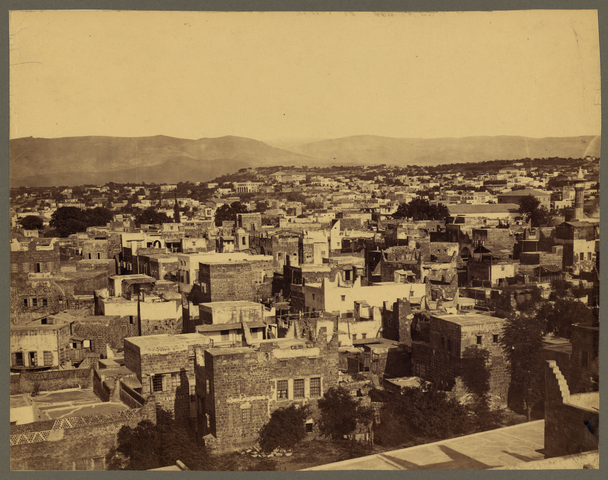

The area on the Mediterranean coast known as Lebanon has been a battleground for thousands of years, long before it became a sovereign state in 1943, with Beirut as its capital.

But only since the 1970s has it become a victim of almost permanent violence between its various religious factions, who have often enlisted outside support, including, at times, neighboring states like Israel, Iran, Syria and Saudi Arabia, as well as the Palestinians.

Of these Lebanese groups, by far the most successful has been the Shiite Hezbollah.

Hezbollah created this inextricable link by asserting control over all aspects of Shiite lives, establishing cultural and educational centers, charities, media and propaganda outlets, and professional societies. Its network of schools exceeds anything offered by the state.

The party comprises about 10 percent of the Lebanese parliament and holds two cabinet positions in the coalition Beirut government.

Hezbollah also presents itself as the country’s savior and protector against both Israel and Sunni extremists in nearby Syria. It often claims the latter groups, including the Islamic State, are American and Israeli creations. Its forces are now helping Bashar al-Assad’s beleaguered Alawite regime in Syria.

As the party’s deputy leader Naim Qassem has declared, Hezbollah’s goal is not just to raise a fighting force, but to transform Lebanon’s Shiites as a whole into a “Society of Resistance.”

Lebanon’s political feuds remain as byzantine as ever. In mid-January, two of the country’s most prominent Christian politicians, one an ally of Hezbollah, the other a longtime foe, struck a surprise agreement that could help end the standoff that has left the country without a president for nearly two years.

The country’s legislators have failed to elect a successor to Michel Suleiman, who left office in May 2014, despite meeting more than 35 times.

Samir Geagea, the leader of the Lebanese Forces party, threw his support behind the presidential candidacy of his rival, Michel Aoun, whose Free Patriotic Movement is Hezbollah’s main Christian ally in Parliament, as part of the March 8 alliance. (Lebanon’s confessional political system requires that the president be a Maronite Christian.)

Aoun and Geagea had been enemies since both were generals in rival Christian camps during the Lebanese civil war between 1975 and 1990.

“I announce General Michel Aoun’s candidacy for the presidency of the republic,” Geagea said at a joint press conference. “I call on our allies to endorse Aoun’s candidacy.”

This struck a blow at Saad Hariri, the son of Rafik Hariri, a former prime minister assassinated by the Syrians in 2005. He is the leader of the Future Movement, the largest Sunni party and the main political rival of Hezbollah.

Until now, Geagea’s party had been the Future Movement’s largest Christian ally in the parliamentary bloc known as the March 14 Coalition, formed to oppose the domination of Lebanon by Hezbollah.

Hariri has now switched his support to Suleiman Franjieh, leader of the Marada movement, a political party formed in 2006 from a former militia group based in the northern city of Zgharta.

The internal quarrels in Lebanon reflect the wider conflict between Iran and Saudi Arabia, the representatives of, respectively, Shi’ite and Sunni Islam.

The country has become a major front in the ongoing Riyadh-Tehran feud, with both sides investing billions of dollars to support their respective candidates.

When an angry mob torched the Saudi embassy in Tehran on Jan. 2 in response to Saudi Arabia’s execution of Nimr al-Nimr, a Shi’ite cleric, the Arab League issued a statement to condemn the government of Iran.

Lebanon was notably absent when the organization voted in favor of Iran’s condemnation, which led the Saudis on Feb. 19 to retract a $4 billion military aid package to train and equip the Lebanese army and security forces. Riyadh warned its citizens against travelling to Lebanon, and accused Hezbollah of smuggling drugs into the kingdom and sending mercenaries to Yemen.

On March 2, the Saudi-led six-member Gulf Cooperation Council designated Hezbollah a terrorist organisation. It has even threatened to deport Lebanese expatriate workers, some half a million of which work in the Gulf.

But, as Hanin Ghaddar, managing editor of Lebanon’s English-language NOW News, has noted, Hezbollah is now so strong that neither the GCC declarations nor Saudi Arabia’s escalations worry them unduly.

Hezbollah thinks these measures will only weaken the Lebanese state and the Shiite group’s opponents in the March 14 camp, which has called on Hezbollah to withdraw from Syria. Should the latter decide to confront Hezbollah, it has the arms and will to defeat them.

In a speech delivered in late January, the party’s secretary-General, Hassan Nasrallah, stressed Hezbollah’s determination to continue its regional role as a military force and warned it is ready for any conflict these pressures could produce.

Lebanon, which is home to over one million Syrian refugees, is on the brink of sectarian violence and a proxy war. But all external efforts to weaken Hezbollah have only strengthened its popular support and given the party’s leadership more power within its community.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.