Countries ranging from China and Jordan to India and the United States are experiencing water shortages. Yet strangely enough, Israel — a semi-arid nation whose annual rainfall has dropped by half in recent years — does not face a water crisis. As Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu put it, “Israel doesn’t have a water problem.”

Indeed, Israel is blessed with a water surplus and even exports water to one of its Arab neighbors.

In Let There Be Water: Israel’s Solution For A Water-Starved World (Thomas Dunne Books), Seth M. Siegel explains in lucid and authoritative fashion how the Jewish state developed a highly sophisticated approach to the management of water, one of the scarcest resources in the Middle East and a cause of political and military instability there.

Siegel, an American lawyer, writer and entrepreneur, describes Israel as one of the most water-conscious nations on the planet. “Israel today has a dynamic, capitalist economy,” he writes, “but with a state-controlled, centrally planned approach to water.”

Theodor Herzl, the founder of the modern Zionist movement, recognized the importance of water. In his novel, Altneuland, one of the characters says of Jewish settlement in Palestine, “This country needs nothing but water and shade to have a very great future.”

Water is a perennial theme in Israeli culture.

Israel has honored water in its currency and postage stamps. And in novels by Amos Oz and A.B. Yehoshua, two of Israel’s finest writers, water appears as a theme.

Siegel identifies Simcha Blass, an immigrant from Poland in the early 1930s, as one of the central figures in Israel’s water regimen. He and a few others, including Levi Eshkol, a future Israeli prime minister, planned and created Mekorot, the water company that was so important in the expansion of agriculture in pre-state Israel. As well, Blass developed a plan to pipe water from the water-rich north to the water-challenged south.

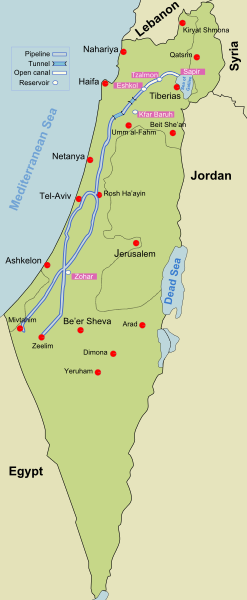

The concept came of age in the National Water Carrier, which was officially opened on June 10, 1964. With a capacity of 120 billion gallons, it cost six times more to build than the Panama Canal.

As Siegel suggests, it enabled Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, to fulfill a cherished promise — to make parts of the Negev Desert bloom. Thanks to the National Water Carrier, Israel pushed the desert from just south of Rehovot — a short drive from Tel Aviv — to Beersheba and points southward.

But because the National Water Carrier drew on water from the Jordan River, tensions flared between Israel and Syria.

Blass also invented the drip irrigation system, which is more efficient than sprinkler irrigation. Scorned by critics at first, the idea caught on after a kibbutz agreed to manufacture, promote and sell drip irrigation equipment.

Drip irrigation has two advantages, says Siegel. It can save as much as 70 percent on water usage, and it produces a larger and usually higher quality harvest. Today, drip irrigation is the norm in Israel, with 75 percent of all irrigated fields watered by it. Israel has exported the technology to 110 countries.

Israeli plant geneticists played a pivotal role in water conservation by coming up with a new breed of tomato. Meanwhile, Israeli seed breeders developed fruits and vegetables — melons, peppers and eggplants — that thrive in brackish water, the salty water found in abundance beneath the sands of the Negev.

“By growing a significant amount of the country’s fruits and vegetables using otherwise undrinkable water — and using it to spur a multi-billion-dollar agricultural export industry — Israel is able to improve its citizens’ diets and enhance its economy, without putting a strain on its freshwater resources,” says Siegel.

Amazingly enough, Israel reuses more than 85 percent of its sewage water after it has been properly treated. And Israel was the first country to adopt the mandatory use of the dual-flush toilet. The Israel Water Authority claims that this device results in a saving of about 13.5 billion gallons per year.

In addition, Israel is a leader in rain-cloud seeding, which adds as much as 10 percent to the rainfall over the Sea of Galilee, Israel’s sole freshwater lake.

Israel, too, has been a pioneer in desalting sea water, a process known as desalination.

“Israel now produces nearly 500 million gallons of freshwater from salty sources every day,” writes Siegel. “Desalination has entirely transformed the water profile of Israel. The extensive use of desalinated water has had enormous implications for Israel’s environment, economy, infrastructure, social harmony, public health and even its relationship with its Palestinian, Jordanian and other neighbors.”

Israel’s “hydro diplomacy” has worked wonders.

As part of its 1994 peace treaty with Jordan, Israel agreed to provide it with about 14 billion gallons of water per year and to store its water reserves from the Yarmouk River in the Sea of Galilee.

Israeli water engineers have been active in China and India. Before the Islamic revolution in Iran, the majority of water projects there were supervized by Israelis.

Despite its achievements in water management, Israel has made some serious mistakes, having polluted the Yarkon and Jordan Rivers, notwithstanding the laws that supposedly protect them. In recent years, however, the Yarkon has been cleaned up.

Graphs at the end of the book underscore Israel’s success in having diversified its water resources. The bulk of its water is derived from aquifers, followed by desalinated seawater, treated sewage, brackish water and the Sea of Galilee.

Israel has come a long way from the days when water shortages were quite common and an inhibitor to growth and development.