Early on in her book, Reckonings: Legacies of Nazi Persecution and the Quest for Justice (Oxford University Press), Mary Fulbrook writes, “The Nazi past continues to disturb.”

What an understatement.

In this massive and erudite work, Fulbrook — a professor of German history at University College in London — delves deeply into an interrelated web of themes: the complicity of ordinary Germans in the formation of a racist, totalitarian regime, the unparalleled crimes of Nazi Germany, the effect they had on the postwar West German state, and the record of West Germany in the prosecution of Nazi war criminals.

It’s a complex and difficult subject, but Fulbrook is up to the task.

The majority of Germans “fell into line one way or another,” she says, referring to their explicit or tacit support of the new order. Nazi Germany was a society in which people “increasingly turned a blind eye to the violence and inhumanity of a system that, in everyday life, they themselves helped to enact and sustain.” In short, there was widespread complicity and collusion.

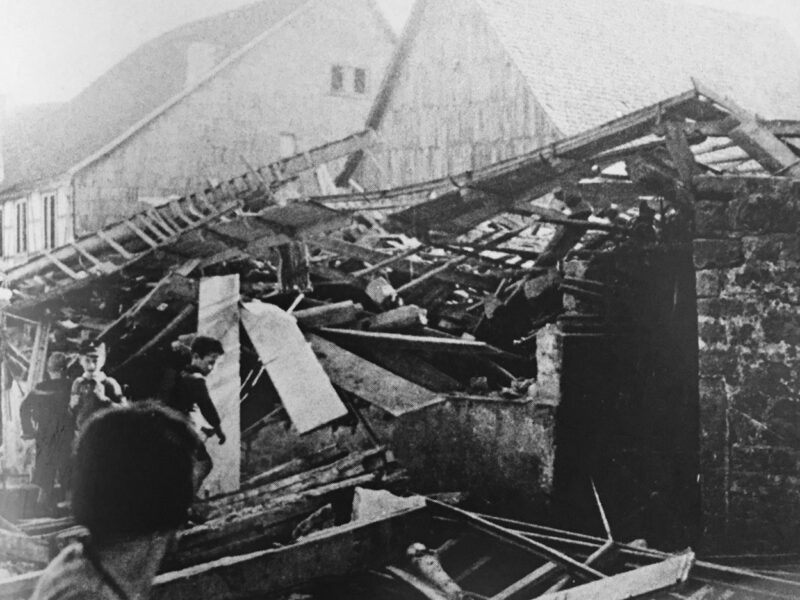

Large numbers of Germans were active participants in Kristallnacht — the nation-wide pogroms of 1938 that spelled finis to the Jewish community — though some were shocked by it.

Nazi concentration camps in Germany were not tucked away in remote areas. Sachsenhausen was connected to a train line near Berlin. Buchenwald was close to Weimar. And in Nazi-occupied Austria, Mauthausen was near Linz, where Adolf Hitler had attended school.

As she points out, the organized murder of civilians began in Germany with the euthanasia program, which claimed the lives of several hundred disabled Germans. It was headquartered in a villa that had been owned by a Jewish businessman, Georg Liebermann, the brother of the painter Max Liebermann.

Germany’s invasion of Poland, which triggered World War II, was marked by a campaign of genocide against Polish Jews, whose complicated relationship with Polish Christians had been punctuated by occasional tensions and periodic explosions of violence. During Germany’s occupation, the Germans exploited these fault lines.

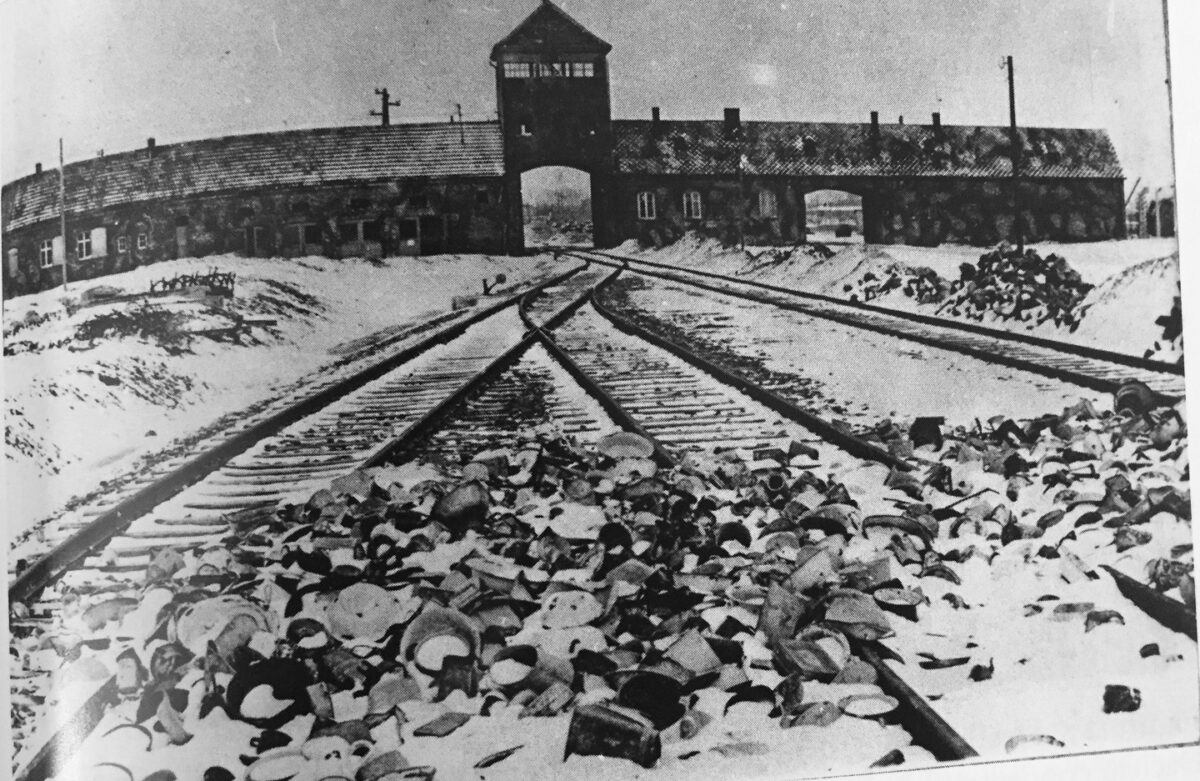

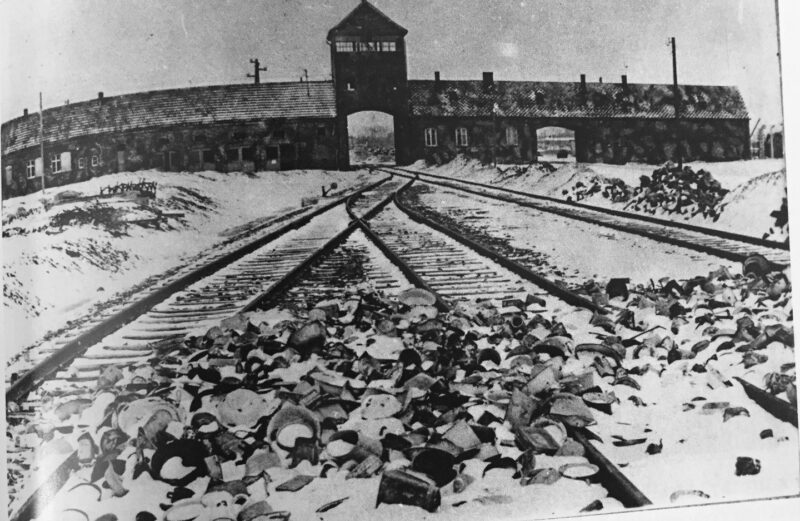

Hans Frank, the governor of Nazi-occupied Poland, swiftly realized that three million Polish Jews could not be simply shot to death, but had to be exterminated by much more efficient means. His deadly ruminations gave rise to the Chelmno gas vans and camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau and Treblinka.

Yet, as Fulbrook observes, this new method of murdering Jews on an industrial scale did not prevent the Nazis from reverting to old forms of mass slaughter. On November 3, 1943, in a one-day massacre called Harvest Festival, 43,000 Jews were shot in the Majdanek concentration camp under the direction of Nazi functionary Christian Wirth.

Fulbrook speculates that from 200,000 to one million Germans and European collaborators were actively involved as perpetrators. Some were willing killers. Still others had to be pressured into embracing their role. What seems certain is that millions of German civilians more or less knew what was happening in Poland. It was not a deep, dark secret.

The chairmen of Nazi-appointed Jewish Councils were tacitly complicit in the Holocaust, but they had no choice in the matter. Some, like Adam Czerniakow of Warsaw, behaved decently, caught between conflicting demands. Others, like Chaim Rumkowski of Lodz, were intoxicated by their limited and fleeting powers.

After the war, a few Jewish survivors, including Abba Kovner, a resistance fighter in Lithuania, contemplated extreme forms of revenge, such as poisoning the water supply of German cities. Former Nazis sought to rewrite the past, employing strategies for denying their guilt, evading responsibility, or even rebutting the accusations themselves.

Several high-ranking Nazi officials who had served in the killing fields of Poland were executed there. Rudolf Hoss, the former commandant of Auschwitz, and Hans Biebow, the administrator of the Lodz ghetto, were hanged in 1947. Amon Goth, the former commander of Plaszow, went to the gallows in 1946.

In western Germany and Austria, de-Nazification programs were patchy, and former Nazis were rapidly reintegrated into society.

Thousands were brought to trial, but only a small proportion were even investigated. Major German industrialists, such as Friedrich Flick and Alfred Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, got off quite lightly.

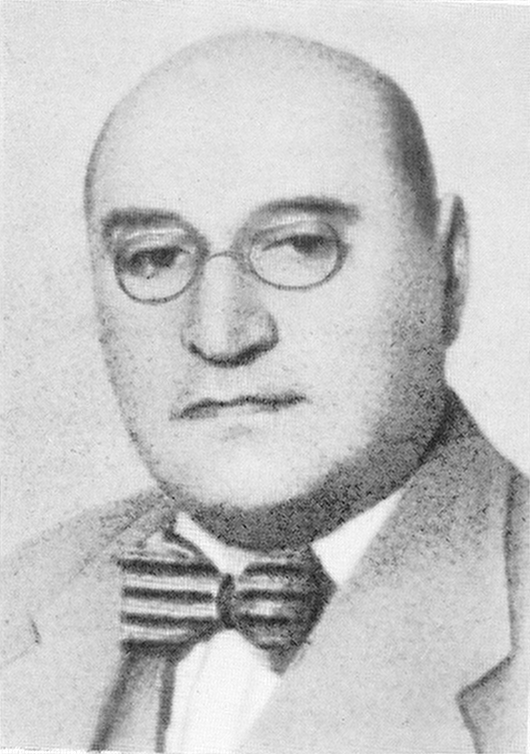

Fritz Bauer, a Jewish official in the West German government, tipped off Israel about the war criminal Adolf Eichmann, who had fled to Argentina. He assumed Eichmann would receive far too sympathetic a hearing in West Germany. As it happened, Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem was a turning point in the discussion of the Holocaust.

Nonetheless, several high-profile trials took place in West Germany from the 1960s onward.

The Frankfurt Auschwitz trial, which lasted from 1963 to 1965, stimulated intense media interest and public debate. And it played a vital role in establishing a place for the Holocaust among German historians and readers.

The Operation Reinhard death camp trials, which focused on Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka, took place during the same period.

The last major concentration camp trial in West Germany was lengthy in duration. Unfolding between 1975 and 1981, it cast a spotlight on Majdanek, situated on the outskirts of Lublin.

The last important Nazi war criminal to be prosecuted was Josef Schwammberger, whose trial occurred in 1991 and 1992, following Germany’s reunification. Having escaped to Argentina with the connivance of the Vatican’s infamous “ratline,” he was given frequent assistance by the German embassy in Buenos Aires.

East Germany, a communist state, acted more vigorously than West Germany in prosecuting Nazi war criminals. “Overall, former Nazis in East Germany had roughly six or seven times the chance of being prosecuted and found guilty than they would have had if living in the West,” says Fulbrook.

Konrad Adenauer, West Germany’s first chancellor, acknowledged responsibility for Nazi crimes in a speech to the Bundestag in 1951. And under the 1952 Luxemburg accord, he agreed to pay financial compensation to the Israeli government and the World Jewish Congress to absorb Holocaust survivors in Israel and the Diaspora.

Fulbrook argues that the Holocaust has become central to the identity and culture of contemporary Germany, judging by the memorialization of the victims of Nazism.

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, which opened in 2005, lies in the very heart of Berlin, next to the iconic Brandenburg Gate and a short walk from the renovated Reichstag building and the ultra-modern chancellor’s office.

The Topography of Terror museum, located on the site of the former Gestapo headquarters, shines a light on the perpetrators. The House of the Wannsee Conference, in a leafy and upscale suburb of Berlin, commemorates a seminal 1942 meeting of top-level Nazi officials in which the Final Solution throughout Europe was formally approved.

The impact of the Holocaust on the children of survivors is examined in methodical fashion by Fulbrook.

“Born into marriages founded on tragedy, these children grew up almost suspended in time, haunted by a past they had not themselves experienced,” she says. “Many defined their identities in terms of the ways in which the unexperienced past had shaped them.”

Fulbrook also paints a revealing portrait of the children of perpetrators. While Heinrich Himmler’s daughter, Gudrun, remained devoted to her father, Hans Frank’s son, Niklas, rejected him completely.

Still others engaged in projects that often led to a heightened interest in Judaism and, in some cases, to marriages with Jews and conversions to Judaism. One perpetrator’s son went as far as changing his name and identity, becoming a rabbi and moving to Israel.

As Fulbrook correctly maintains, the Nazi interregnum had a profound effect on Germans and Jews alike.