Forty five years ago, Israel’s ambassador to the United States, Yitzhak Rabin, delivered a pep talk to a group of Jewish American teens in Washington, D.C. After he had finished speaking, Rabin — the future prime minister of Israel — gave 15-year-old Michael Bornstein of West Orange, New Jersey, a perfunctory handshake. Bornstein, a fervent Zionist who would settle in Israel in 1979, made a silent vow. “That is what I’ll be someday — Israel’s ambassador to America.”

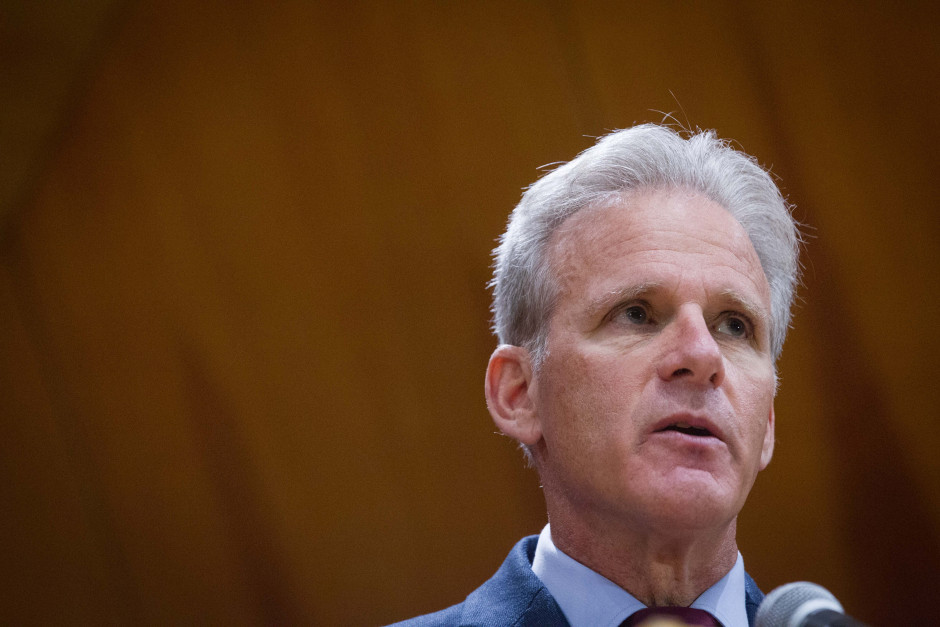

Thirty nine years later, a black limousine pulled up to the White House and out stepped the new Israeli envoy to the United States, Michael Oren, whose previous surname had been Bornstein. Oren, who had been appointed by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, had arrived to present his credentials to America’s new president, Barack Obama.

For the next four years, Oren — a reputable historian who has written the definitive work on the 1967 Six Day War — would represent his adopted homeland in the country of his birth. Tasked with preserving Israel’s strategic alliance with the United States, Oren frequently found himself in the vortex of the bitter disputes that soured Netanyahu’s relationship with Obama. These usually turned on the Arab-Israeli peace process and Iran’s quest for nuclear arms, both of which are hot-button issues in Washington and Jerusalem.

Oren recalls his stormy ambassadorship in Ally: My Journey Across the American-Israeli Divide, published by Random House. A vivid and lucid account about Middle East politics and diplomacy, it’s also a frank memoir about a young man’s decision to uproot himself and live out his Zionist dream in Israel.

Oren’s love affair with Israel was a function of his admiration for a nation that had resurrected itself and rooted in his anger over the bigotry that he faced as an American Jew.

“I had a keen sense of history, an awareness that I was not just a lone Jew living in late 1960s America, but part of a global Jewish collective stretching back millennia,” he writes.

But having been victimized by antisemitic bullying, Oren viewed himself as an outsider. “Being Jewish in America, while culturally and materially comfortable, felt to me like living in the margins,” he says by way of explaining why he joined the Zionist youth movement that brought him to Washington in May 1970 to meet Rabin in a memorable encounter.

Following his immigration to Israel, Oren fought in Lebanon with the Israeli army during the 1982 war and then studied Middle Eastern history at Princeton University. His pro-Israel views, he claims, cost him dearly. Publishers rejected his books, precluding an academic career. Rejected by academia, he managed a major software company and ghost wrote for Abba Eban, Israel’s former foreign minister. When these gigs ended, he was unemployed. Barely able to support his family, he considered leaving Israel.

Oren’s luck changed after he secured a post in Rabin’s office as an advisor on inter-religious affairs and wrote Six Days of War: June 1967 and the Making of the Modern Middle East. “The book,” he says, “was a life-changer.” He became a television commentator, an op-ed contributor, a fellow at the Shalem Center in Jerusalem and a visiting professor at Ivy League universities.

Oren met Netanyahu in 1983, when he was deputy chief of mission at the Israeli embassy in Washington. Although discomfited by Netanyahu’s harsh criticism of Rabin before his assassination, he respected his military and policy-making acumen and his resilience in bouncing back from an election defeat in 1999 at the hands of the Labor Party.

“Yes, I disagreed with some of Netanyahu’s positions on the peace process … but I believed that Netanyahu, like Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon before him, could adapt to changing political realities. After all, Netanyahu was the last Israeli leader to sign an agreement with the Palestinians — at the Wye River Plantation in 1998.”

Oren, the author of a best-seller on America’s historic role in the Middle East, took up his post with the hope of solidifying ties with the United States, Israel’s best friend and chief patron. “In America, Israel has an immensely generous source of diplomatic support and annual defence aid,” he writes. “In Israel, the United States has a stable, loyal and militarily proficient asset — a scientific and technological powerhouse — and a pro-American island in an often toxic sea.”

Yet Oren was under no illusions. Both countries had changed since the 1970s and were in danger of “drifting apart,” he points out.

Obama was animated by three gut Middle East causes — creating a Palestinian state, reconciling with Islam and preventing nuclear proliferation. “All three intersected with Israel’s interests, (but) in potentially abrasive ways.”

Claiming that the Obama administration was influenced by Edward Said’s anti-imperialist book, Orientalism, Oren says that a notion had taken hold in elite American circles that the United States was required to forge a rapprochement with Islam and distance itself from Israel.

By all accounts, Netanyahu’s first meeting with Obama went smoothly, but Oren later learned that Obama had demanded a full settlement freeze in the West Bank and in eastern Jerusalem, which Israel annexed in 1967.

Although Netanyahu balked at the idea, he would agree to a partial freeze and endorse a two-state solution. “But such concessions were too much to expect of the newly elected leader of Likud,” says Oren in a sharp critique of Obama’s policy. At another point in Ally, Oren apologetically claims that freezing settlements and stopping construction in Jerusalem “were small crosses that could cost (Netanyahu) an election well before he faced the biggest cross of all, creating a Palestinian state.”

This hard-line observation notwithstanding, Oren hews to a centrist view of the settlements and the land-for-peace formula. Some settlements, he notes, have been of “questionable strategic and diplomatic value” because they will not contribute to the preservation of Israel’s democratic and Jewish character. But Israel cannot afford to relinquish areas of the West Bank close to Israeli cities and industrial centers, he maintains.

He is critical of Obama’s disavowal of a letter President George W. Bush sent to Prime Minister Ariel Sharon in 2004 in which he said it would be “unrealistic” for Israel to return to the armistice lines of 1949. As Oren puts it, “For the first time in the history of the U.S.-Israeli alliance, the White House denied the validity of a previous presidential commitment.”

Oren takes Obama to task for having jettisoned what he says have been three “time-honoured” principles of the United States’ relationship with Israel — “no daylight,” or differences, between the two countries, “no surprises” foisted upon Israel by Washington, and no public spats between the allies.

Oren’s principles, in fact, are a figment of his imagination. Certainly, Israel and the United States have publicly disagreed on a wide variety of contentious issues, particularly over Israel’s occupation of the West Bank, its annexation of East Jerusalem and its insistence on building much of the security barrier inside the West Bank.

Though he comes down hard on some of Obama’s policies, Oren is convinced that the U.S. president is genuinely committed to Israel’s security. Yet he points out that Obama’s commitment to Israel’s wellbeing helps him realize his vision of a new Middle East. “By highlighting its contributions to Israel’s defence, the administration could justify pressuring Israeli leaders on peace,” he says.

Judging by his own words, Oren’s endorsement of a two-state solution seems tenuous. He doubts whether any Palestinian leader would be willing or able “to sign on to one.” And he supports the need for “a prolonged Israel Defence Force presence in sensitive parts of the West Bank” after a Palestinian state is established. Further, Oren is skeptical that Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas will ever be “a serious partner for peace.”

Oren, nonetheless, believes that Israel should have “shown more openness” to the 2002 Arab League peace plan, which broadly calls for a full Israeli withdrawal from the occupied territories in exchange for Arab recognition of Israel’s existence. But like a succession of Israeli prime ministers who have accepted only parts of the Arab initiative, Oren blithely advises Israel to ignore its key demand for a withdrawal to the pre-1967 frontiers. In this connection, he reports that Netanyahu was furious with Obama’s formula that “the borders of Israel and Palestine should be based on the 1967 lines with mutually agreed (territorial) swaps.”

The Iranian nuclear issue, of course, figures prominently in Ally. “Iranian nuclearization,” he observes, is “our generation’s paramount challenge.” He adds, “The differences I had with Netanyahu on the peace process and other issues paled beside our common conviction on Iran.”

Writing long before Iran and the six major powers signed an agreement in Vienna earlier this month, Oren says that “the original goal of eliminating Iran’s nuclear program had been supplanted by an arrangement that actually preserved it.” Oren, however, thinks that Netanyahu erred in lambasting the administration’s Iran policy before the U.S. Congress last March.

According to Oren, the Obama administration “quashed any military option” that Israel had considered using against Iran.

On another topic, Oren suggests that the United States was wrong to abandon Hosni Mubarak, the president of Egypt, during the Arab Spring rebellion in 2011. “Flagrantly brutal and corrupt, Mubarak was nevertheless America’s loyal friend for more than thirty years … That single act of betrayal … contrasted jarringly with Obama’s earlier refusal to support the Green Revolution against the hostile regime in Iran.”

Turning to a different subject, Oren acknowledges that American Jews feel increasingly “isolated and embarrassed” by Israel’s image as “a warlike and intolerant state.” He disagrees with this characterization, but concedes that Israel’s rule over Palestinians in the West Bank is a gnawing problem.

On a more personal note, he admits that “the daunting physical demands” and “the emotional and psychological strains of coping with virtually relentless tensions” between “the two countries I love” prompted him to ask himself whether he could continue being ambassador.

Toward the close of Ally, he returns to that theme. “I was often frustrated, exasperated and stressed, but not for a second did I feel anything less than fulfilled. And I was never bored.”

Currently a member of the Knesset for the right-of-center Kulanu Party, Oren explains why he ran for public office. “I knew that I wanted to keep serving Israel and believed that I could bring all that I had learned and experienced to bear. And at a time when Israel faced fateful challenges, how could I stand aside?”

It remains to be seen what contributions Oren can make as a politician. But I’m certain he will eventually write a book about his time in the Knesset, and I look forward to it. Oren is a fine writer and a skilled analyst, whatever you may think of his political views.