The Middle East as we know it today was forged in the crucible of World War. This incredibly destructive war drastically redrew the regional map, sweeping away the sprawling Ottoman Empire and creating a host of new nations ranging from Turkey and Syria to Iraq and Lebanon. It also gave rise to Arab nationalism and invigorated the Zionist movement.

These historic developments are explored extensively and with expertise in two thoughtful books — The Great War & the Middle East (Oxford University Press) by Rob Johnson, and The Ottoman Endgame: War, Revolution, and the Making of the Modern Middle East, 1908-1923 (Penguin Books) by Sean McMeekin.

As McMeekin points out, it was Russian czar Nicholas I who, in 1853, first broached the idea of partitioning the Ottoman Empire, which he contemptuously labelled as the “Sick Man” of Europe. Although this Islamic empire was difficult to defend and harder still to conquer, Russia, in the name of Christian Orthodoxy and pan-slavism, invaded it five times in the 19th century, seizing three provinces in the Caucasus.

Yet Russia was not the only major power lusting for a slice of the Ottoman territorial pie, as Johnson says. France seized Tunisia, Britain occupied Egypt, the Austro-Hungarian Empire annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina and Italy grabbed Libya. Prior to these events, the Christians in the Balkan provinces rebelled, broke away and declared independence.

But even as the imperial scramble for the Islamic Ottoman Empire heated up, the sultan, Abdul Hamid II, became the object of scorn of ambitious Turkish army officers and politicians, who blamed him for eviscerating the constitution of 1876 and sidelining parliament. In the first decade of the 20th century, opposition to his rule coalesced around the secular Committee of Union and Progress, colloquially known as the Young Turks.

Ironically, all this occurred during a period of rapid modernization that enhanced the empire’s strategic position. “Railways, telegraphs and paved all-weather roads were beginning to unite the empire, improving communications with provincial authorities while giving a solid spur to internal trade,” writes McMeekin. In addition, new professional colleges, state schools and libraries were established to serve an increasingly literate urban population.

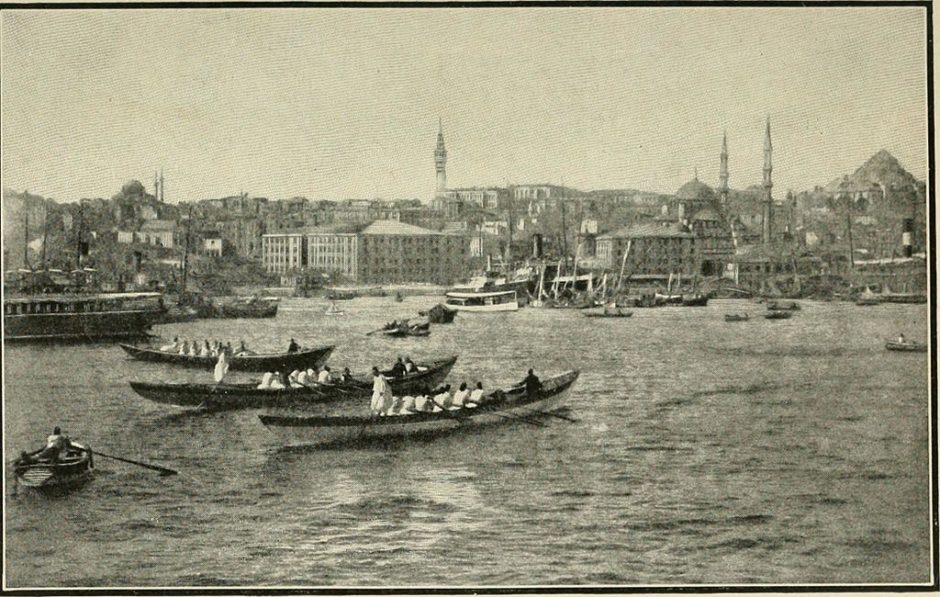

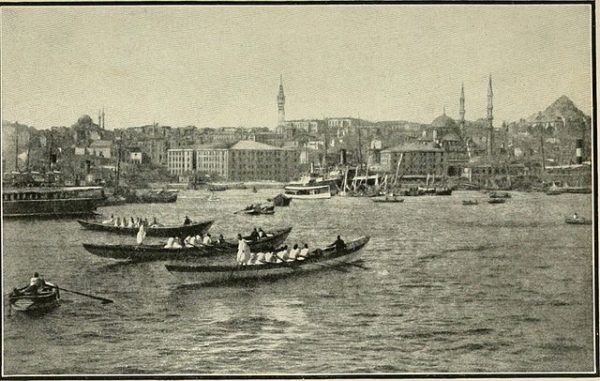

On the eve of World War I, Britain, France, Russia and Germany, all rivals, worked feverishly to secure their influence in the region. But it was Britain and Germany that played the leading roles in determining the future of the empire, headquartered in Constantinople. British policy was to preserve it so as to thwart Russian and German imperialist designs. But Britain’s condemnation of brutal repression within Ottoman domains only served to justify foreign intervention in its affairs, notes Johnson.

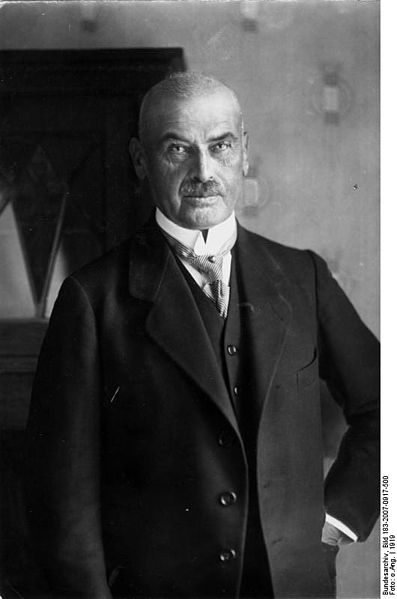

A shared fear of Russian power brought together Germany and the Ottomans. Their convergence of interests reached new heights in 1913 with the appointment of German general Liman von Sanders to reorganize the creaking Ottoman army. Within a year of that date, the Germans and the Ottomans formed a military alliance. But as McMeekin observes, the empire was “woefully unprepared” for a war on such a massive scale, German assistance notwithstanding.

As the war in the Middle East raged, pitting mighty empires against each other in dreadful clash of steel and blood, Britain and France secretly conspired to divide up Ottoman spoils.

By the terms of the 1915 McMahon-Hussein correspondence, the Arabs were awarded large swaths of territory in exchange for supporting the Allied war effort. And according to the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement, revealed by the new Bolshevik regime in Russia, Britain was to acquire Palestine, Jordan and Iraq, while France was to receive Syria, southern Turkey and a portion of northern Iraq. Russia would get Constantinople (Istanbul) and Armenia. A year later, much to the disgust of the Arabs, Britain issued the Balfour Declaration promising Zionists a national homeland in Palestine.

Johnson, charting the progress of the war in minute detail, claims that Britain’s capture of Jerusalem in 1917 marked a major turning point in the war. “The fall of Jerusalem represented the last of the most significant religious sites taken by the British and their allies. From this point on, the Ottoman Empire could only fight a rearguard action.”

McMeekin says that T.E. Lawrence’s involvement in the political machinations that rocked the Middle East was largely accidental. Attached to a mission led by Ronald Storrs, the Oriental secretary in Cairo, Lawrence was thrown into contact with Abdullah, a key Hashemite figure and Arab nationalist who eventually turned the tables on the Ottomans.

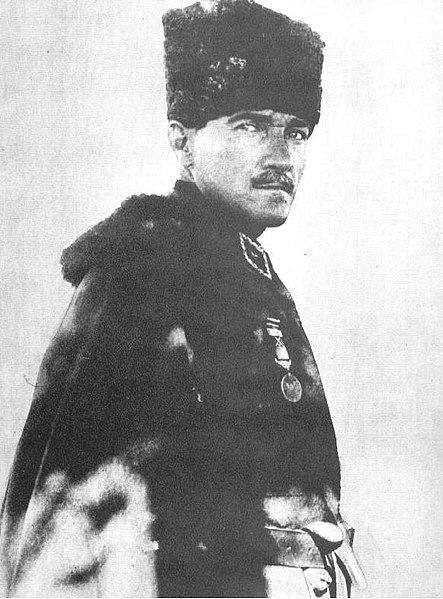

The emerging Turkish state in Anatolia, the heart of the Ottoman Empire, would have been snuffed out out existence by Allied armies had it not been for the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. A Turkish nationalist, he pushed back the aggressors, abolished the empire in 1922, established the republic and drove out 1.2 million Christians in 1923, and consigned the caliphate to the dustbin of history in 1924.

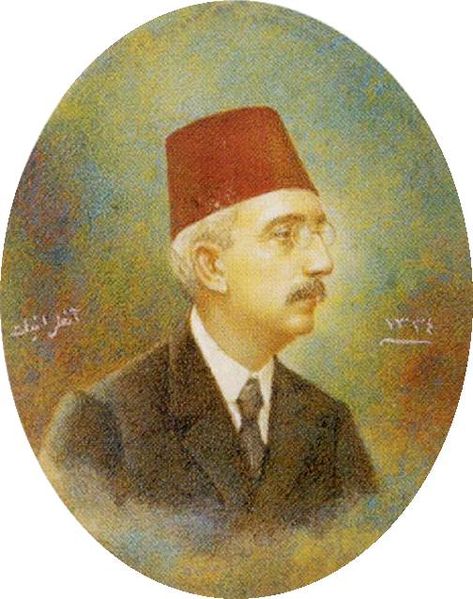

The Ottoman sultan who had authorized the empire’s entry into the war, Mehmet V, did not live to witness the end of it. He died in June 1918, four months before the armistice silenced the guns. His successor, Mehmet VI, the last Ottoman sultan, ruled for only four years.

By Johnson’s reckoning, Britain and France emerged triumphantly from the war in the Middle East, acquiring colonies in Palestine, Syria, Lebanon and Iraq, while the ambitions of Russia and Germany were thwarted.

As Johnson and McMeekin would most likely would agree, the Middle East was never the same again after these tumultuous events.