Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park, straddling the border of northeast Arizona and southeast Utah, conjures up an aura of deja vu in the best sense of the word.

As soon as I arrived here on my first visit, I felt an immediate and personal connection. The iconic red sandstone mesas, buttes, pinnacles and spires held me in awe and admiration, yet I had seen them before. As a movie fan, I had been transported to Monument Valley on numerous occasions, revelling in its austere beauty.

Since the 1930s, dozens of feature films, particularly Westerns, have been shot on location in this 30,000-acre reserve, which novelist Zane Grey described as “a strange world of colossal shafts and buttes of rock magnificently sculptored, standing isolated and aloof, dark, weird, lonely.”

Monument Valley forms a chunk of the 27,000 square mile semi-autonomous Indian-governed Navajo Nation in Arizona, Utah and New Mexico. Established in 1868, enlarged in a series of land transfers to the Navajos by the federal government and then ceded to them by President Chester Arthur, it’s the largest single expanse of territory held by an Indian tribe in the United States.

For decades afterwards, the reserve lay off the beaten track, one of the remotest areas in the country, a place where the Navajo herded cattle and sheep and made wool, yarn, blankets and carpets.

In 1938, a local cattle rancher named Harry Goulding learned that United Artists, a Hollywood film studio, intended to shoot a Western in the southwest. The first American Western movie, The Great Train Robbery, had been shot in the flatlands of New Jersey and Delaware in 1903. But now, an up-and-coming director, John Ford, sought a far more dramatic and authentic backdrop for the Western he planned to make.

Goulding had opened a trading post near Monument Valley in 1923, but the Depression, plus the droughts of 1934 and 1936, virtually bankrupted him. Convinced he could reap benefits from a film shoot in Monument Valley, he commissioned photographer Joseph Muench to compile an album of photographs of its stunning vistas.

With Muench’s album in hand, Goulding and his wife drove to Los Angeles to convince the studio to consider Monument Valley as a venue for its next Western. Though he didn’t have an appointment, he managed to wrangle a meeting with the location manager, who was duly impressed by Muench’s set of photographs.

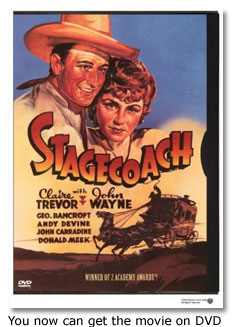

Ford shot part of Stagecoach in Monument Valley, immortalizing some of the most enduring images of the American West. Starring Claire Trevor, Thomas Mitchell and John Carradine, it launched the career of one of the unknown actors who had landed a minor role in it, John Wayne. Stagecoach won an Academy Award nominee for best picture in 1939, a bumper year for first-rate movies.

Ford returned to Monument Valley to make, among other Westerns, My Darling Clementine (1946), She Wore A Yellow Ribbon (1949) and Rio Grande (1950). He also filmed The Searchers (1956) — one of the classics of the Western genre — there.

Stagecoach has had an enormous impact on the local economy. Goulding built a lodge to accommodate the crew. Later, he expanded it to accommodate the flood of tourists streaming into Monument Valley.

Ford, having hired hundreds of Navajo men to play hostile Apache Indians in Stagecoach, encouraged other filmmakers to employ locals, thereby creating a fairly steady source of jobs. In honor of his success in promoting Monument Valley, a lookout point was named after him.

Beyond Westerns, Monument Valley has been the venue of films like 2001: A Space Odyssey, Easy Rider, Eiger Sanction, Thelma & Louise (1991), Mission Impossible II, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade and, most recently, The Lone Ranger.

Monument Valley’s scenery has also been used to promote Marlboro cigarettes in magazine and newspaper ads, to enliven the cartoon strip Krazy Kat, to enhance the Nintendo game Code Name: Steam and to jazz up the record album cover of a rock band, the Eagles.

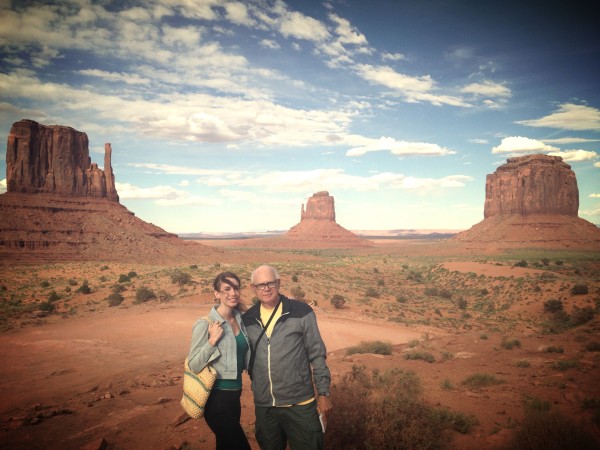

These kaleidoscopic images collided in my brain in a phantasmagoric explosion of colors and hues when I finally reached Monument Valley. The majority of visitors explore the park by car via an 18-mile loop road where they can pause to admire the scenery. My daughter and I signed up for a two hour guided tour, which takes you to secluded places on private roads off-limits to other visitors.

We were amazed by the awesome formations — East and West Mitten, Three Sisters, Totem Pole and other ethereal mesas, buttes and spires that have graced countless coffee-table books.

The flora was diverse. As I discovered, the valley is rich in vegetation — cactus, juniper trees, stunted cedars, tumble weed, sagebrush, wild flowers and yuccas. Local inhabitants use some of these plants as pharmaceuticals. “This is our pharmacy,” our Navajo guide said.

As the tour proceeded, we decamped at a hogan, a Navajo hut fashioned out of red mud and supported by cedar posts. For a few minutes, we watched an impassive woman weaving intricately-designed blankets, some of which fetch thousands of dollars.

At a shady overhang exposed to the sky by a gaping hole on the ceiling, our guide turned entertainer, singing a plaintive love song to illustrate courtship rituals among the Navajos. It was an unusual way of ending a tour of Monument Valley, but on second thought, his impromptu performance reminded me of a saccharine scene out of a grade-B 1940s Western and was thus fully in keeping with the valley’s inextricable association with Hollywood.