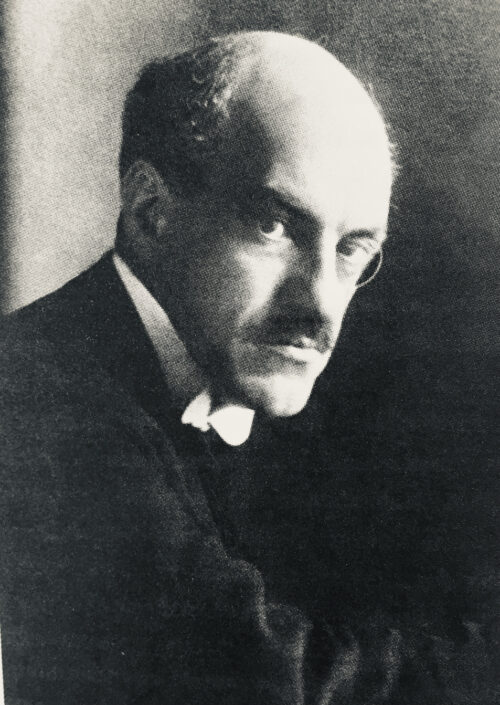

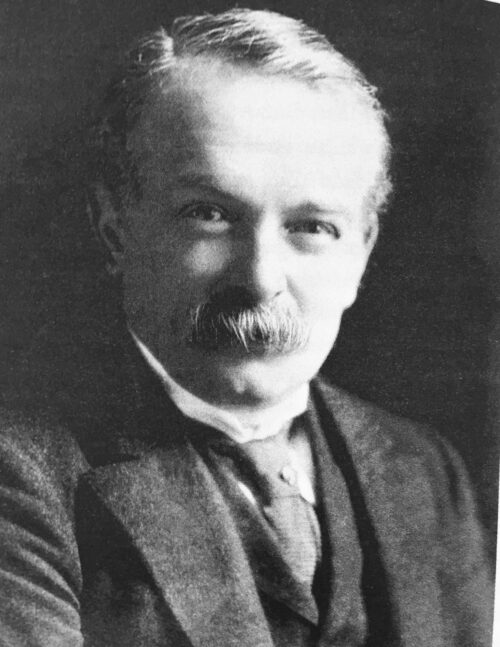

Britain laid the groundwork for the emergence of Israel when, in 1917, it promised to facilitate the establishment of a “national home” for the Jewish people within the boundaries of Palestine.Two of its leading politicians, Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Foreign Minister Arthur Balfour, played an integral and indispensable role in this historic process.

Gardner Thompson, a British historian, traces the arc of this seminal development in Legacy of Empire: Britain, Zionism And The Creation Of Israel, published by Saqi Books in London. A specialist in British colonial policy in Africa, he argues that the Arab-Jewish conflict in Palestine was precipitated by Zionist colonization and fostered by Britain.

He believes the Zionist movement could not have persuaded Britain to back its objectives without the outbreak of World War I. As a corollary, he contends that, without the support of Christian Zionists like Lloyd George and Balfour, the Balfour Declaration would have remained a gleam in the eye of prominent Zionists such as Chaim Weizmann.

Thompson, in his pro-Palestinian account, considers legitimate Jewish historical claims to Palestine, but dismisses them. And he laments that the Palestinians paid the ultimate price for the persistence of European antisemitism, one of the root causes of Jewish settlement in Ottoman Palestine.

Russian pogroms, combined with the Alfred Dreyfus affair in France and the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany, shattered the myth that assimilation could eradicate antisemitism and impelled a minority of Jews to regard Palestine as a solution to the so-called Jewish Question.

Thompson’s empathy for Jewish suffering in 19th and 20th century Europe comes shining through, but his sympathy for the Palestinian cause is far stronger. He portrays Jewish settlers in Palestine — the ancestral home of the Jewish people — as interlopers, and he refers to Israel as a “European colonial settler state.”

Although he sides with the Palestinians as the victims of British duplicity and Zionist power, Thompson is anything but a crude propagandist. He’s a seasoned historian with a knack for research and a prose style of crystalline clarity. These essential skills are the drivers of his narrative, which focuses on the formation of the Zionist movement, the Jewish settlement of Palestine, the Palestinian Arab reaction, the policies pursued by the British, and the armed conflict between Jews and Palestinians.

Zionism, as he correctly observes, was a marginal movement in the Diaspora in the 19th century and even after that. Ultra-Orthodox Jews considered it blasphemous. Socialists affiliated with the Bund labelled it as a “counter-revolutionary fantasy.” Assimilated bourgeois Jews feared it would undermine their hard won position in society.

As he suggests, only the most zealous Zionists settled in Palestine. Jews intent on leaving Europe preferred the United States, Canada or Argentina, among other countries.

A decade before Theodor Herzl founded the modern Zionist movement, upwards of 3,000 members of the Russian-based Lovers of Zion organization moved to Palestine, joining about 30,000 Sephardic and Ashkenazic Jews who had gone there for religious, economic and personal reasons.

By 1914, around 85,000 Jews resided in Palestine out of a population of 700,000. One hundred thousand Jews had immigrated to Palestine since the 1880s, but about half departed, unable to cope with its harsh conditions.

Myopically enough, Zionists often tended to overlook the presence of Arabs in Palestine, preferring to think it was an empty land. Thompson claims the new Russian arrivals aroused Arab fears that Jews were trying to take over the country and marginalize them. “In short, Zionism was destroying the trust that had existed in Palestine between Jews and their Arab neighbors,” he says in a debatable assertion. “Political Zionism rendered Arab-Jewish rapprochement in Palestine impossible.”

From the outset, Jews bought land from mostly absentee Arab landlords at exorbitant prices. “Land is the most necessary thing for establishing roots in Palestine,” wrote Zionist official Arthur Ruppin. Yet by the 1920s, Jews had purchased only 116,000 out of 8.2 million cultivable dunams. These purchases aroused fears of dispossession in the Arab community.

While some Arabs prior to World War I accommodated themselves to the Jewish influx, the majority feared that Zionists were building the foundations of a future Jewish state. They were right, of course. From the earliest days of Jewish immigration, as Thompson points out, Arab-Jewish clashes occurred. Warning of the birth of a Palestinian national consciousness, Weizmann wrote in 1913, “The Arabs are beginning to organize. They consider Palestine their own.”

As early as 1905, the Maronite assistant governor of Jerusalem, Najib Azouri, warned of Jewish attempts to “reconstitute on a very large scale the ancient kingdom of Israel” and predicted that the Zionist and Arab national movements “are destined fight each other continually until one of them wins.”A few years later, the editor of Al Karmil, an Arabic newspaper in Haifa, urged Arab absentee landowners to stop selling land to Jews.

The Arab consensus was that the Jewish historic connection to Palestine rested on a slender thread, a specious claim that Thompson erroneously accepts at face value.

“For some, the deepest flaw in the Zionist version of Jewish history was its dependence on the Bible, rather than, say, archeology,” he adds. What he neglects to mention is that a panoply of archeological digs have conclusively proven the unbroken link between Jews and ancient Israel.

Thompson says that the fortunes and prospects of Zionism improved markedly after Britain’s entry into World War I. Herbert Henry Asquith, the prime minister, thought that Palestine was of limited strategic value, but the only Jewish member of his cabinet, Herbert Samuel, was a Zionist who believed it would help Britain secure control of the Suez Canal, the gateway to India, the crown jewel of its overseas possessions.

In 1915, Asquith asked an official, Maurice de Bunsen, to determine what British policy should be toward the Ottoman Empire. While suggesting that Palestine was of minor importance, he recommended that the port of Haifa should be developed so as to provide support for British interests in Mesopotamia, or Iraq.

Several months later, Britain’s high commissioner in Egypt, Henry McMahon, initiated a correspondence with Hussein bin Ali, the sharif of Mecca and a descendant of the prophet Mohammed. The upshot of their exchange was that Britain recognized the Arab right to independence in the Middle East.

Britain and France, in the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement, divided up the region, in contravention of McMahon’s promise. Palestine did not appear by name on the map and was referred to as the “brown area.” Haifa would be the Mediterranean terminus for Britain’s railway line to Baghdad. By that juncture, Lloyd George had succeeded Asquith as prime minister, a position he would hold until 1922.

In 1916, the British operative T.E. Lawrence encouraged the Arabs under Faisal Hussein to revolt against Ottoman rule. As the rebellion gathered momentum, Britain conquered the Sinai Peninsula and Palestine.

With the outcome of the war still very much hanging in the balance, Balfour sent an historically-charged 67-word letter to Lord Rothschild, the president of the Zionist Federation. The Balfour Declaration, dated November 2, 1917, viewed with favor the creation in Palestine of “a national home for the Jewish people,” but noted that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.”

The most passionate opponent of the Balfour Declaration in the British government was a Jew. Edwin Montagu, the secretary of State for India and an ardent assimilationist, marshalled four arguments against it. The most salient one was that a designated Jewish homeland would confirm the gentile prejudice that Jews were aliens and foreigners in the nations in which they resided.

Thompson credits Weizmann with having convinced Britain to issue the declaration. He persuaded the British that Jews in Russia and the United States were crucial to their respective countries remaining in the war. A year earlier, Balfour’s predecessor, Lord Grey, had said that “Jewish forces” in the U.S. and elsewhere were largely hostile to Britain due to its alliance with antisemitic czarist Russia.

“Under considerable pressure to break the stalemate against Germany and to secure victory, British policy-makers were susceptible to Zionism,” Thompson writes. “The reality was very different from the picture that Weizmann so skillfully painted. The power of ‘International Jewry’ was a fiction … an antisemitic delusion.” Quoting the Columbia University historian Michael Stanislawski, he says that American and Russian Jews exerted little or no influence. “Yet it was on this basis that Britain decided to sponsor the Zionist cause.”

C.P. Scott, the editor of The Manchester Guardian, said that Lloyd George, a pious Christian who cherished the Bible, was deeply influenced by Weizmann. In his diary, Scott wrote, “Palestine was to him the one really interesting part of the war.” Thompson adds, “Lloyd George’s personal commitment to Zionism in Palestine was a necessary condition for the Balfour Declaration … Devoted to an imagined Palestine and a notion of resurrecting something of a splendid past, he fell easily under the spell of Weizmann and succumbed to the Zionist dream.”

Practical considerations also swayed Britain to adopt a pro-Zionist stance. Weizmann, a Russian chemist who acquired British citizenship in 1910, invented a propellant of immense military value and, much to Britain’s gratitude, made it available to its army at no cost.

Interestingly enough, Weizmann, who would be Israel’s first president, did not demand a Jewish state. “We asked only for conditions which would allow us to build a Jewish state in the future,” he told David Ben-Gurion, who would be Israel’s first prime minister. “It (was) simply a matter of tactics.”

Britain acquired Palestine as a mandate from the League of Nations in 1922. From the outset, the Palestinians were vehemently opposed to Britain’s sponsorship of Zionist colonization, hoping Britain would rescind the Balfour Declaration and offer them self-government in all of Palestine.

Arab violence had already broken out in 1920. Referring to the comments of Thomas Haycraft, a British official who submitted a report on the strife, Thompson implies that the Arab disturbances were anti-Zionist rather than antisemitic. Haycraft wrote, “So long as the Jews remained an unobtrusive minority, as they did under the Ottoman government, they were not molested or disliked.” Haycraft’s remark is implicitly condescending, suggestive of the view that Jews had no genuine claims to Palestine, but Thompson regards it as the gospel truth.

Thompson goes on to say that many British officials in Palestine were hostile to Zionism in general and to the Balfour Declaration in particular, regarding it as an impediment to establishing law and order. Yet some officials hewed to the belief that Palestine was a strategic asset to Britain and that Zionist capital could essentially subsidize the mandate.

Certainly, Samuel — the first non-baptized Jew to sit in the cabinet and the first high commissioner in Palestine — belonged to that school of British administrators. He concurred with Zionist dogma that the Arabs would reap economic benefits from Jewish immigration and settlement.

“The Jewish influx of manpower, capital and enterprise served British economic and financial interests,” says Thompson, “but it fuelled Arab opposition at unprecedented levels.” In his opinion, all the ingredients for “irreversible antagonism” — Jewish immigration, land purchase and settlement — were in place by 1923, two years before Samuel left his post in Palestine.

Samuel contributed indirectly to the mounting tension by engineering the appointment of Haj Amin al-Husseini as the mufti of Jerusalem. Samuel assumed he could be manipulated to serve British interests, but this would not be the case in the long run.

In the meantime, the Jewish and Arab communities grew apart. And because they did not share a common language, he notes, “prejudice and anxiety grew unchecked.”

With Nazi persecution of Jews growing increasingly serious and Polish Jews coming under economic pressure from the state, Jewish immigration from Germany and Poland to Palestine picked up considerably, changing its demographic posture. While Jews comprised 10 percent of Palestine’s population and owned two percent of its land in 1920, they accounted for 28 percent of its inhabitants and owned five percent of its land in 1935.

The illegal immigration of Jews to Palestine from 1920 to 1939 is estimated to have been 40,000.

“Arab perception of rapidly growing immigration, settlement (and) land sales was a primary underlying cause of the violent disturbances of the later 1930s,” he writes in a reference to the 1936 Arab revolt in Palestine against British rule and Jewish settlement.

The Arab Higher Committee, led by the mufti of Jerusalem and composed of Muslims, Christians, moderates and radicals, spearheaded the campaign against the Yishuv, the Jewish community of Palestine. Arab boycotts of Jewish businesses were counter-productive because they pushed the Jewish economy toward greater self-reliance and prompted the British to recognize Tel Aviv as an independent port alongside that of Jaffa’s.

In 1937, the Peel Commission concluded that the “national aspirations” of Jews and Arabs were “incompatible” and recommended the division of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states. The Arabs rejected the plan set out by Lord William Peel.

Jettisoning Peel’s partition plan, Britain released a White Paper in 1939 calling for a drastic reduction in Jewish immigration and land sales to Jews and the imposition of a unitary state in Palestine. “This was an evident tilt towards Arab interests,” says Thompson, agreeing with the assessment of pro-Israel scholars that the White paper marked the end of Britain’s commitment to Jews under the Balfour Declaration and ruled out a Jewish state.

The White Paper came to nothing, having been rejected by Jews and Arabs alike, but it was indicative of Britain’s desire for an exit strategy from the morass of Palestine, which was virtually ungovernable.

Nevertheless, Zionism triumphed, having emerged as “a formidable and irresistible force” on the eve of World War II. But as Thompson says, the Yishuv’s success could only be accomplished at the expense of the Palestinians, who refused all offers of compromise.

Throwing up its hands in despair, Britain, in 1947, announced its intention to leave Palestine and hand over responsibility for its future to the United Nations. As Thompson explains, Prime Minister Clement Attlee made that decision due to an “intolerable situation on the ground, financial constraints and strategic retrenchment.”

No sooner had the United Nations in 1947 voted to partition Palestine than the Yishuv was confronted by an Arab guerrilla war, which dragged on from November to May 1948. After Ben-Gurion declared statehood, five Arab armies attacked Israel. During this period, 700,000 Palestinians, representing two-thirds of Palestine’s population, fled or were compelled to flee.

“The bonfire which David Lloyd George laid, Arthur Balfour ignited, and British imperial and mandate governments fanned thereafter until the heat forced them to abandon it has continued to burn …” writes Thompson somberly.