Buttenheim, population 3,000, is a speck of a town in southern Germany. Normally, you would drive through without paying it the slightest heed. Set amid the green pastoral countryside of the Regnitz Valley in Upper Franconia, between the historic cities of Bamberg and Nuremberg, it’s quiet, rustic and almost quaint.

Despite its obscurity, Buttenheim has carved out a unique niche for itself, even if only because of an accident of history. It`s the birthplace of its most famous son, Levi Strauss, who created a blue jeans empire in his adopted land, the United States, and it`s the home of a museum in his honor, the only one of its kind in the world.

Strauss, whose original first name was Loeb, was born on Feb. 26, 1829, the youngest child of Hirsch and Rebecca. Hirsch was a cattle dealer — a trade that attracted a disproportionate number of Jews in the 19th century — and then an itinerant hawker of fabrics.

Back then, there was a small Jewish community in Buttenheim, whose origins date back to the mid-15th century.

When Hirsch died in 1846, the family was thrown into poverty, prompting Rebecca to travel to Bamberg — now a UNESCO World Heritage site — to apply for immigration papers. Having received the required documents on June 4, 1847, the family — Strauss, his mother and two sisters — travelled 600 kilometres north to the port of Bremenhaven to board a ship for the voyage to America.

Strauss`two brothers, Jonas and Louis, were already there, waiting to be reunited with their mother and siblings.

The perilous crossing to New York City took six weeks. Sanitary conditions aboard the vessel were appalling. There was neither heating nor ventilation. Passengers slept on mattresses made of straw and dried seaweed.

Some died before reaching the Promised Land.

Jonas and Louis, who had established a dry goods business in Little Germany, a quarter later known as the Lower East Side, met them in New York City.

Blessed with grit and an adventurous spirit, Strauss went to St. Louis to sell his brothers`supplies. He was such an adept salesman that Jonas and Louis sent him westward to California to open a store in San Francisco, which was booming due to the Gold Rush.

He sold goods that prospectors needed — apparel, bedding, combs, purses and canvas for tents — and prospered.

As Strauss grew rich, a tailor from Latvia who had lived in western Canada, Jacob Davis, began making a new product, work trousers reinforced with copper rivets. He wanted to patent the process, but could not do so without an investor.

Strauss, from whom Davis had bought fabric, was his man.

On May 20, 1873, they received patent 139,121 from the United States Patent and Trademark Office, launching a new era in the garment trade.

The patent would revolutionize the clothing industry, add a fresh wrinkle to casual wear and herald the arrival of denim blue jeans in the United States.

This story of entrepreneurial vision is recounted in the Levi Strauss Museum, which opened 14 years ago and is housed in a two-storey renovated half-timbered building at 33 Markstrasse.

The tour starts on the ground level, where the Strauss’ originally lived, and continues on the upper floor. Exhibits trace the arc of Strauss’ life from Buttenheim to San Francisco, while a display of jeans and a loud musical video clip celebrates the connection between modern American culture and jeans.

A gift shop sells jeans, shirts, jerseys, belts and mugs.

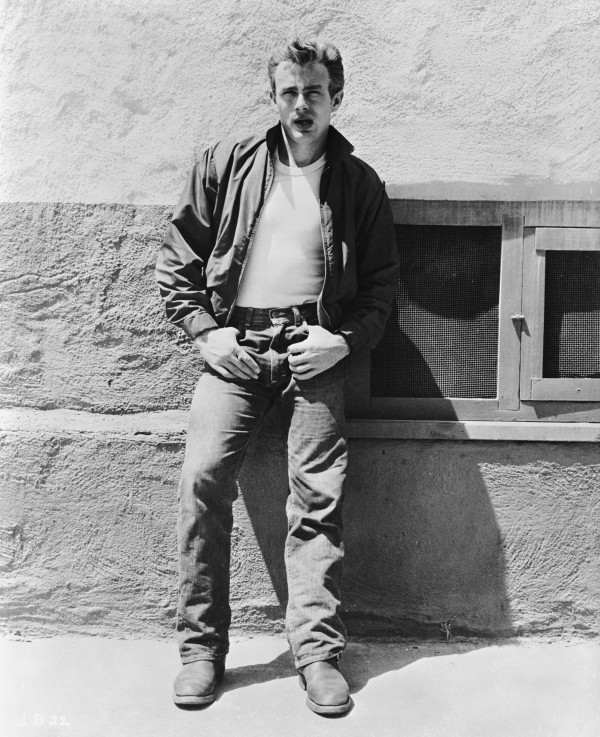

As I moved from exhibit to exhibit, I learned that jeans were first favoured by miners, railway workers, cowboys and lumberjacks. Young people were drawn to jeans after World War II. By all accounts, the actor James Dean, in the Hollywood movie Rebel Without A Cause, greatly popularized jeans, which, in the 1950s, represented youth rebellion.

In the Soviet Union and the satellite states in Eastern Europe, jeans would epitomize liberty.

These days, jeans are as common as cherry blossoms in the spring and are worn, by among others, farmers, construction workers and stylish men and women around the globe.

The exhibits also tell us that Strauss, a bachelor, died in San Francisco on Sept. 26, 1902 at the age of 73. He left the business to his four nephews, Abraham, Jacob, Louis and Sigmund Stern — the sons of his sister, Fanny, and her husband, David.

Four years after Strauss`death, an earthquake destroyed the company headquarters, but it was rebuilt and continued to grow as jeans, a symbol of freedom and independence, became increasingly popular in North America and abroad.

Today, the Strauss brand faces stiff competition from a plethora of global brands, but jeans, regardless of the manufacturer, remain remarkably popular internationally.

Who could have known that a poor Jewish boy from an obscure town in Germany would spark a sartorial revolution of this magnitude?