In 2009, Javier Sinay, a journalist in Buenos Aires, received an email from his father alerting him to a 1947 newspaper article written by his great-grandfather, Mijl Hacohen Sinay, concerning the murders of 22 European Jewish settlers in Moises Ville from 1889 to 2006.

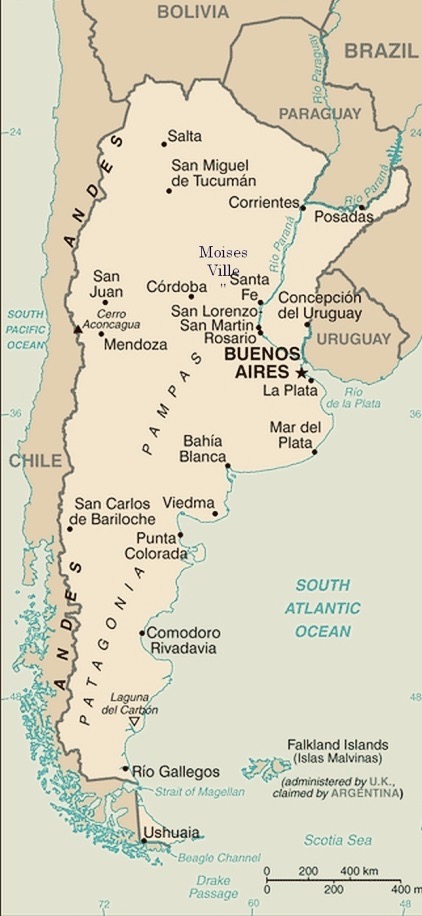

The email piqued his interest in Moises Ville, one of the first agricultural colonies in Argentina settled by Jews fleeing pogroms in czarist Russia.

His book, The Murders of Moises Ville: The Rise and Fall of the Jerusalem of South America (Restless Books), delves into this unique facet of Argentina’s history. Though long-winded and disjointed at times, it provides readers with a panoramic picture of an intriguing experiment in social engineering.

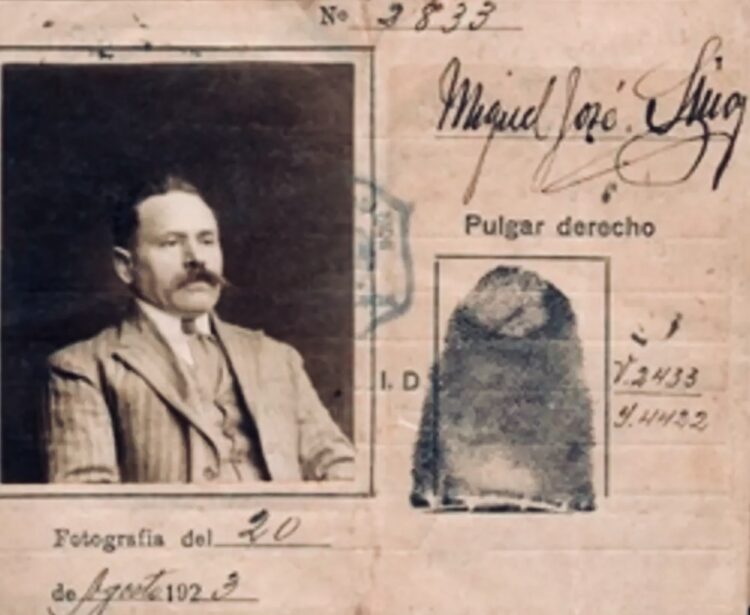

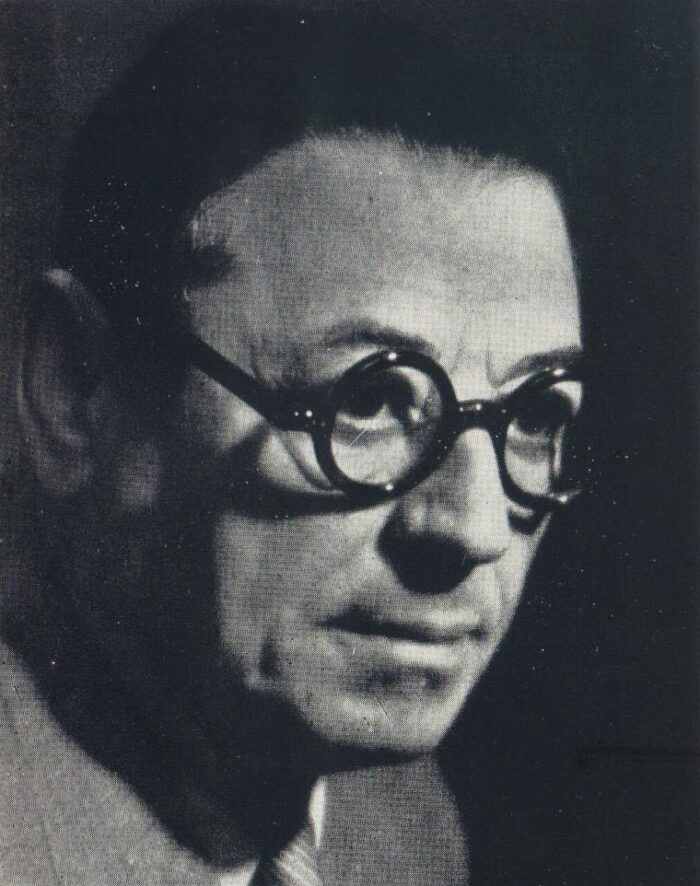

Sinay’s great-grandfather, born in 1877, immigrated to Argentina in 1894 and settled in Moises Ville, in Santa Fe province. Employed as a teacher at its first school, he moved to Buenos Aires in 1898 and founded the first Yiddish newspaper in the country, Der Viderkol.

He died in 1899 without ever having told his son about his sojourn in Moises Ville, one of five colonies established in Argentina’s 22 provinces by Jews from Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Poland and Lithuania. These settlers endured hardships ranging from hunger to illness. During the 1920s, nearly 50 percent of Argentinian Jews lived in these settlements.

Five hundred kilometres northwest of Buenos Aires, Moises Ville was the creation of the Jewish Colonization Association, which was founded by the businessman/philanthropist Maurice de Hirsch.

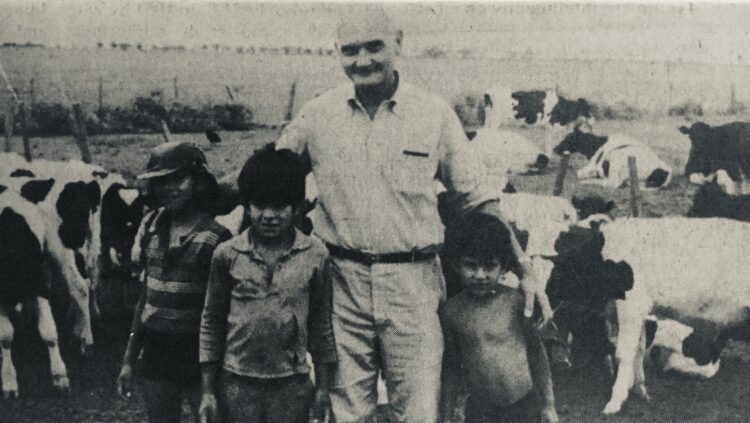

In the spring of 1982, about a month before Argentina and Britain clashed in the Falklands War, I visited Moises Ville. I flew there from Buenos Aires to Rosario, and then I was driven to the colony, which looked like a cross between an Israeli moshav and a Canadian prairie town.

I met several of its residents, one of whom was a dairy farmer named Aaron Jeifetz, who owned a 1,300 hectares ranch on the pampas, the treeless, grassy plain that covers so much of Argentina.

As Sinay writes, the first Jewish colonists to arrive in Argentina were from Kamenetz-Podolsk, in the region of Podolia. Their steamship, the Weser, dropped anchor in Buenos Aires on August 14, 1889.

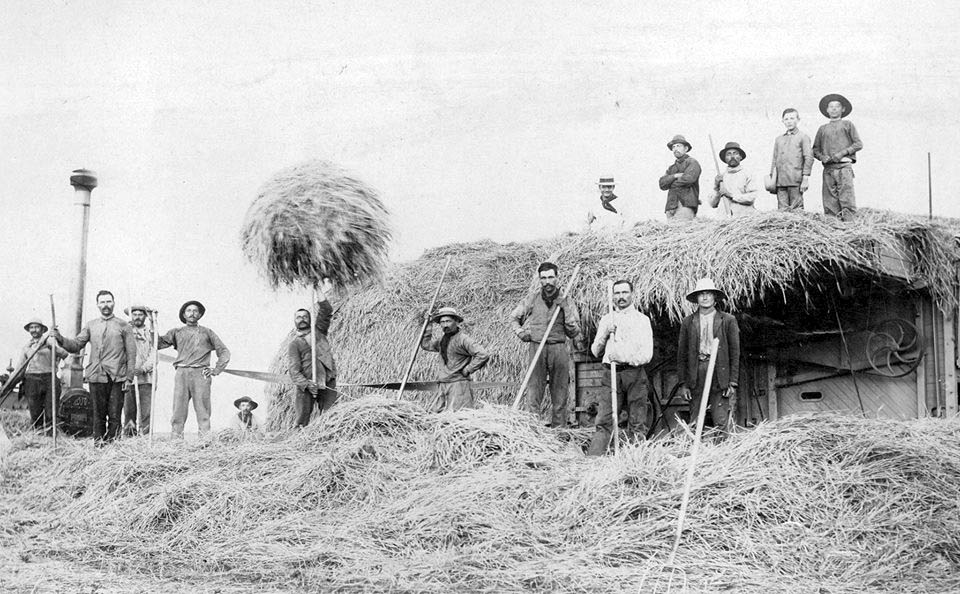

Apart from wheat, the colonists planted alfalfa, corn and flax, battling droughts, floods, locusts and weeds. They opened dairy farms and creameries. And they built factories to produce toys, soap, soda and candy.

During the late 1930s, Moises Ville welcomed dozens of displaced Jews who had been driven out of Nazi Germany.

At its peak, from the 1920s to the 1950s, Moises Ville had a population of 6,000, perhaps 1,000 more than today. There were five schools, four synagogues, a movie theater, and two libraries which held more than 20,000 books.

Today, Moises Ville is inhabited by 117 Jewish families, with 90 percent of its population being Christians. The reason is clear. Young Jewish people left by the hundreds, going to big cities in search of an education and employment opportunities. Two-thirds of its residents had departed by the end of the 19th century.

The exodus is described jocularly by one of the descendants of the pioneers: “We planted wheat and harvested doctors.”

By one estimate, 500 to 600 Moise Ville families live in Israel today. Proportionately, no other town in the world has sent as many immigrants to Israel. Two Israeli ambassadors were born and raised in Moises Ville.

During its heyday, the Jewish gaucho, or cowboy, loomed large in Moises Ville’s lore. He was a figure glamorized by the Jewish novelist Alberto Gerchunoff.

“The Jewish gaucho became fashionable,” says Sinay. “But did Jewish gauchos exist in Moises Ville? Maybe. I, as of now, have never seen one.”

To Sinay, Moises Ville increasingly resembles an “open-air museum.” Since 1999, it has been a National Historical Town due to its singular Eastern European features.

Moises Ville, too, was a trailblazer.

Its cemetery was the first Jewish one in Argentina. Its rabbi, Aharon Halevi Goldman, was the first Russian rabbi to arrive on the pampas. Its agricultural cooperative, La Mutua Agricola, was the first of its kind in Santa Fe province. Its schools were the first ones in the entire region.

In every respect, Moises Ville led the way.