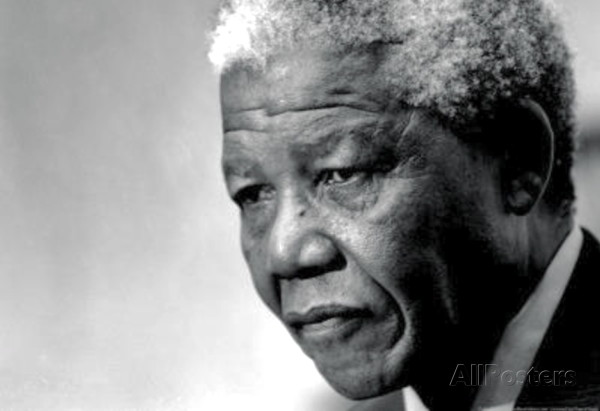

Six years before South African freedom fighter Nelson Mandela was released from imprisonment on Robben Island, launching his career as South Africa’s future first Black president and starting the historic process of phasing in Black majority rule, I visited South Africa in my capacity as a journalist.

It was 1984 and South Africa, a pariah nation which the world had turned against, had just begun to loosen the regulations governing apartheid, a policy introduced by the ruling National party in 1948, the year Israel was born as a sovereign, independent country.

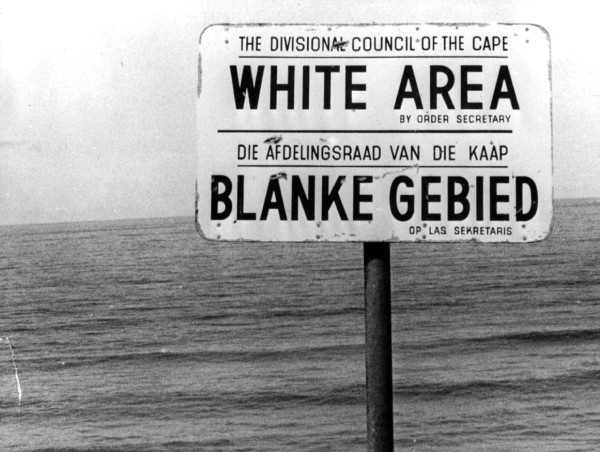

Apartheid, which means apartness in the Afrikaans language, was cynically or sincerely regarded as a form of “democratic pluralism” by the white minority government, which maintained that its racially diverse population — Whites, Blacks, Coloreds and Asians — would be free to be “masters of their own destinies” in their respective areas.

On the face of it, the policy of separate development seemed almost benign. And that’s how South African propagandists portrayed it. But in reality, apartheid was ugly, demeaning and repulsive, a Jim Crow system of racial discrimination and segregation based on white supremacy and resulting in gross injustices and shocking inequalities.

Consisting of a series of draconian laws that broadly determined where a person could live, work, vacation and dine out, or who he or she could marry, apartheid empowered Whites, who could dominate, control and manipulate a rainbow majority of non-caucasians.

Black South Africans like Mandela, their dignity, self-worth and self-respect brutally violated by apartheid, rebelled by taking up arms after non-violent political agitation had failed.

Mandela’s struggle seemed hopeless, especially after he was consigned to purgatory on Robben Island, a few miles off the coast of Cape Town.

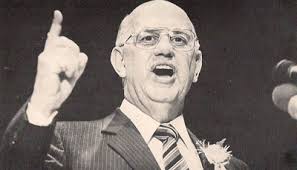

But as the years passed, apartheid came under increasing scrutiny and attack, both inside and outside South Africa. By the early 1980s, international economic sanctions were strangling its economy. In response to the pressure, which had isolated South Africa, the government unveiled the now-forgotten New Dispensation, a set of constitutional edicts designed to give Coloreds and Asians some say in home affairs.

I arrived in South Africa several months before the New Dispensation was promulgated. I was there to gather material for a series of stories on the Jews of South Africa and South Africa’s relationship with Israel.

Jews of mainly Lithuania descent formed the backbone of the community. Their ancestors had fled Lithuania, then a part of the Russian empire, in the late 19th century to escape antisemitism, pogroms and economic hardship.

In general, Jews thrived in South Africa, bouts of Afrikaaner antisemitism notwithstanding. Being white, Jews were members of the pampered privileged class. But how did Jews relate to apartheid? Having been victims of unbridled racism in Europe, Jews could not logically justify or embrace apartheid.

But in actuality, most of the 119,000 Jews who lived in South Africa in the mid-1980s timidly accepted the status quo, while criticizing “petty” manifestations of apartheid like segregated public facilities and separate entrances in buildings for Whites and Blacks.

Jews who could not stomach apartheid emigrated or, like the revolutionaries Joe Slovo, Denis Goldberg or Ronnie Kasrils, joined the illegal resistance movement.

Years later, after he had won the presidency of South Africa, Mandela would gratefully acknowledge the disproportionate role Jews had played in the struggle to dismantle apartheid.

But as I travelled around South Africa in May 1984, I discovered that few Jews really wanted to tamper with the status quo, though many thought that apartheid was a passing episode in South African history and was on its way out. At the time, there was no unanimity whether apartheid would disappear through peaceful evolutionary stages or through upheaval and violence in a bloody civil war.

The community’s official view of apartheid was expressed by the South African Jewish Board of Deputies, its representative body. Aleck Goldberg, then its executive director, told me that it was officially neutral, but that it opposed “unjust discriminatory laws and practices based on race, creed and color.”

Prior to 1948, the Board of Deputies was relatively outspoken in denouncing policies underpinned by racism. But as soon as the Afrikaaner-based National party swept into office, the Board of Deputies backtracked, adopting a policy of non-involvement in politics.

Typically, in one of its play-it-safe resolutions, the Board of Deputies proclaimed, “Jews participate in South Africa’s public life as citizens … and have no collective attitude to political issues … Jews share with their fellow citizens of other faiths and origins a common interest in and responsibility for our country’s affairs and participate in them according to their individual convictions.”

But as opposition to apartheid escalated, the Board of Deputies grew bolder and less cautious. It called for the repeal of the Mixed Marriages Act and of an article in the Immortality Act that forbade inter-racial unions and dating across race lines. It also urged members of the Jewish community “to cooperate in securing the immediate amelioration and ultimate removal of all unjust discriminatory laws and practices based on race, creed and color.”

On a personal level, South African Jews, though wary of rocking the boat, generally voted for the Progressive Federal party, which opposed apartheid and whose leader was the irrepressible Helen Suzman.

I interviewed two of its parliamentary representatives, the MPs Reuben Sive and Harry Schwarz, and they outlined a vision of the future that was totally at odds with official government policy.

Sive, then 70, said he was prepared to accept the heretical notion that South Africa should be governed by a multiracial government in which all racial groups would share power. Sive voted against the New Dispensation, saying it would exclude Blacks from a proposed tricameral parliament, enshrine racial discrimination and leave veto power in the hands of Whites.

Sive’s colleague, Harry Schwarz, was also skeptical of the New Dispensation, saying it had no chance of working unless Blacks were included in the political process.

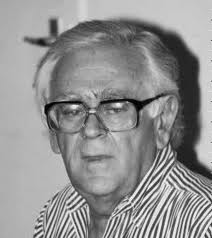

During my trip, I also interviewed Theo Aronson, the first, and only, Jewish Member of Parliament for the National party. A Port Elizabeth lawyer, he supported efforts by Prime Minister P.W. Botha to bring Coloreds and Asians into the parliamentary mainstream. And while he had misgivings about the ban on inter-racial marriage and the prohibition that prevented non-Whites from establishing shops or factories in white central business districts, he justified apartheid.

It was necessary for South Africa’s survival, he claimed.

Universal suffrage, he argued, would not work and would embroil South Africa in the kind of chaos that had engulfed many African countries. When I suggested that his views would be seen as racist outside South Africa, he exclaimed, “I’m a Jew! How can I be a bloody racist?”

As I learned, the majority of Jewish South Africans did not share Aronson’s analysis.

John Moshal, the president of the Council of Natal Jewry, in Durban, told me that apartheid was a dying phenomenon and that it would be replaced by “normal human prejudice,” outside the framework of formal laws enshrining apartheid.

Archie Shandling, a former president of the Cape Town branch of the Board of Deputies, declared, “We, as Jews, have a moral and religious obligation to oppose apartheid, and I would like to see it swept away.”

Jack Penn, a renowned plastic surgeon, said that apartheid was a synonym for institutional discrimination and should be eliminated. “A person must be free to discriminate or not to discriminate, but not by law.”

At the University of Cape Town, a young medical student who preferred to remain anonymous launched a ferocious assault on apartheid: “It stinks and, as far as Judaism goes, it is against everything we’ve learned.”

The chief rabbi of South Africa, Moses Caspar, was more circumspect. He said, “It is necessary, from time to time, to make statements on what I regard as moral issues. Various aspects of apartheid come under this heading.”

Rabbi Scott Saulson, the executive director of the South African Union for Progressive Judaism, said that Jews in South Africa were basically ambivalent about apartheid. As he put it, “They’re in favor of a fair system for Whites and non-Whites, but if political reform goes too far and leads to Black majority rule, Jews may lose their privileges.”

Of course, Saulson was wrong.

Black majority rule is belatedly a fact of life in contemporary South Africa, thanks in no small part to Nelson Mandela and courageous men and women like him, and neither Jews nor non-Jews have become victims of the new order.