Joseph Mitchell spent the greater part of his career at the intersection between journalism and creative writing. A reporter on the staff of The New Yorker for 58 years, he brought to his craft a boundless melange of curiosity, energy, observational powers and an understated, elegant prose style.

Born and bred in North Carolina, the son of a cotton and tobacco farmer, Mitchell found his subjects not in the far corners of the world but in the nooks and crannies of New York City. The New Yorkers he profiled were common folk, the salt of the earth, and his stories about them amplified the human condition.

“Mitchell seemed to prove the journalist’s adage that there is a story in anyone if only you take the time to listen,” writes Thomas Kunkel in his splendid biography, Man in Profile: Joseph Mitchell of The New Yorker (Random House). “In Mitchell’s hands, outwardly unremarkable people yielded remarkable tales, all conveyed with novelistic detail and the explorer’s sense of delight.”

Mitchell’s body of work was collected in a series of critically acclaimed books — My Ears Are Bent, McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon, Old Mr. Flood, The Bottom of the Harbor and Up in the Old Hotel. But much to his frustration and disappointment, he never managed to produce a magum opus, the “big book” about New York City that had been percolating in his mind for years.

And much to the puzzlement of his colleagues, editors and readers, Mitchell’s familiar byline virtually disappeared from the pages of The New Yorker from the mid-1940s until his death half a century later. He was not suffering from writer’s block, Kunkel claims. He simply did not finish anything.

Mitchell was drawn into journalism at the University of North Carolina, editing the student literary publication and writing short stories for it. And he contributed Sunday pieces to daily newspapers. In 1929, The New York Herald Tribune, one of the finest papers in the city, published his feature story on a tobacco market.

Emboldened by his success as a freelancer, he left the university several courses shy of a liberal arts degree. When he told his father he intended to be a journalist in New York City, he said, “Son, is that the best you can do, sticking your nose into other people’s business?”

In New York, Mitchell was introduced to the city editor of the Herald Tribune, the fellow Southerner Stanley Walker, who took a liking to him. Walker had no position to offer the young man, but in short order Mitchell was hired by The New York World as a copy boy. Fiercely ambitious, he was soon writing police stories and contributing features to the Sunday edition.

Shortly afterward, in the winter of 1930, Walker offered him a reporter’s job. Assigned to a beat in Harlem, he met a procession of flamboyant characters, from street preachers and speakeasy operators to drug dealers and prostitutes. They left an immense and lasting impression on him.

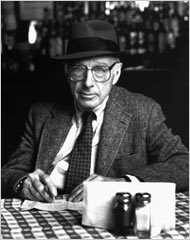

In accordance with Walker’s sage advice, he dressed fastidiously, buying Brooks Brothers attire, and walked everywhere, picking up an extraordinary feel for New York’s neighborhoods. These were habits that with stay with him for the rest of his life.

By 1931, Mitchell was cranking our features running the gamut from color stories to celebrity profiles. These early pieces, Kunkel notes, demonstrated his aptitude for dialogue.

“Like all young reporters, Mitchell was intoxicated by the romance of newspapering in New York,” writes Kunkel. “He loved the fact that every day brought a new, unexpected assignment. He thrilled when the newspaper’s huge presses rumbled to life, shaking the building and tingling the nerves. He loved the camaraderie of the newsroom and of the smoky newspaper bars to which Mitchell and his colleagues reflexively retired after work.”

Eager to expand his professional horizons, Mitchell sought to branch out into magazine journalism. Thanks to a colleague and fellow North Carolinian who had become an editor at The New Yorker, a fairly new publication, Mitchell contributed his first piece to that magazine in 1933, a short Talk of the Town item about a silk hat manufacturer. Several months later, The New Yorker accepted a longer article from him on a town in Pennsylvania where quickie marriages were performed. He quickly followed that up with a profile on a popular singer.

The long form magazine format appealed to Mitchell, who longed to write more substantive pieces. Certainly, the editor of The New Yorker, Harold Ross, appreciated Mitchell’s ability to turn a phrase and his eye for telling detail.

Mitchell reported for work at The New Yorker in 1938. He would be paid $100 a week, slightly more than he had been earning at The New York Herald Tribune. He got off to a scintillating start, producing 13 pieces, plus a few Talk of the Town contributions, in 1939. He wrote his stories on an Underwood typewriter, which he would use until his death.

By 1940, his pace had slowed to a virtual crawl, Kunkel says. “Mitchell began to modulate his manic production, putting more time into his reporting and letting the stories get progressively lengthier and more layered.”

Elaborating on this point, Kunkel explains that Mitchell’s stories were now more technically demanding and harder to write. “Mitchell was further burdened by a strain of perfectionism as compulsive as any other aspect of his personality.”

When he finally turned in a story, it was flawless. “I’d insert maybe three commas,” one of his editors recalled.

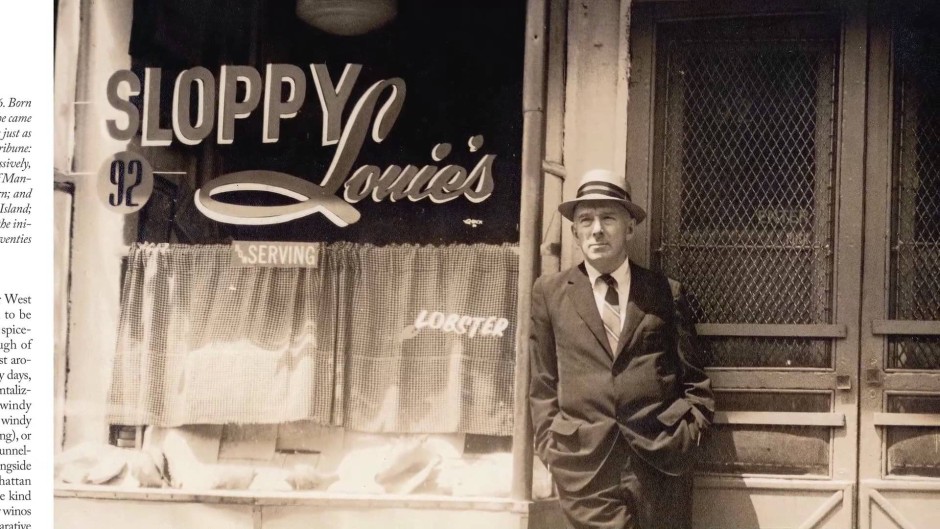

Eschewing the commonplace with respect to topics, Mitchell had a nose for the unusual, as Kunkel suggests. His droll piece on New York’s rat infestation, Thirty-Two Rats from Casablanca, captivated his upper-crust readers, and his delightful articles on a Fulton Fish Market character and the leader of the city’s Roma community charmed them as well.

Interestingly enough, the profiles were composites, a practice frowned upon today but perfectly legitimate back in Mitchell’s day.

Kunkel goes on at length about another contentious issue — Mitchell’s salary. From 1945 onward, Mitchell — the father of two daughters — earned $115 per week. Privately, he groused about his pay. It was raised by $25 a week in 1953 and would remain the same for the next 11 years. In today’s dollars, he earned $60,000 per annum.

Despite this grievance, Mitchell enjoyed cordial relations with the magazine’s editors.

Harold Ross’ successor, William Shawn, was just as respectful of Mitchell’s talent and provided him with the encouragement and flexibility he required to pursue unconventional subjects. Shawn, who also tolerated his minute output, raised his salary to just under $300 a week in the early 1970s.

Shawn’s successors, Robert Gottlieb and Tina Brown, attempted to coax him out of his writing slump, but they failed.

Mitchell died on May 24, 1996 at the age of 87, prompting The New Yorker to run a six-page spread on him. “He was an essential figure in modern writing and in the history of the city,” the tribute observed.

Kunkel agrees with that assessment, and in Man in Profile, he delivers a first-rate portrait of one of America’s greatest journalists.