More than 50,000 prisoners perished in the Buchenwald slave labor camp in Germany, and if fortune hadn’t intervened, the death toll would have been 168 higher.

In the summer of 1944, in contravention of the Geneva Convention on the treatment of prisoners of war, 168 Allied airmen — pilots, gunners, radio operators — were incarcerated in Buchenwald, near the city of Weimar. They were on the cusp of being executed when they were saved by two German air force officers.

Their story is told in a taut documentary, Lost Airmen of Buchenwald, which can be watched on the Netflix streaming network. Michael Dorsey’s film unfolds over a one-year period between 1944, when they were captured in Nazi-occupied France, and 1945, when they finally gained their liberty.

The airmen, from Canada, Britain, Australia, New Zealand and the United States, found refuge in Paris after they were shot down. Betrayed by a French collaborator, they were imprisoned by the Germans in a local jail after having been accused of being “terror pilots.”

Along with French resistance fighters, they were crammed into boxcars and spent the next five miserable nights on a train heading toward Buchenwald. During the course of the film, several of the survivors, including an American named Joe Moser, recall their ordeal in tempered flashbacks.

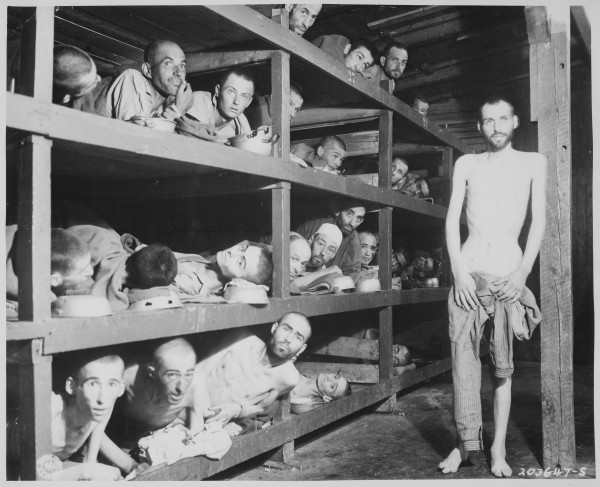

When they arrived after a tortuous journey, they saw barbed wire fences, guard towers and, most ominously, the chimney of a crematorium. Having expected to be sent to a POW camp, they were shocked to learn that Buchenwald was a concentration camp. The smell of burning flesh and the presence of haggard men confirmed their worst fears.

Stripped naked, they were deloused, completely shaved and handed old, mismatched clothes to wear. Three men had to share a blanket in barracks unfit for human beings. They subsisted on a sub-standard diet designed to induce starvation within three months. Despite the appalling conditions, a pilot says, Buchenwald was not an extermination camp like Auschwitz.

Shortly after their arrival, Allied bombers bombed a nearby armaments factory, but errant bombs fell on Buchenwald, destroying barracks and killing countless prisoners. The raid sounded like the roar of one thousand trains, a prisoner remembers. The airmen were sure they would be killed in retaliation for the bombardment, but strangely enough, they were spared.

Not long afterward, they found out that a group of British commandos were also being held in Buchenwald. To their horror, almost all of them were strangled to death on meat hooks or fatally shot. They paid the price for the air raid.

Around this time, two German air force officers met the airmen, who bitterly complained that Buchenwald was no place for POWs. The Germans agreed, and the airmen were soon transferred to a POW camp holding 10,000 men. Their departure from Buchenwald came just in the nick of time, before their scheduled execution.

But after Buchenwald, life for the airmen was hardly a bed of roses. With the war winding down, they were subjected to a gruelling 65-mile death march to smaller camps in Germany.

Looking back, the airmen say they rarely talked about their imprisonment in Buchenwald after the war, possibly because some people didn’t believe they had been there. Still others assumed they had been sent there because they were Jewish, which, in fact, was not true. On a positive note, they learned to savour life to the fullest and appreciate the value of freedom and the importance of tolerance.

For many of the airmen, Buchenwald was a life-changing chapter in their lives.