The Holocaust unfolded along two broad trajectories. In western and central Europe, Jews were deported to Nazi extermination camps in Poland, while in Soviet republics like Ukraine and Lithuania, they were usually murdered in mass shootings. While the deportations were often carried out in secret or at least discreetly, the executions took place in public, in full view of the victims’ neighbors.

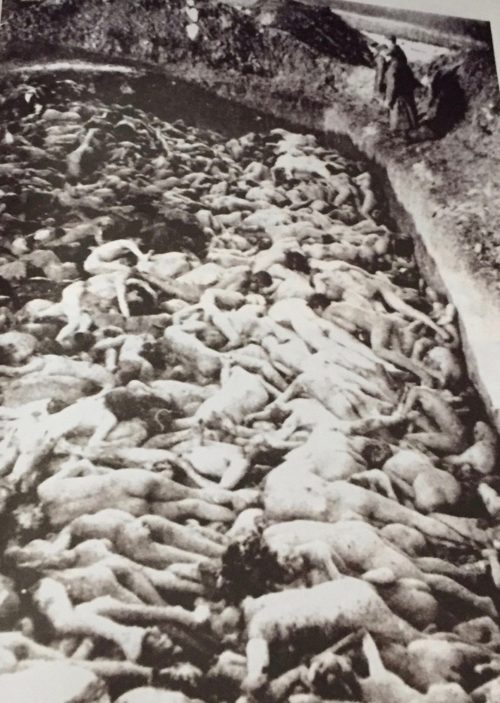

It’s estimated that, of the 2.2 million Jews killed within the present-day boundaries of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine between 1941 and 1944, more than 80 percent were shot by firing squads manned by Germans and local collaborators.

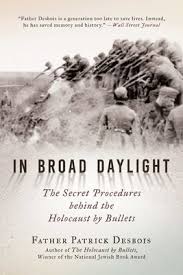

And yet, as Father Patrick Desbois writes in his chilling book, In Broad Daylight: The Secret Procedures Behind the Holocaust by Bullets (Arcade Publishing), the crimes they so callously committed from the predawn hours well into the night “remain little known to the general public.” Desbois’ objective is to shed light on this relatively little-known aspect of the Holocaust.

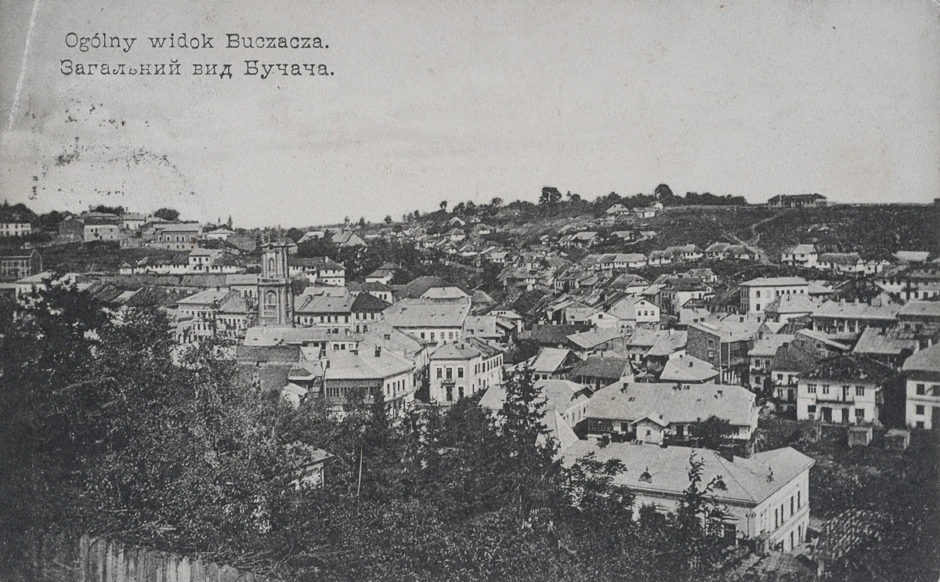

Another riveting book under review, Anatomy of a Genocide: The Life and Death of a Town Called Buczacz (Simon & Schuster), by Omer Bartov, focuses on the campaign of ethnic cleansing that virtually eradicated the Jewish population of a Galician Polish town that today is part of Ukraine. The murderers were German and Ukrainian policemen. All too often, Bartov observes, the Ukrainian killers were neighbors, even friends, of the Jewish victims.

Soviet citizens of German ancestry, known as Volksdeutsche, were sometimes involved in the shootings, says Desbois, who heads an organization dedicated to documenting the evidence of the Holocaust in Eastern Europe. In Transnistria, for example, ethnic Germans were recruited to carry out these gruesome tasks. Gregory, a witness cited by Desbois, says the murderers were not professional criminals, but peasants who killed Jews with “boundless brutality.” In some instances, Jewish women were gang raped before being shot.

Desbois cites a litany of murders that occurred in the presence of local witnesses.

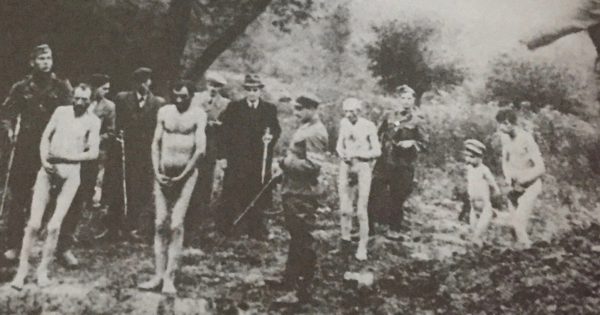

In Novogrudok, a town southwest of Minsk, the Jewish inhabitants were routed from the Nazi ghetto and assembled in the main square. Loaded into trucks, they were taken to a nearby village, forced to undress, shot and buried in mass graves. Further afield, in Slonim, 10,000 Jews were summarily shot. Escapees were turned in by locals and immediately executed.

The slaughter of Jews in the Ukrainian town of Drogobytch was efficiently organized. Some guards were in charge of keeping watch over Jews. Others accompanied the trucks to the site of the shooting. Still others waited at the ditch where their bodies would be dumped.

Jews were also murdered in Medzhybizh, where the tomb of the legendary Baal Shem Tov is located. Desbois interviewed Olga, who was a girl when this event transpired. “The Jews walked calmly,” she recalled. “But there was a sense of worry in the air.”

Ostap Hucalo, the Ukrainian mayor of the small town of Bolekhov, near the city of Ivano-Frankivsk, told Desbois about the massacre of 2,000 Jews: “A board had been placed over the ditch on which Jews had to go naked. I still remember that the Jewish families held hands on the plank. Then they were shot in the head from behind and then they fell into the ditch. There were a few Jews down in the ditch who had to lay the dead bodies in rows.”

In yet another Ukrainian town, Doubrivska, Jews had to dance in front of townspeople before being shot. “There were quite a few mixed families,” says Maria, a witness. “A lot of Polish and Ukrainian women were married to Jews and had children with them. These women got favorable treatment and nobody harmed them, but the children of mixed couples were considered Jews and were exterminated.”

Desbois’ description of the Babi Yar ravine massacre in Kiev is brief and affecting: “As they approached the valley, the Jews went through a barricade, manned by the Germans … Then they had to leave their baggage , their jewels, their clothing. Every Jew — man, woman, child –was murdered by a person armed with a gun. More than 30,000 victims saw their killers, while each killer looked into the eyes of his Jewish victims. In broad daylight. Thirty thousand personal crimes.”

Unlike the murderous rampage in Babi Yar, the killing of 27,000 civilians, mostly Jews, in the central Russian city of Rostov-on-Don is still largely unknown. Desbois says the Germans forced Russian civilians to watch the shootings to dissuade them from joining anti-Nazi partisan forces.

Sifting through German archives, Desbois stumbled upon the deposition of Edith D., an ethnic German school teacher who witnessed a mass shooting in Kamianka-Bouzka.

“One day, from the school yard, I heard a horrible shriek,” she said. “The children could watch the execution process from the yard. We realized that a crowd of Jewish women and children were gathered on the land bordering the yard. Ditches had been dug on this land, and they were supposed be for building bunkers. The group of women and children were guarded by SS men. The victims had to get completely undressed and were then taken in groups of six and eight two the edge of the ditches and shot … This was where the shriek I spoke of came from. ”

Desbois’ commentary is succinct: “It is barely believable, barely comprehensible, that an execution would be planned next to a German primary school. Unbelievable that the killers didn’t ask for the school to close. Also unbelievable that the children and their teacher watched as though unable to tear themselves away from the spectacle of the murder of Jews.”

Jews who managed to hide during a massacre were vulnerable. In Yavoriv, a Jewish family — a couple and their daughter — found shelter with Christians, but they were betrayed. “The people hiding them denounced them. When the Germans went to get them, the girl took poison that her father had given her and died, but the mother didn’t have time to take the poison.”

When a German policeman in the village of Sdolbunov found a small Jewish boy in the arms of an old woman, he grabbed the child by the legs, swung him around several times and then hit his head against the doorpost. “It sounded like an exploding tire,” Desbois writes.

Bartov, a professor of history at Brown University, has a special interest in Buczacz because his mother was raised there. He spent two decades gathering material for his book.

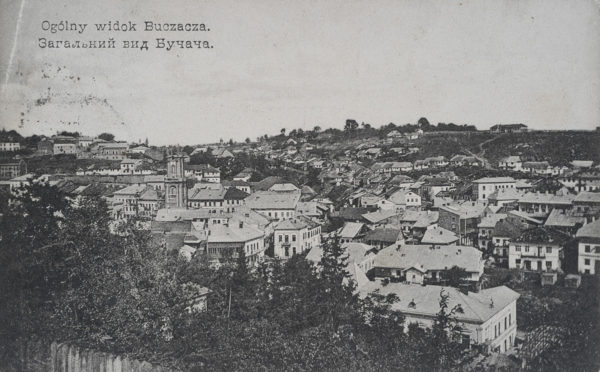

Jews, Ukrainians and Poles lived side by side there for centuries. So when genocide struck, it was both cruel and intimate, “filled with gratuitous violence and betrayal as well as flashes of altruism and kindness.”

The traditional economic role that Jews performed, a product of the feudal system, created animus against them. As Bartov puts it, “Jewish moneylenders, shop and tavern keepers, cattle dealers, estate and mill leasers and owners were all presented as fleecing the ignorant peasants, tricking them into alcohol and tobacco addiction, lending them money at cutthroat rates and retarding (their) development.”

On the eve of World War I, he adds, Jews owned 10 percent of the estates, comprised 20 percent of the landowners, and made up more than 50 percent of the property leaseholders in Galicia. The vast majority of Jews, however, were poor. Many of these Jews emigrated before the Holocaust.

With the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire on October 31, 1918, Poles and Ukrainians fought for dominance. This placed Jews in an awkward position due to the Polish belief that Jews preferred Austrian rule to Polish independence.

Polish troops captured Buczacz in June 1919. A few days later, Ukrainian forces ousted them, only to be pushed back again by the Poles, who proceeded to plunder property and ignite pogroms. A war pitting Poland against the Soviet Union broke out in the summer of 1920, bringing Buczacz under temporary Bolshevik rule until Poland finally prevailed.

By then, 50 percent of Buczacz’s population was Jewish. Poles and Ukrainians respectively comprised 30 percent and 20 percent of its residents.

Nevertheless, Jews were a group that neither the majority Poles nor the minority Ukrainians could truly accept. In general, Poles regarded Jews as an alien, unassimilable and potentially subversive element.

“Jews could be ignored, tolerated or expelled, but by the nature of the nationalism that had evolved in this region, they could neither be recognized as a separate indigenous national group nor assimilated as ethnically kindred,” says Bartov. “And as a supposedly protected and allegedly privileged minority, the Jews were seen as undermining the very core of Polish nationalism.”

At the end of the day, he notes, Poles and Ukrainians increasingly felt that Jews were their enemy’s friend, which meant that Jews were susceptible to economic boycotts and even violence.

By contrast, Poles regarded Ukrainians as fellow Slavs and Christians who could be integrated into Polish society. Ukrainian nationalists, though, were more interested in liberating themselves from Polish rule than in living in a Polish state. Indeed, Ukrainian irredentists looked to Adolf Hitler as the only European leader who could bring them national independence, with the result that some Ukrainians would join a Ukrainian Waffen SS division.

There was an uptick of anti-Jewish feeling in both Polish and Ukrainian societies following the death of Jozef Pilsudski, Poland’s supreme leader, in 1935. The new Polish government, known as the Camp of National Unity, was officially opposed to antisemitic violence, but portrayed Jewish citizens as a separate national group and maintained that the “Jewish question” could be solved only by emigration.

The Soviet occupation of eastern Poland in 1939 would become a fraught issue for Jews, Poles and Ukrainians. Most Poles and Ukrainians, Bartov notes, perceived Jews as beneficiaries of Soviet rule. And while some Jews in such towns as Buczacz did not mourn the demise of Poland, they saw few advantages in the Soviet presence. “Many Jews recalled it as a period of oppression, denial of rights, loss of property, and profound uncertainty about the future,” he says.

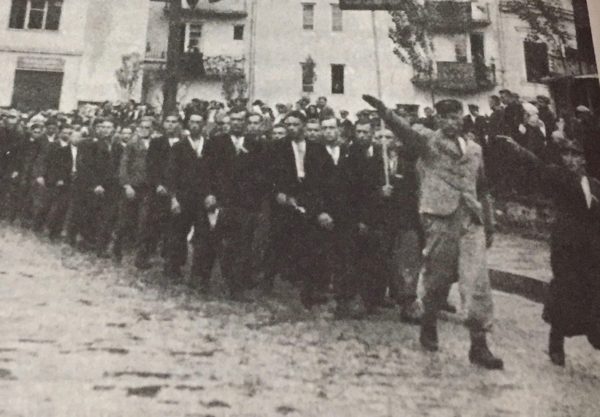

The German army rolled into Buczacz on July 4, 1941, roughly two weeks after Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. On the first night of the occupation, German soldiers, accompanied by Ukrainian hooligans, broke into Jewish homes and raped Jewish girls. Jewish men, forced into labor battalions, were subjected to severe beatings, forced to wear armbands with a blue Star of David and banned from main streets. Wealthy Jews were compelled to pay huge ransoms.

From 1941 onwards, the Germans, assisted by Ukrainians, murdered approximately 60,000 Jews in the region around Buczacz. Well over 10,000 Jews in Buczacz were shot or deported to the Belzec concentration camp. “The Jews were hunted on the streets like rabbits,” a Polish woman said.

Jews who went into hiding were hunted down relentlessly. When the Red Army reoccupied Buczacz, fewer than 100 Jews were still alive in the general vicinity.

The German most clearly associated with these murders, Kurt Kollner, had been a car rental dealer from Saxony who was considered a reliable and socially respectable businessman and whose father had belonged to the Social Democratic Party in Germany. “One reason for Kollner’s success in implementing local genocide was his knack for getting to know the victims before organizing their murder,” says Bartov. “Rather than employing dehumanization and detachment, he used trust, familiarity and false promises, which made things much smoother and provided grater opportunities for personal enrichment.”

Risking life and limb, compassionate Christians aided Jews without any thought of profit. Even some perpetrators, including German administrative officials and two Wehrmacht officers, spared Jewish lives in “capricious acts of goodness in the midst of slaughter.”

“Yet the memory of goodness cannot erase the horror enabled and perpetrated by the callous indifference, gratuitous violence and homicidal avarice of neighbors,” he adds.

Of course, Jews were not the sole victims. In 1944, Poles in the region were ethnically cleansed by radical Ukrainian nationalists. Bartov estimates that one-third of the Buczacz district’s pre-war population was lost through killing, deportation, expulsion or flight.

Population exchanges in the wake of the war changed the demographics of the region. About 500,000 Poles were removed from eastern Galicia, which was incorporated into the Ukraine, while more than 500,000 Ukrainians were deported from Poland. “As a result of genocide, ethnic cleansing and population policies, these once multiethnic lands had become almost completely homogeneous,” he says.

Such was the horrific toll the war took on this remote and bloodied corner of Europe.