Bolshevik troops seized the Belorussian city of Minsk — a historic Jewish center — in July 1920, ending successive Polish and German occupations and liberating its Jewish population from czarist oppression. By the same token, the new Soviet order banned Jewish political and cultural organizations outside the Communist party, including Zionist groups, and began closing synagogues and Jewish institutions.

Jews outwardly adapted to these seminal changes, welcoming their emancipation from state antisemitism and filling positions in the communist hierarchy. But in the face of this transformation, a great many Jews worked to preserve their ethnic identity, writes Elissa Bemporad in her excellent, deeply-researched book, Becoming Soviet Jews: The Bolshevik Experiment in Minsk, published by Indiana University Press.

“While adapting to the new system, many Jews, whether former Bundists, Yiddish activists, political Zionists, religious practising Jews, or Russified liberals remained committed to some expressions of Jewishness,” says Bemporad, a professor of East European Jewish History and the Holocaust at Queens College, City University of New York. “They attempted to walk the fine line between accepted Soviet behavior and social norms and expressions of Jewish particularity.”

Bemporad’s study of the Jewish acculturation process into the Soviet system basically takes a reader from the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution to World War II, a period during which the encounter between pre-revolutionary Jewish life and the Soviet Union was traumatic at times.

She analyzes this turbulent era against the backdrop of Minsk’s place in Jewish historical memory. Situated in the heart of the Pale of Settlement, the area where most Russian Jews lived until about 1945, Minsk was inhabited by a mix of Belorussians, Russians, Poles, Jews and Tatars.

Settled by Jewish traders in the 16th century, Minsk was home to between 48,000 and 71,000 Jews during the interwar years, when more than three million Jews lived in the Soviet Union. At various times, Jews represented one-third to 43 percent of Minsk’s total population, with the majority eking out a living as craftsmen, small traders and skilled workers.

During the czarist epoch, Jews were largely excluded from positions of prominence and were generally forced to reside in the Pale of Settlement. With the end of the Romanov monarchy, they attained political and civil rights and joined the Soviet bureaucracy and leadership in a variety of roles.

In general, the Jews of Minsk supported the Soviet takeover because pogroms had accompanied the previous Polish occupation. But Jews paid a heavy price for the sovietization of Minsk, which was carried out by the Evsektsiia, the Jewish section of the Communist Party. The Bolsheviks, she notes, dismantled Jewish institutions from kosher meat slaughtering plants to yeshivas. Jewish Communist officials who attended synagogue, or whose sons had been circumcised, were expelled from the party.

Zionist organizations, with the temporary exception of left-wing groups like Poale Zion, were outlawed. In the mid-1920s, Zionist youth leaders were arrested, and Hebrew-language publishing houses were gradually closed. Meanwhile, the Bund was forced to merge with the Communist Party.

As Bemporad observes, the revolution had a marked impact on the socio-economic position of Jews. By 1926, seven percent of Jews were engaged in commerce, compared to 85 percent two or three decades earlier. The proportion of Jewish craftsmen dropped significantly. Jews moved into the public sector, playing a key role in managing the economy of the Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.

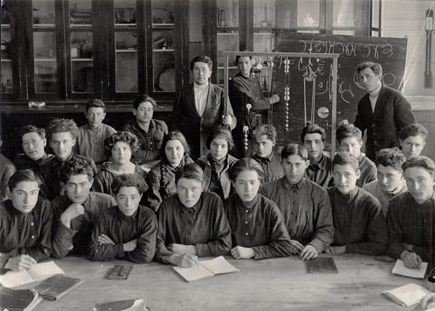

The Soviets recognized Yiddish as the language of the Jewish minority, endorsed it as the true essence of the Jewish proletariat’s national identity and chose it as the official language of instruction in all Jewish secular schools. These schools provided employment opportunities for Yiddish-speaking Jews from all corners of the Soviet Union, she adds.

Yiddish was displayed in public spaces in Minsk, which had the highest proportion of Yiddish speakers in the Soviet Union. As Bemporad points out: “On the building of the Central Train Station of Minsk, the name of the city appeared not only in Belorussian, Russian and Polish, but in Yiddish as well.”

Joseph Stalin’s terror campaign, aimed at “bourgeois nationalists,” claimed the lives of upwards of two million citizens. Inevitably, it affected Jews across the board. Yiddish-language institutions disappeared. “Bundism” became synonymous with “anti-Soviet counter-revolutionary activity.” Zionism was denigrated as a form of bourgeois nationalism.

During the 1920s and the first half of the 1930s, before Jewish culture was virtually squeezed out of existence, the overwhelmingly Jewish neighborhoods of Minsk had a salutary impact on Jewish life. As Bemporad puts it, “The proximity of these Jewish urban spaces, coupled with Jewish residential segregation, promoted ethnic self-identification among Jews, countering the speed of assimilation that was more rapid in ‘non-Jewish’ neighborhoods.”

Awareness of Jewish identity was also fostered, if only inadvertently, by Yiddish-language schools, occupational patterns among the Jewish working-class and cultural events such as a Sholem Aleichem exhibition at the Belorussian State Library.

These and other manifestations of Jewish consciousness came under attack in 1937 with an orchestrated campaign of criticism in the media. Moshe Kulbak, an eminent Yiddish writer, was arrested. Yiddish signage was removed from the train station. Yiddish-language schools were liquidated on the grounds of underenrollment and Jews were pressured to use Russian instead. In addition, Jews were urged to intermarry with Belorussians.

Despite the crackdown, the Belorussian State Jewish Theater and 10 synagogues in Minsk continued to function, at least until Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. More importantly, the Soviet Union staunchly opposed antisemitism, which flourished in neighboring nations.

“In the context of the anti-Jewish policies adopted by Poland and Germany, the USSR appeared as the only country in Europe that still deemed antisemitism a crime,” she writes. “The condition of Soviet Jewish culture and life deteriorated in the late 1930s, but many Soviet Jews in the depth of their heart felt assured by the fact that they lived in a country that officially struggled against antisemitism, in the midst of fascist Europe.”

Soviet Jews were shaken by Moscow’s non-aggression pact with Berlin in August 1939, but Stalin’s short-lived alliance with Adolf Hitler did not impinge on the status of Jews in the Soviet Union.

From 1941 until 1943, the Jews of Minsk were ghettoized and murdered by the Nazis, while Jewish institutions were wiped out. After the Holocaust, 2,500 Jews who had fled Minsk returned, joined by a few thousand families from surroundings towns and villages Most survivors eventually left Minsk, bound for cities elsewhere in the Soviet Union.

A request by the Jewish leadership to reopen Jewish schools and institutions in Minsk was rebuffed by local authorities. In 1951, the Jewish cemetery was closed down, and in the mid 1970s, an older Jewish cemetery was bulldozed to make way for a soccer field. Shockingly enough, postwar guidebooks of Minsk ignored its gloried Jewish past.

And in stark contrast to the pre-war period, Bemporad goes on to say, “antisemitism was encouraged” by the powers-that-be. Sadly, as she says, antisemitism became “the single most important “factor in sustaining Jewish identity” in Minsk.

In closing, she explains that she wrote Becoming Soviet Jews to memorialize the prewar Jewish community of Minsk, which was “first brutally erased from history and then knowingly removed from public memory.”

It’s a poignant way to end an exemplary work of scholarship.