Michael Igor Peschkowsky, a young Jewish immigrant from Nazi Germany, transformed himself into Mike Nichols in the United States. He became a struggling actor, an acclaimed standup comedian and a celebrated movie, theater and television director. Mark Harris, in his thorough biography, Mike Nichols: A life (Penguin Press), traces the trajectory of his luminous career.

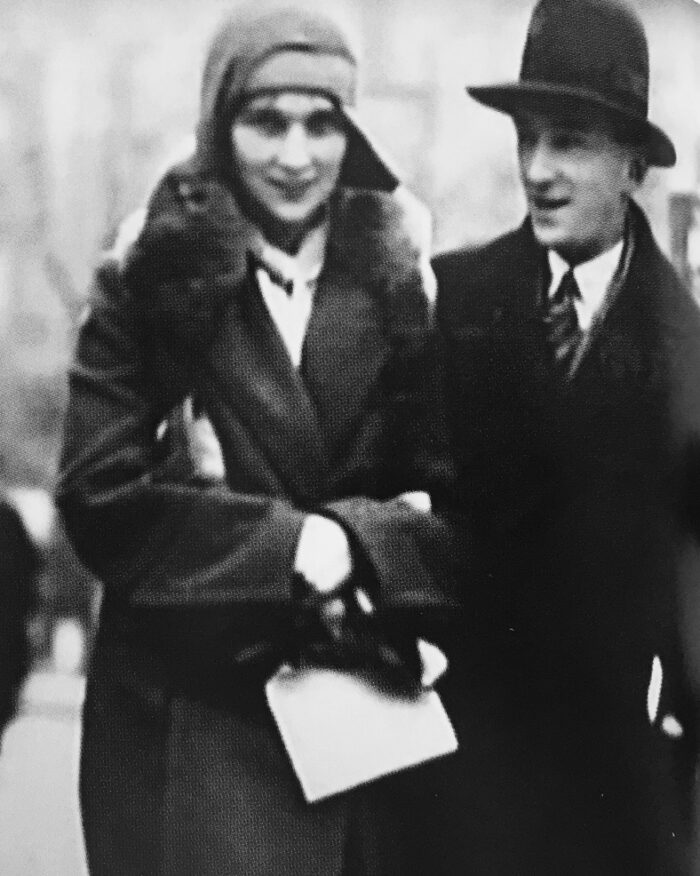

Born in Berlin in 1931, he was the son of a most unusual couple. His father, Pavel, a physician of Russian origin, was an anti-Bolshevik supporter of Alexander Kerensky. His mother, Brigitte, a social worker, was a German Jew whose cousin was Albert Einstein. Her father, Gustav Landauer, a socialist who held a ministerial post in the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic in 1919, was murdered by the paramilitary Freikorps.

Pavel and Brigitte were married in 1930 during the final years of the Weimar Republic. By 1938, they finally realized they were in grave danger. Pavel, who later changed his name to Paul, went to New York City, where he found work as an X-ray technician.

Nichols and his brother departed Germany in 1939, two weeks before the ill-fated voyage of the St. Louis, a passenger ship filled with German Jewish refugees who would be denied entry to Cuba, the United States and Canada. Brigitte emigrated in 1940, just months before the Nazi regime forbade Jews to leave.

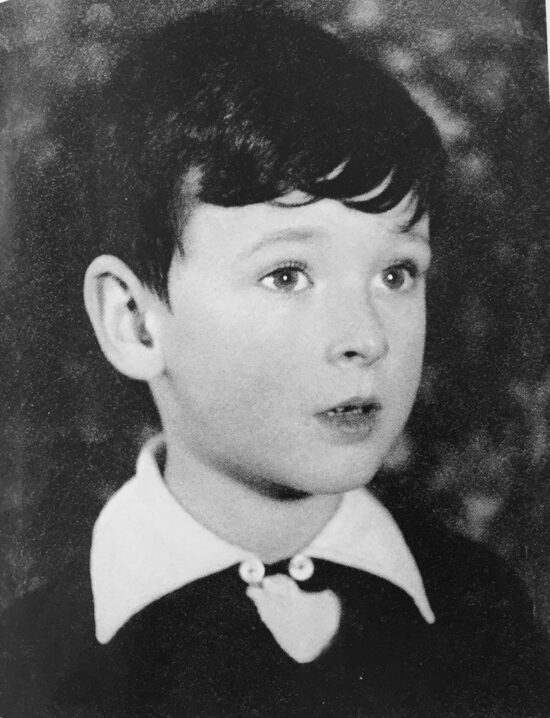

Having passed the state medical exam, Pavel set up a practice whose patients included the pianist Vladimir Horowitz and the impresario Sol Hurok. Nichols picked up English quickly, but spoke with an accent and felt like an outsider. At school, he was bullied and encountered antisemitism from one of his teachers.

Pavel died in 1944, having contracted leukemia due to his exposure to radiation from the X-ray equipment he operated. He was 44. Brigitte struggled to make ends meet and suffered from many ailments. During this unstable period, he and his family lived in poverty. He coped with shyness and isolation, worked at dead-end jobs, discovered movies, and lost the last vestiges of his German accent.

At the University of Chicago, he had so little spending money that he would linger in the cafeteria after students had left so that he could eat the leftovers off their plates. For a while, he contemplated studying psychiatry, but was more interested in winning roles in plays mounted by the campus theater. In his second year, he dropped out of university.

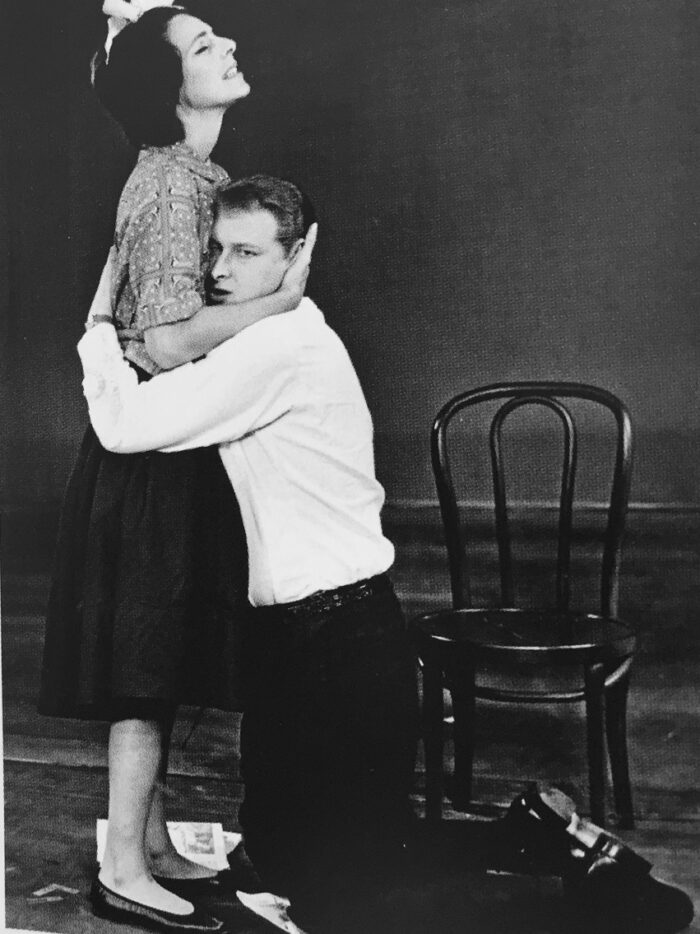

While still a student, he met Elaine May, whose father, Jack Berlin, had been an actor and director in the Yiddish theater. He and May would team up to perform improvisational sketch comedy rooted in “deep observation of the tics, vulnerabilities, insecurities, vanities, and pretensions of others, and of themselves,” says Harris.

They made their national television debut on The Steve Allen Show in 1957. Shortly afterwards, they appeared on NBC’s popular program, Omnibus. Time magazine pronounced their satire as “fresh, inspired stuff.” They never looked back, earning a ton of money. They parted ways some years later, but over the next five decades they would perform together, and Nichols would never direct a film without showing her the script.

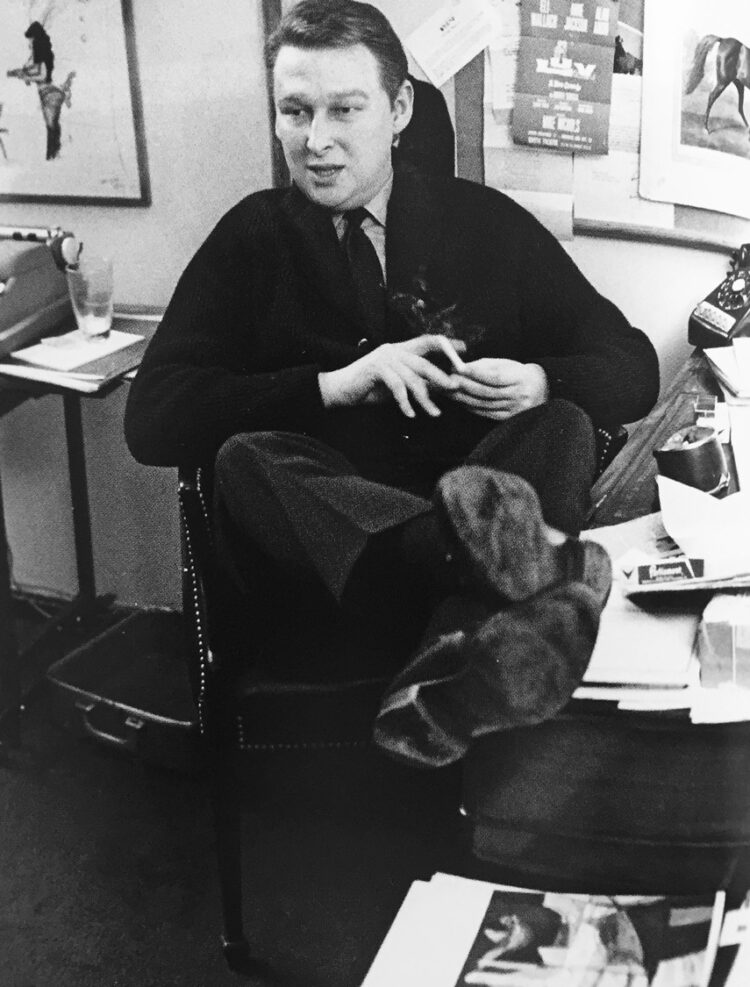

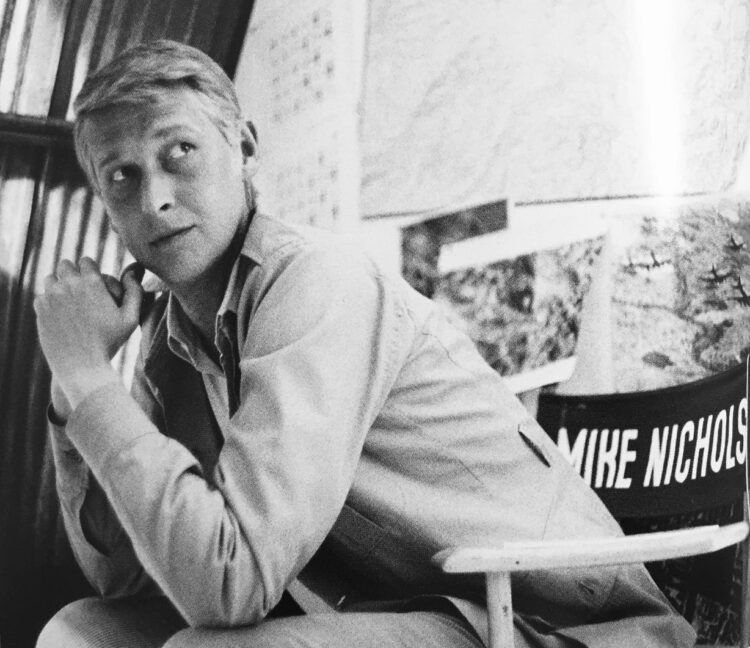

Before he and May achieved stardom, Nichols was what Harris describes as “a comic character actor” and the host of a radio show in Philadelphia. In 1963, he directed his first Broadway play, Barefoot in the Park, which earned plaudits from critics. Around this time, he directed his first movie, The Knack, a sex comedy.

Nichols broke into the big time when he was hired to direct Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. The film was a smash hit, winning 13 Academy Award nominations. Nichols’ success in Hollywood was ironic, given his condescending view of it as “an oasis of tacky luxury and seductive schlock,” Harris writes.

He went on to direct The Graduate, which became the third-highest grossing film in history after Gone With the Wind and The Sound of Music. After directing Catch-22 and Carnal Knowledge, Nichols made The Day of the Dolphin, the “first sloppy decision of his career,” in Harris’ estimation. Another one of his miscalculations was directing Gary Shandling’s sex comedy, What Planet Are You From? He earned a record $8 million from it, but it was a box office bust.

To his probable regret, he passed on Sophie’s Choice, starring Meryl Streep and based on William Styron’s novel about a Polish Holocaust survivor. Harris speculates that Nichols, never having given much thought to his parents’ exposure to antisemitism in Nazi Germany, could not bring himself to direct a movie about the Holocaust.

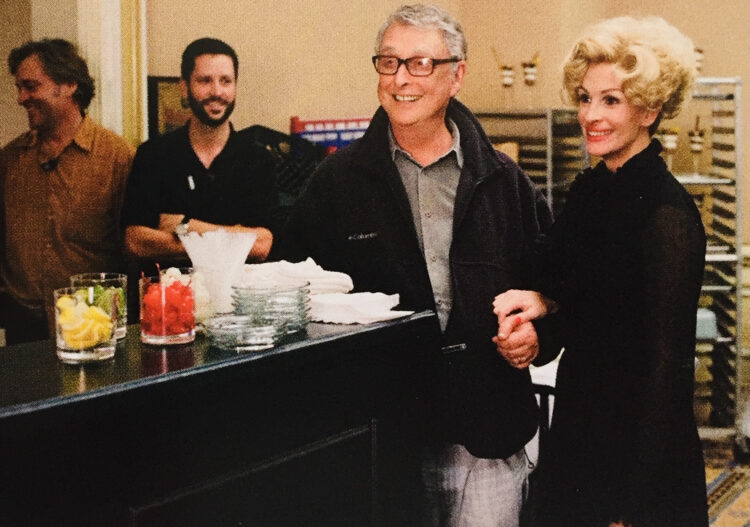

He would direct Streep in one of his next films, Silkwood, and the pair bonded. In Streep, he found a kindred soul whose work ethic he admired.

By the early 1980s, as Harris observes, Nichols was a rich man who “enjoyed living like an even richer man.” But his health was in decline. He was overweight, smoking too much, working long hours and using cocaine.

Nichols’ fourth and final marriage was his happiest. His new wife, Diane Sawyer, was a television correspondent and the first woman to co-anchor the 60 Minutes show.

The project he was most proud of, the miniseries Angels in America, was broadcast on HBO in 2003. The filmmaker Elia Kazan called it “the most powerful screen adaptation of a major American play since A Streetcar Named Desire.”

Charlie Wilson’s War was the last film he directed. His production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, which opened in 2012 to mostly rave reviews, earned Nichols his seventh Tony award.

As his schedule got cluttered with doctors’ appointments, Nichols began seeing a psychiatrist about his fear of dying. By then, he was coping with a heart ailment and weakening vision.

The last week of his life was a busy one, says Harris. A day after his pacemaker was adjusted, he complained of feeling dizzy and collapsed. He died in 2014, surrounded by his family.

Broadway theatres dimmed their lights in his honor.

It had been a good run.