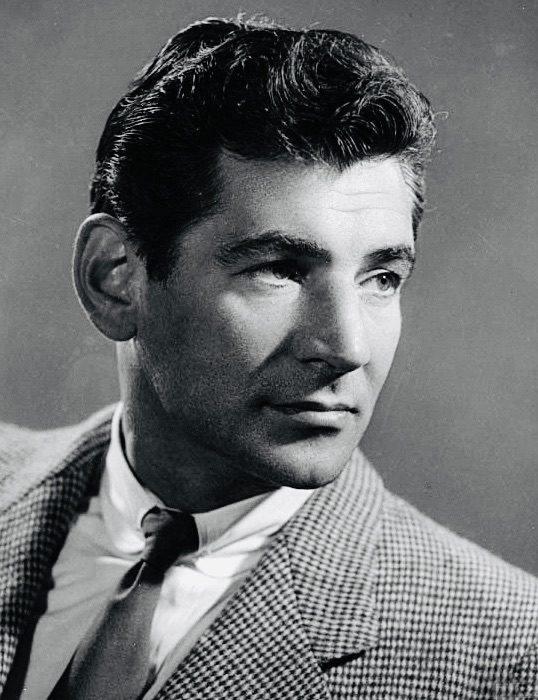

Rising to stardom in the early 1940s, Leonard Bernstein fulfilled his ambition of becoming the first great American conductor of a major symphony orchestra. He filled these big shoes in 1943, when, in a last-minute switch, he replaced the revered Bruno Walter as conductor of the New York Philharmonic in Carnegie Hall. He was only 25.

Bradley Cooper’s feature film, Maestro, begins at this crucial turning point in Bernstein’s storied career as a cultural icon. From that moment onward, he was the talk of the town, an enormously talented conductor and composer whose works would range from West Side Story to Candide.

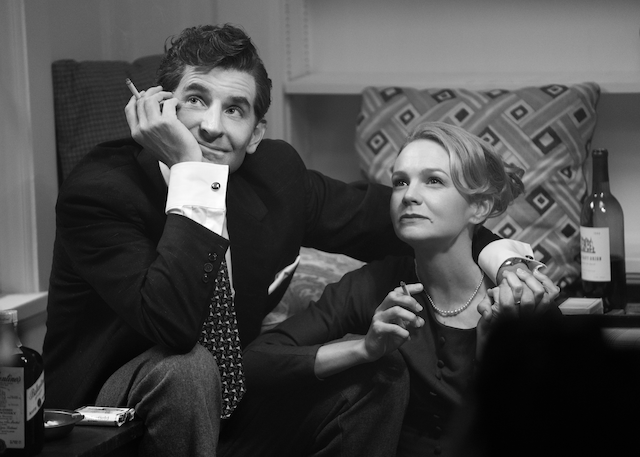

Now available on the Netflix streaming platform, Maestro is a full-bodied biopic of a force of nature. Cooper, in his dual role as director and actor, portrays Bernstein with unflagging vigor and charm. A cigarette almost always dangling from his lips, he was a serious musician as well as a social butterfly unconstrained by the social conventions of his day.

My wife, Etti, looked forward to this two-hour-and-eleven minute movie due to her indirect connection to Bernstein. In December 1963, when she was a teenager, Bernstein conducted the world premiere of his latest composition, Symphony No. 3, Kaddish, at the Mann Auditorium in Tel Aviv.

The Zadikoff Choir of Jaffa-Tel Aviv, of which she was a member, performed that evening. This long-forgotten event is preserved in a photograph of the choir and Bernstein that she treasures as a keepsake from her youth.

Sixty years on, Etti was naturally curious to see how Bernstein, who died in 1990 at 72, would be portrayed in Maestro. In short, he is a ball of fire, an extravagant bisexual hedonist and bon vivant drawn to drugs, never at a loss for words, and always smoking.

The movie focuses on his loving but tumultuous relationship with his wife, Felicia Cohn Montealegre, an actress of Jewish and Catholic ancestry who was born and raised in Costa Rica and who met Bernstein at a party in New York City in the 1950s.

It would appear that Bernstein, known as Lenny, was instantly attracted to Felicia, who is skillfully portrayed by Carey Mulligan in a passionate yet restrained performance. When she alludes to her mixed descent, he aptly describes it as “an interesting marriage of words.”

Despite his indisputable talents, Bernstein knew that, as a Jew, he faced a silent but formidable obstacle in a country where antisemitism was and still is no small matter. In a pivotal scene less than 30 minutes into the film, a seasoned European conductor/mentor strongly advises him to change his surname to Burns. “To a Bernstein, they will never give an orchestra,” he predicts glumly.

Flouting his friend’s well-meant advice, Bernstein, out of pride and self-respect, retains his Jewish-sounding last name, apparently secure in the knowledge that he can climb the greasy ladder of success without compromising himself. As if to underscore his defiance, he is later seen wearing a Harvard University jersey emblazoned with Hebrew letters.

A recurring theme in the film is Bernstein’s fondness for both sexes. As it opens, he rises from a bed, drumming his fingers rhythmically on the naked rear of an unidentified male companion. At another juncture, he meets a married male friend and his wife in a park, bends down to speak to their young daughter and says without missing a beat, “I’ve slept with both your parents.”

Inevitably, Felicia is fed up and crushed by Bernstein’s philandering. “If you’re not careful, you’ll die as a lonely old queen,” she warns him.

Bernstein’s sister, however, understands his sexual attraction to both men and women, saying he cannot “be only one thing.”

When one of his daughters asks him about rumors regarding his bisexuality, he lies, leaving it fester as an open wound that virtually poisons his otherwise affectionate bond with Felicia. But when she is fighting for her life after being diagnosed with lung cancer, he is there for her in body and soul.

Maestro, an animated and mostly enjoyable film that unfolds in stark black-and-white hues and in vivid colors, presents him as a person with a strong work ethic and as a perfectionist torn between his position as a conductor and a composer.

To the end, Bernstein was a man in motion, whether on the podium or outside the concert hall. And as he aged, his joie de vivre never diminished. “Summer still sings in me,” he murmurs toward the denouement, always ready to seize the day.