The publication of a new, annotated edition of Adolf Hitler’s incendiary manifesto, Mein Kampf (My Struggle), has set off a passionate debate in Germany that forces it to face its ugly past yet again.

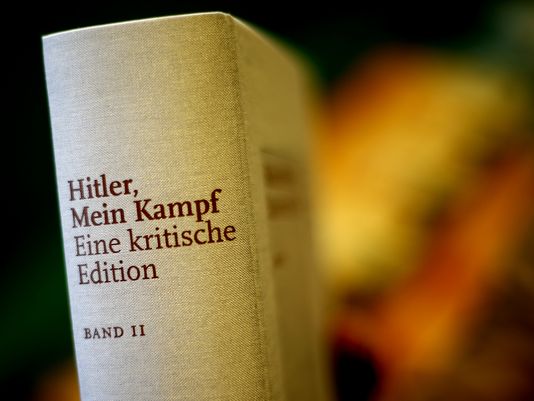

The nearly 2,000-page book, replete with some 3,500 annotations, is supposed to immunize readers from misusing or exploiting its horrific contents and help eradicate its cult status.

Those who think it should be republished argue that it cannot be suppressed indefinitely, however crazed, half-baked, muddled and turgid it may be. Critics fear that its reappearance may legitimize, even elevate, an unbalanced, racist screed that became one of the intellectual pillars of a genocidal regime hellbent on murdering Jews.

As a child of Holocaust survivors whose lives were torn asunder by Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland, I empathize with those who fervently believe it should continue to be banned.

Hitler’s warped ideas about racial superiority, national destiny and the imperative of dictatorship coalesced into a toxic brew, an ethnocentric and violent ideology that mobilized the masses. Hitler refined and glorified the concept of an Aryan master race, marginalized and demonized Jews and provided the rationale for Germany’s unbridled aggression in Europe.

As the German historian Eberhard Jäckl has written, “Perhaps never in history did a ruler write down before he came to power what he was to do afterwards as precisely as Adolf Hitler.”

Given these factors, I most certainly would have opposed the reissue of Mein Kampf had annotations not been inserted. An unexpurgated version would have been a horrible affront to Holocaust survivors and their children and relatives, as well an insult to decent Germans.

The publisher of the new edition, the Munich-based Institute of Contemporary History, had no such intention, of course, and this is why I support its project, one major misgiving notwithstanding.

In anticipation of the expiry of the 70-year copyright on Mein Kampf, held by the German state of Bavaria until January 1, 2016, the institute assembled a team of five top-notch historians to deconstruct it by means of informed notes alongside Hitler’s rambling rants.

As the institute’s director, Andreas Wirsching, said, “It would (have been) completely irresponsible to allow this jumble of inhumanity to be released to the public domain without commentary, without countering it through critical references that put the text and its author in their place.”

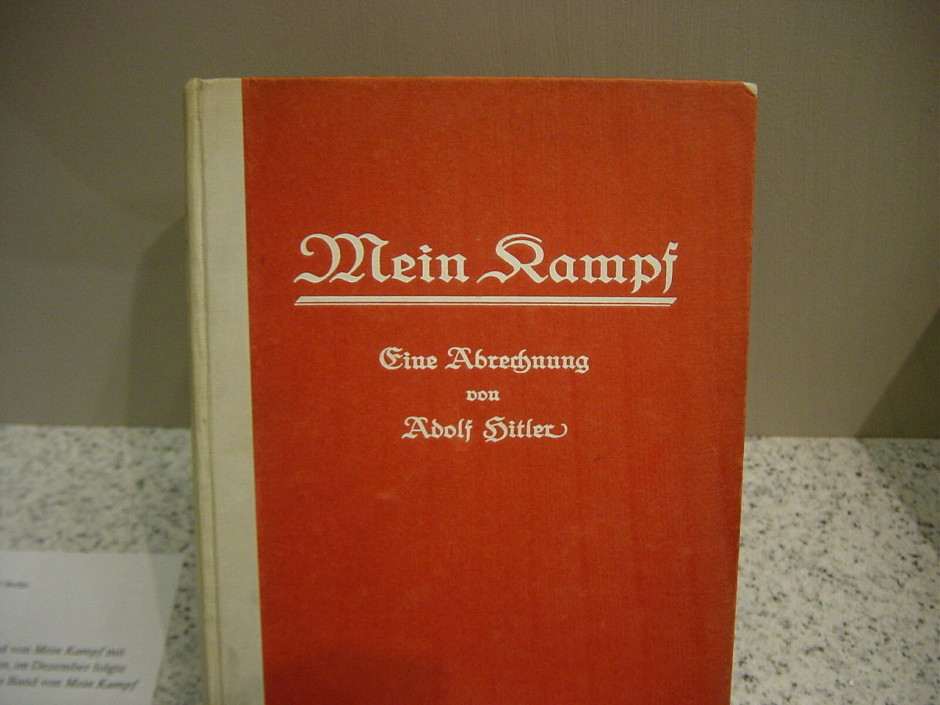

Hitler, a failed artist and a veteran of World War I, wrote Mein Kampf after being arrested for his pivotal role in the 1923 Beer Hall putsch in Munich. While in Landsberg prison, Hitler dictated it to his acolyte, Rudolf Hess. It was published in two volumes in 1925 and 1927, when the Nazi Party was still struggling to be taken seriously.

Sales of Mein Kampf picked up considerably after Hitler’s accession to power in 1933. Newly married couples in Germany were required to buy it and students were bombarded by it. Twelve million copies had been sold by 1945, when the Third Reich went down to ignominious defeat at the hands of the Allies. Mein Kampf, last published toward the close of World War II, was a best-seller that made Hitler a wealthy man.

It goes without saying that Mein Kampf was partially instrumental in poisoning the mind of a great nation. It brainwashing tens of millions of Germans into succumbing to the misguided belief that the “Jewish peril” endangered their country and that Germany had an inherent right of conquest and plunder throughout Europe.

In short, Mein Kampf was one of the most intellectually destructive books in the annals of mankind.

It is no wonder that the Allies placed a ban on it after occupying Germany. Yet Mein Kampf never really disappeared. German neo-Nazis fawned over previously published editions. And elsewhere, including the Arab world, Nazi sympathizers read contraband or online versions to their heart’s content.

In postwar German schools, students studied annotated excerpts of Mein Kampf as part of their history lessons. How could it be otherwise? Could teachers explain the rise and development of Nazi Germany, plus the dangers of political extremism, without directly referring to it? Not really.

“Schools cannot ignore Mein Kampf,” says the president of the German Association of Teachers, Josef Kraus.

I agree.

But I’m left with one nagging problem.

The expiration of Bavaria’s copyright on Mein Kampf technically means it can be published without annotations by unscrupulous or antisemitic publishers. My hope is that most publishers will act honorably and insert appropriate annotations. The Institute of Contemporary History in Munich has certainly set a good example that should be followed.

Mein Kampf is a hateful book worthy of the trash can. Nonetheless, it’s also a work of historic importance that should be read. Which is why it shouldn’t be mindlessly suppressed.