The Holocaust exacted a terrible toll in Greece. Seven out of ten Greek Jews were murdered by the Nazis. But on the scenic Ionian Sea island of Zakynthos, something very different happened. All 275 of its Jewish residents survived thanks to the humanity and courage of a bishop and a mayor and the assistance and silence of the island’s Christians.

Drey Kleanthous tells this incredible story in Life Will Smile, an upbeat documentary that will be screened online by the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from October 22 to November 1.

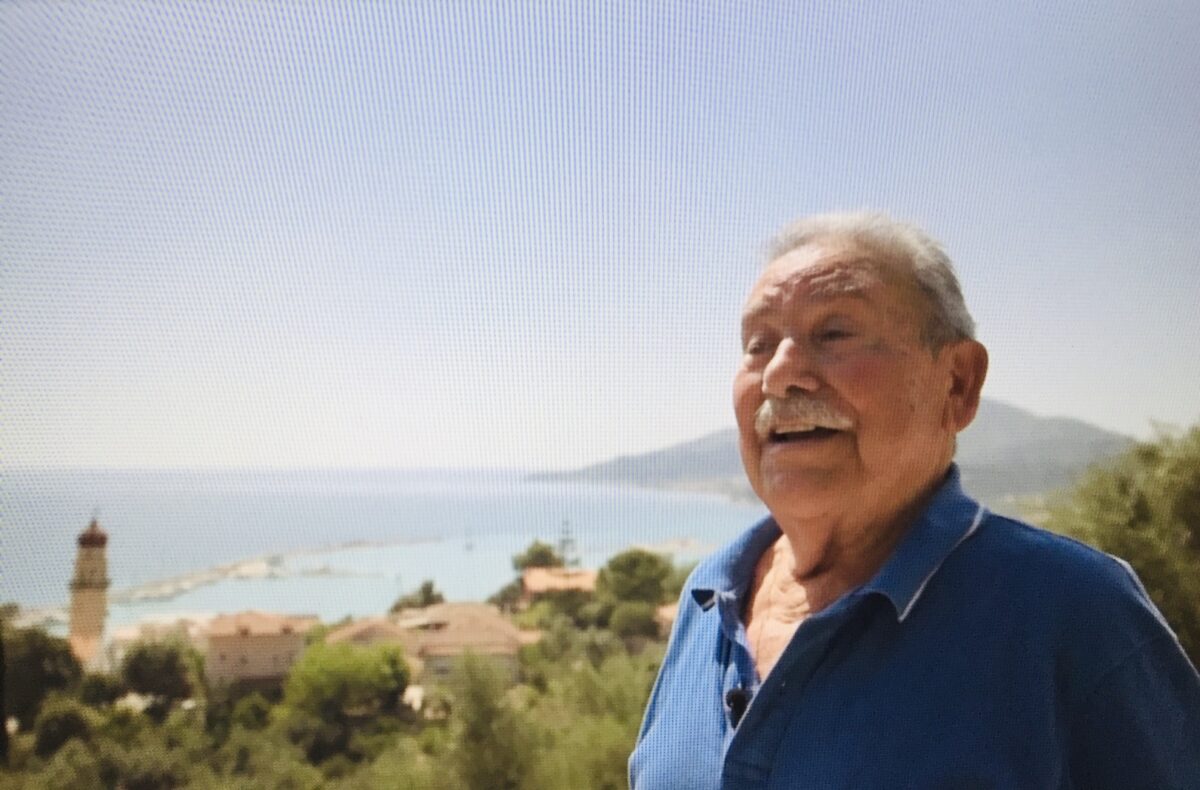

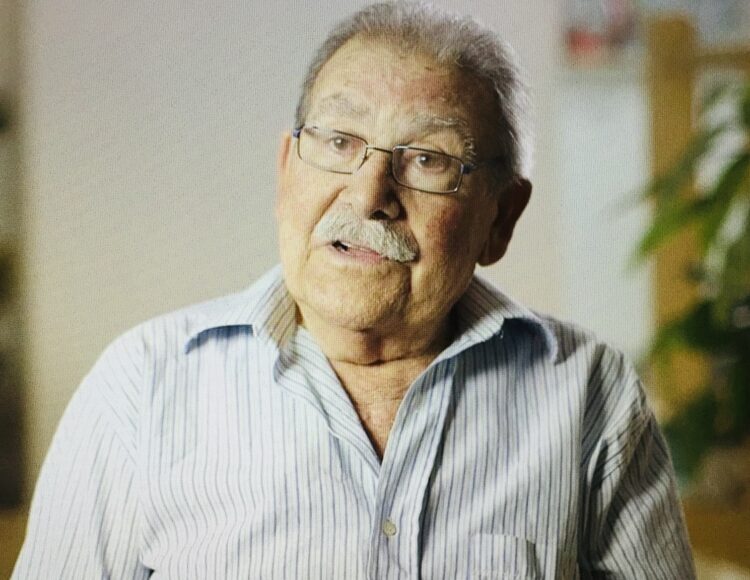

One of the Jewish survivors, Konstantantinis Samul Haim, is the narrator. He was 10 years old when the Germans took over Zakynthos in September 1943 with the express purpose of deporting its Jewish inhabitants and sending them to a Nazi extermination camp on Poland. Haim’s version of events is supplemented by reenactments.

Haim is an optimistic, cheerful person. Having been saved by Christians, he speaks fulsomely of the neighborly relations that Jews and Christians enjoyed on the rugged 405 square kilometre island before, during and after the German occupation.

“We lived like brothers and sisters,” he says. “We were like family. We never felt restricted or frightened.”

Zakynthos was first occupied by the Italians in the autumn of 1940. According to Haim, it was a fairly benevolent occupation that had no adverse effect on its 35,000 residents.

“For us, the war started when the Germans arrived,” he adds.

The German attachment, commanded by Alfred Luth, pulled into Zakynthos in September 1943. By then, the Jews of northern Greece, particularly in Salonika, had been deported to the Auschwitz extermination camp.

Haim’s father, an itinerant peddler, got a taste of German brutality when his goods were arbitrarily seized.

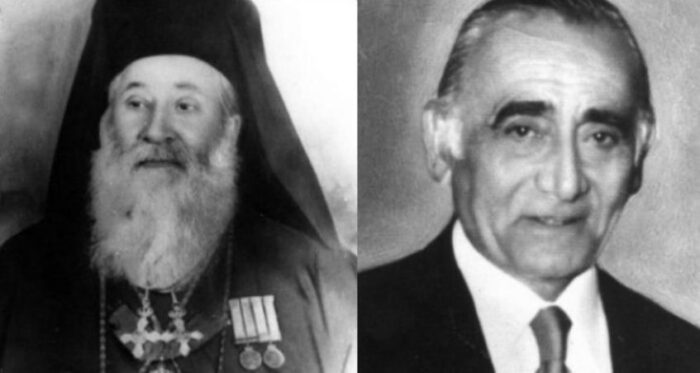

The German commandant summoned the island’s bishop, Chrysostmos, and its mayor, Loukas Karrer, to his office and demanded a list of the Jewish families. Chrysostmos and Karrer supposedly told him that Jews did not live on Zakynthos. When the German mentioned that there were two synagogues on the island, they countered by saying that the Jews were Christians.

The bishop then advised Jews to leave their homes and find refuge with islanders.

Flummoxed by their lack of cooperation, the Germans interrogated Haim’s uncle, Moshe Ganis, a Jewish community leader who was ordered to produce the required list. In the meantime, Chrysostmos and Karrer handed the Germans a doctored list containing only their names.

Fearing for their lives, Chrysostmos and Karrer fled to a nearby island. Haim thinks they were captured by the Germans and tortured.

Haim and his family found shelter with farmers who worked their fields during the day. They remained there for five months, but it felt like an eternity.

Haim seems amazed that no one betrayed the Jews, but notes that his uncle and his family on the island of Corfu were deported to and killed in Auschwitz.

He believes the Jews of Zakynthos were spared for one compelling reason. “We were Greeks too,” he says, referring to their cordial relations with Christians. He is grateful that a tragedy was averted. “No words can do justice to the gratitude we feel,” he says.

The film ends on a distinctly positive note. In 1978, Yad Vashem — the Holocaust memorial and education centre in Jerusalem — designated Chrysostmos and Karrer as Righteous Gentiles. Later, a memorial in their honor was built in Athens.

Oddly enough, Kleanthous fails to mention that Jews no longer live on Zakynthos. The majority made aliyah in 1946 and most of the rest left after the 1953 earthquake, which caused widespread destruction and destroyed the old Jewish quarter and its two synagogues.

The last remaining Jewish inhabitant, Ermandos Mordos, died in 1982, leaving Zakynthos bereft of Jews.