With the six major powers struggling to meet an end-of-June deadline for attaining a comprehensive and historic nuclear deal with Iran, two formidable issues remain to be settled — the timing of sanctions relief and the extent to which international monitors would have unrestricted rights to inspect Iran’s nuclear facilities.

Judging by the rhetoric emanating from both sides since a framework interim agreement was signed in Lausanne, Switzerland, last month, these unresolved problems may yet scuttle the prospects of a final accord.

Under the broad terms of last month’s interim accord, which is intended to drastically curb the Iranian nuclear program over a 15-year period, Iran’s existing facilities would be subjected to production limits and the number of its centrifuges to enrich uranium to low levels would be cut by two-thirds.

In exchange for these concessions, the crippling economic sanctions that have sharply reduced Iran’s ability to export oil and tap into the global bank system would be cancelled.

This interim agreement is clearly a step in the right direction, but if Iran and the major powers — the United States, Russia, China, Britain, France and Germany — fail to overcome their differences over these basic issues, there will be no comprehensive accord, with all its attendant consequences.

In the hope of achieving the best possible outcome for itself, Iran has been engaging in verbal brinkmanship.

Its supreme leader, the hardliner Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has demanded that sanctions be withdrawn at once after a final accord is signed and sealed. “The sanctions should be lifted on the same day of an agreement, not six months or one year later,” he declared.

Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif, Iran’s chief negotiator at the talks, has been just as emphatic. Unless sanctions end immediately, he warned, Iran would go ahead with its enrichment program “without any limitations.”

As for international inspections of Iranian nuclear sites, Khamenei has repeatedly declared they will not be opened to foreigners under any circumstances. Similarly, a senior commander of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard, General Hossein Salami, sarcastically said that inspectors would be allowed to visit these places only “in their dreams.”

U.S. President Barack Obama has defended a comprehensive agreement as a “once in a lifetime opportunity” to impose a cap on Iran’s nuclear ambitions. But he has vowed to reject a “bad deal.”

In line with this pledge, the United States has drawn a series of red lines regarding its expectations of what constitutes an acceptable final agreement.

John Kerry, the secretary of state, has said, “We will not sign a deal that does not close off Iran’s pathways to a bomb and that doesn’t give us the confidence that we will be able to know what Iran is doing and prevent them from getting a nuclear weapon.”

Furthermore, he went on to say, monitors must be able to inspect Iranian sites “every single day.”

Obama has said that sanctions will be lifted only after Iran lives up to its commitments. In a similar vein, Vice President Joe Biden has given Tehran notice that no agreement will be possible if Iran expects “total sanction relief or significant sanction relief” immediately after a comprehensive agreement comes into effect.

Jeff Rathke, a State Department spokesman, elaborated on this point: “The process of sanctions suspension or relief will only begin after Iran has completed its (obligations).” He also pointed out that the breakout time has been increased to at least a year, referring to the length of time Iran would require to assemble a nuclear device once the Iranian regime has decided to build one.

The U.S. position, he claimed, is consistent with what was agreed upon in Lausanne in April.

His colleague, Marie Harf, has put it more succinctly, “(Iran) will receive sanctions relief after (it) completes all of its nuclear related steps.”

Despite these bold assurances, Israel is extremely wary.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, having most recently compared Iran to Nazi Germany, has made denigrating references to the interim accord: “Not a single centrifuge (will be) destroyed. Not a single nuclear facility (will be) shut down … Thousands of centrifuges will keep spinning, enriching uranium. That’s a very bad deal.”

Calling for a “better” deal, Netanyahu believes it should consist of two components:

“First, instead of allowing Iran to preserve and develop its nuclear capabilities, a better deal would significantly roll back these capabilities…

“Second, instead of lifting the restrictions on Iran’s nuclear facilities and program at a fixed date, a better deal would link the lifting of these restrictions to an end of Iran’s aggression in the region, its world-wide terrorism and its threats to annihilate Israel.”

Israel is demanding that six addendums be attached to a comprehensive agreement: Iran’s stock of centrifuges should be reduced significantly. The Fordo uranium enrichment plant should be closed. Sanctions should be phased out gradually. The dimensions of Iran’s nuclear program should be fully disclosed. Iran’s stockpile of five percent enriched uranium should be shipped abroad. International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors should have access to Iranian nuclear sites at any time and at a moment’s notice.

It’s extremely unlikely that Iran would agree to such conditions. But Obama has said that he “respects” Israeli apprehensions and that Israel has “every right to be concerned about Iran,” a nation that has, he observed, threatened to destroy the Jewish state, denied the Holocaust and expressed “venomous antisemitic ideas.”

In his attempt to mollify Israel, Obama has promised to redouble support for Israel’s security. “I would consider it a failure on my part, a fundamental failure of my presidency, if on my watch, or as a consequence of work that I had done, Israel was rendered more vulnerable.”

Yesterday, Obama said that a comprehensive agreement is in Israel’s best interests. And he added, “The people of Israel must always know: America has its back.”

Wendy Sherman, the U.S. under secretary of state for political affairs and its lead negotiator at the nuclear talks, has acknowledged that while Israel’s concerns are legitimate, diplomacy is ultimately the only way to stop Iran from acquiring a nuclear arsenal.

In response to Netanyahu’s demand that a nuclear agreement should be contingent on Iranian recognition of Israel, Sherman has argued that such contentious issues must be addressed separately. “Getting the deal is difficult enough,” she explained. “Israel’s right to exist and Iran’s actions in the region will be dealt with on a parallel track.”

As for Sunni Arab concerns that a nuclear-armed Iran would pose a threat to their security, Obama has pledged that the United States will maintain a military presence in the Middle East and help Arab states deter aggression.

In concrete terms, the Obama administration is considering a number of options — a U.S. defence pact with Arab allies, joint U.S.-Arab military exercises, the designation of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates as non-NATO allies, and the sale of F-35 stealth fighter jets to certain Arab countries after Israel has taken delivery of them.

Apparently unimpressed by these considerations, Saudi Arabia has threatened to go nuclear. “Whatever the Iranians have, we will have, too,” warned the former Saudi director of intelligence, Prince Turki bin Faisal, at a conference in South Korea.

If Iran and the major powers fall short of reaching a final agreement, Washington would come under pressure to consider military means to ensure that Iran does not join the nuclear club, of which Israel is a member.

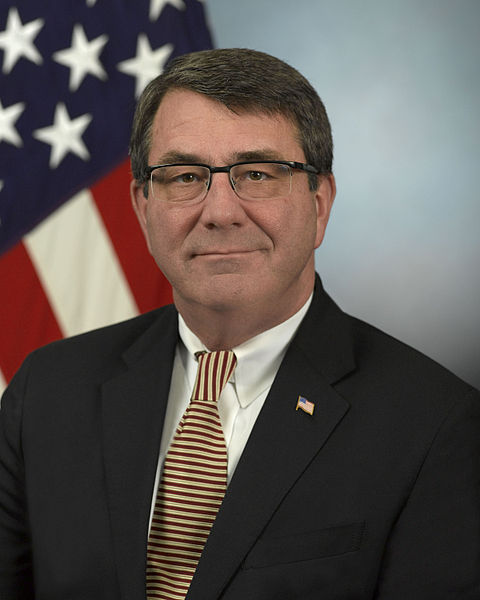

U.S. Secretary of Defence Ashton Carter has already warned Tehran that its bunker busting bombs could penetrate and destroy Iran’s subterranean nuclear installations. “We have the capability to shut down, set back and destroy the Iranian nuclear program,” he said on April 11. Carter quickly added that a negotiated agreement is preferable to war, since “military action is reversible over time.”

It’s doubtful whether the Obama administration would resort to military force to deal with Iran’s nuclear program. But with Iran having adopted a tough position on sanctions relief and foreign inspections of its nuclear sites, one must seriously wonder whether an accord is achievable.