Among the distinguished historians of the Holocaust, Michael Marrus was the sole Canadian in that exalted group.

A University of Toronto professor for close to 50 years, he was the author of eight books, at least two of which are standards in the field, and a panoply of monographs.

It would be fair to say that Marrus’ exacting scholarship was on a par with that of internationally renowned scholars such as Raul Hilberg, Philip Friedman, Christopher Browning and Yehuda Bauer.

Considering that he never aspired to be an expert in this discipline, his achievements were all the more astonishing.

Marrus died on December 23 in Toronto, his birthplace, leaving behind a durable legacy. He was 81.

I knew Marrus in the 1980s and 1990s, when he was the first person to hold the Chancellor Rose and Ray Wolfe Chair of Holocaust Studies at the University of Toronto and when he was a member of the International Catholic-Jewish Historical Commission, which had been established by the Vatican to study the role of Pope Pius XII during World War II.

Over the course of two decades, I interviewed him twice in person and several times on the telephone. A serious, no-nonsense individual who answered questions directly, he was totally committed to his craft.

Like his father, Elliott, Marrus aspired to be a lawyer, but after enrolling at the University of Toronto and working in his father’s law office during summer breaks, he decided his true vocation was history. After obtaining a BA degree with a major in that subject, he earned an MA and a PhD in European history at the University of California, Berkeley.

Specializing in the topic of social change in 19th century France, he wrote his doctoral dissertation on the assimilation of French Jews during the sensational Dreyfus affair.

France was ideologically torn asunder after Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army, was falsely accused of treason and stripped of his position. Dreyfus’ dismissal, trial, conviction, imprisonment and exoneration convulsed France from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries. His persecution underscored the prevalence and perniciousness of antisemitism in the first European nation to emancipate its Jewish citizens.

Thinking that his postgraduate thesis had the potential to attract a readership, he converted it into The Politics of Assimilation, which Oxford University published in 1971, when he was 30 years old.

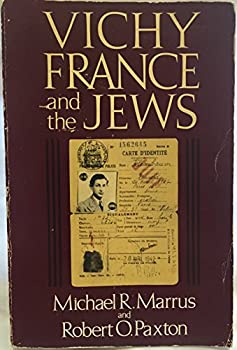

Impressed by its erudition and fluency, Robert Paxton — an American scholar who had written Vichy France — asked Marrus whether he would collaborate with him on a book about Jews under the Vichy regime. Established following Germany’s occupation of France in 1940, Vichy persecuted French and foreign Jews and cooperated with Germany in the deportation of some 75,000 Jews to Nazi extermination camps.

Marrus gladly accepted Paxton’s invitation. “Paxton was one of the leading historians on Europe,” Marrus told The Globe and Mail. “I was flattered to be asked.”

The pair delved into French archives, studying a vast array of monographs, memoirs and secondary works. Their objective was to challenge the specious Vichy claim that German pressure was at the root of Vichy’s marginalization, demonization and persecution of Jews in France.

Having pored over a mountain of material regarding Vichy’s relations with Nazi Germany and Vichy’s antisemitic edicts, Marrus and Paxton produced a path-breaking, best-selling classic, Vichy France and the Jews, which was published in 1981.

They proved beyond a reasonable doubt that Vichy’s antisemitic policies were initiated and implemented not by the German occupiers but by French antisemites like Xavier Vallat and Darquier de Pellepoix, the successive commissioner-generals for Jewish Affairs, who had been greatly influenced by the reactionary Charles Maurras.

They also demonstrated that the Statut des juifs, Vichy’s antisemitic legislation, went beyond Germany’s anti-Jewish regulations.

A reviewer in The New York Times, calling attention to their “exhaustive research and the sobriety of their prose,” concluded that their indictment of Vichy France was “far more powerful than previous works on the subject.”

The extraordinary success of Vichy France and the Jews emboldened Marrus to focus almost exclusively on the Holocaust for the rest of his flourishing career. The sole exception was Mr. Sam, a biography of Samuel Bronfman, the Montreal-based tycoon and Jewish community leader.

In 1987, Lester & Orpen Dennys published one of his most important books, The Holocaust in History, which was advertised as the first comprehensive assessment of the vast historical literature on the Shoah and an attempt to “integrate Holocaust history into the general stream of historical consciousness.”

Marrus, in dispassionate fashion, examined pertinent issues that consumed specialists like himself: How did Adolf Hitler’s antisemitic policies evolve into mass murder? How should the roles of Nazi collaborationist governments and the Allies be evaluated? What are the lessons of the Holocaust?

Apart from The Holocaust in History, Marrus wrote, among other works, Some Measure of Justice, an examination of restitution programs for survivors, and Lessons of the Holocaust, which was praised by the eminent Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan. As well, he edited Historic Articles on the Destruction of European Jews, a 15-volume set translated into German.

Marrus was not only an academic, but an administer. He was dean of the School of Graduate Studies for seven years. And he served on the university’s governing council for nearly two decades.

In 1999, in a substantive departure from his usual activities, he accepted an appointment on the Vatican’s International Catholic-Jewish Historical Commission, which was charged with evaluating eleven volumes of archival documents it had released on the papacy of Pius XII during the war.

On behalf of the six commissioners, half of whom were Jewish, Marrus drafted 47 questions that not only required straightforward answers but a lot more Vatican documents.

Initially, Marrus was confident that it would cooperate. But when he realized he had hit a “brick wall,” he was deeply disappointed and disillusioned. Having been rebuffed, Marrus resigned in 2001, the year the commission itself was disbanded.

Twenty one years later, the Vatican opened the archives to scholars, and last June, Pope Francis ordered the online publication of files relating to Pope Pius XII’s interactions with Jews during the Holocaust.

According to The Pope at War, a book by David Kertzer published recently, the Vatican was most concerned about helping or saving Jews who had converted to Catholicism and the half-Jewish children of Jews who had married Christians.

Marrus was known to be a cautious man who chose his words carefully, but in 2017 he committed a horrendous faux pas that would haunt him for the remainder of his life.

During a session at Massey College, a graduate residential building on campus, Marrus was seated at a table with Hugh Segal, the then master of the institution, and three junior fellows. Turning to a black woman, Marrus pointed at Segal and said, “You know this is your master, eh? Do you feel the lash?”

Rising from her chair, the woman retorted, “If this man (Marrus) doesn’t know what he has done wrong, you better explain it to him.”

Marrus’ inappropriate and offensive remarks were branded as a racial slur, forcing Marrus to resign in disgrace. The resignation devastated him, said his close friend, the historian Harold Troper.

Several years later, Marrus acknowledged he had erred. “It was silly,” he said. “I never meant to hurt her.”

The Globe and Mail, in an editorial, came to his defence, commenting that he had been treated unfairly. But the damage was done and Marrus had to carry this heavy burden for the rest of his days.

This blemish notwithstanding, Marrus’ record as a teacher and a historian has steadfastly stood the test of time. He was one of the stellar historians of our time, and his books and monographs are his shining monuments.