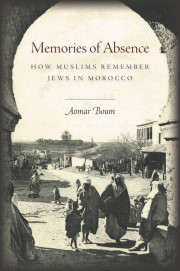

Aomar Boum, a Moroccan ethnographer, has written a rigorous, refreshingly candid account of one of the oldest Jewish communities in the Arab world.

Memories of Absence: How Muslims Remember Jews in Morocco, published by Stanford University Press, is something of a rarity in this field. As he writes in the introduction,“Although a few scholars have begun to revisit and reexamine the histories and lives of ethnic and religious minorities in the region, the place of religious minorities and of Jews in particular in this history has largely been ignored. Especially for native Muslim anthropologists, research on Middle Eastern Jewry and Judaism is still taboo.”

For Boum, a University of Arizona professor, the reason for this is clear: “Scholars can be labelled and stigmatized as pro-Zionist just for conducting research on the Jews of the Arab world, and this labelling can have serious professional and personal consequences.”

In Morocco, however, scholars drawn to Jewish studies are not necessarily marginalized, says Boum, a black Moroccan Muslim who was born and raised in a southeastern oasis where Jews once lived. Moroccan academics have written about Muslim-Jewish relations before and after the advent of Morocco’s independence.

In Memories of Absence, Boum examines both periods through four successive generations of 80 Muslim men in southeastern Morocco. “While members of the older generation express nostalgic sadness about the absence of Jews from Morocco, younger subjects use humor, jokes, heresay and mockery to protest, ostracize, demonize and resist Israelis and Jews in general, whom they see as their political and social enemies,” he concludes. “Laughter and derision serve as fuel for the perceptions, especially for those of the generation that have never met a Jew, that Jews are political spies and religious inferiors to Muslims.”

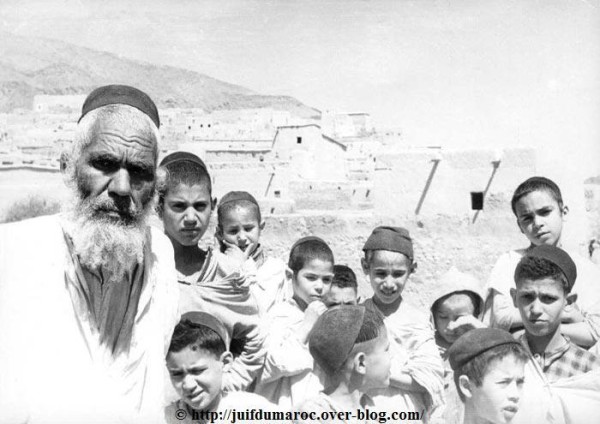

Boum focuses his attention on Akka, a town which had one of the most important Jewish communities on the fringes of the Sahara Desert. “As peddlers, metalworkers and saddlemakers, the Jews of Akka and other communities throughout the Anti-Atlas (mountains) played an active role in the tribal economy,” he says.

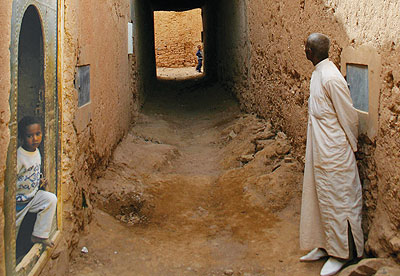

When Boum arrived in Akka in 2004 to conduct field work, the Jews had been gone for more than 40 years. “I wish the Jews had never left,” said Boum’s guide. “They added yeast to this economy.” Hajj Najm Lahrash, one of the richest notables in the region, echoed this sentiment: “We needed Jews for our economic survival. They depended on us for their personal security. We had to coexist to endure the desert.”

Approximately 2,000 Jews resided in Akka and surrounding villages in 1948, living in separate neighborhoods but among Berbers and Arabs. Although the Jews found themselves in one of the remotest corners or Morocco, they maintained contact with Jews in Palestine and throughout the Mediterranean basin, for both trading purposes and religious reasons, Boum notes.

During the 20th century, a variety of factors impelled the Jews of Akka to emigrate. “Jews left for many reasons, economic, political, personal and religious,” says an oldtimer. “But many left because we failed as nationalists to incorporate them, even though we claim the contrary.”

The Six Day War was a decisive moment. As Boum puts it, “The Arab defeat in 1967 led to a rise of anti-Jewish feelings and a culture of mistrust and intolerance among the Muslims. Despite the efforts of the national Moroccan Arab and Jewish leaderships … to guarantee the security of Jews in the new Moroccan nation-state, the Moroccan commitment to the Palestinian cause and (Morocco’s) membership in the Arab League made Jewish emigration inevitable.”

Although the Six Day War was a watershed, the birth of Israel in 1948 really launched this process of mutual estrangement. In May of that year, King Mohammed V called on Moroccan Muslims to support the Palestinians, while urging them to recognize Moroccan Jews as fellow citizens and to engage them in dialogue rather than through violence. “Many Moroccan Jews continued to voice their allegiance to the country and the king,” writes Boum. “Others, worried about the political situation, heeded the warnings of the Zionist representatives and left.”

In Akka and elsewhere in southern Morocco, he points out, Jews came under intense pressures. “As political animosities in the Middle East intensified, these Jewish communities felt insecure as the distinction between Zionism and Jewishness became blurred.”

Moroccan nationalists, in turn, tried to assure Jews while lambasting Israel. One such politician, Mehdi Ben Barka, wrote in the late 1950s: “We need all our human potential. We want all Moroccan patriots, whether they are Muslims or Jews, to dedicate themselves to the task of national renovation. We expect the Jews to turn their eyes to Israel as we turn ours to Mecca, but if they want to change their nationality, that is bad”

King Mohammed’s successor, his son Hassan, implored Jews to remain in Morocco, promising them continued protection while denouncing xenophobia and racism.

“Despite the king’s guarantee, the political climate, characterized by the influence of Nasserism and the pan-Arab laws of the Arab League about Jewish migration, encouraged feelings against Jews in Morocco, pushing many of them to leave the country,” writes Boum. “At the same time, many political parties failed to oppose this anti-Jewish movement, making it easy for Zionist organizations in Morocco to convince the Jews that their safety lay in Israel.”

Today, Morocco is virtually bereft of Jews. Whereas it was home to 240,000 Jews before 1939, less than 5,000 remain. Few Moroccans, however, are willing to address this sensitive topic. As Boum observes, “A debate in Moroccan society about the status of Jews as citizens is still a national taboo.”

Nonetheless, liberal and independent Moroccan newspapers have published articles about the Jewish community, and more Moroccan Muslims believe they can be critical of Israel without casting aspersions on Jews still living in Morocco.