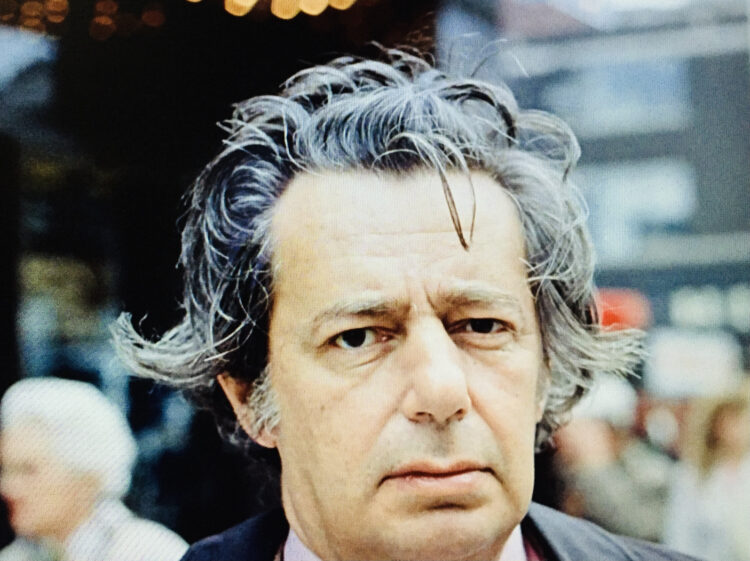

Nineteen years before Mordecai Richler’s death in 2001, the National Film Board of Canada made a short documentary about this prominent Canadian novelist, journalist and screenwriter. Mordecai Richler: The Writer and His Roots, directed by Claire Helman, was released in 1983. This 21-minute film can be accessed online during May, in honor of Canadian Jewish Heritage Month.

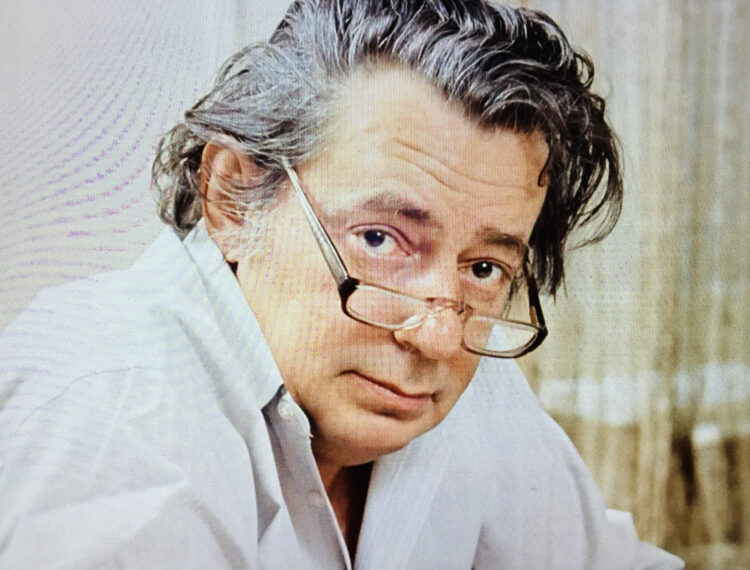

Richler, one of the narrators, expounds on his craft, recalls his youth, and reads excerpts from his books. It’s a bracing, though somewhat disjointed, excursion into the life of one of Canada’s finest writers.

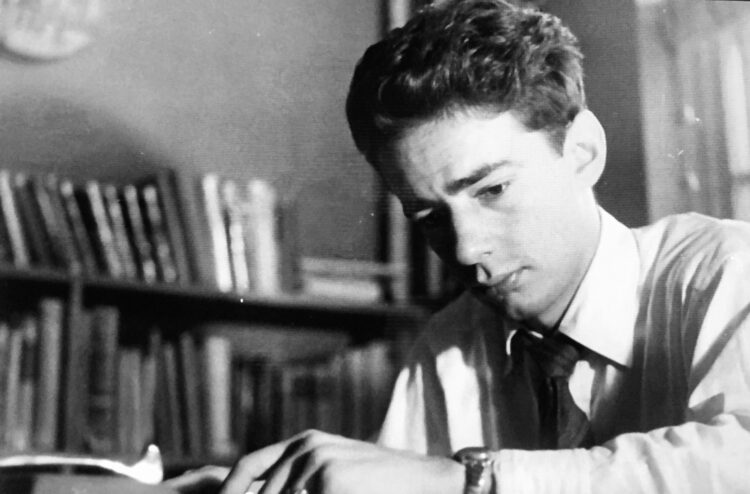

He begins on a self-deprecating note. “The truth is, I just managed to scrape through high school, having put too much time in pool rooms and not enough time in classrooms.”

Richler, born in Montreal in 1931, attended a Jewish parochial school when he was a child, and much to his misfortune, his teacher was a surly, impatient man who disliked children.

He studied at Baron Byng High School, whose enrollment, he notes, was almost one hundred percent Jewish. Some of its graduates were quite successful, becoming doctors, dentists, lawyers and accountants. But on balance, he dismisses his 1948 graduating class in one brusque sentence: “We were not a promising or engaging bunch.”

When he was accepted into Sir George Williams University, from which he would drop out, a guidance counsellor asked what career he hoped to pursue. A writer, he replied. As the counsellor suggested, he could not expect even a modicum of financial security from this craft. Richler proved him wrong.

As the film unfolds, Richler asks a rhetorical question: Why do I write? Paraphrasing the British novelist George Orwell, he lists the reasons: sheer egoism and the desire to be seen as clever, well known and remembered after death.

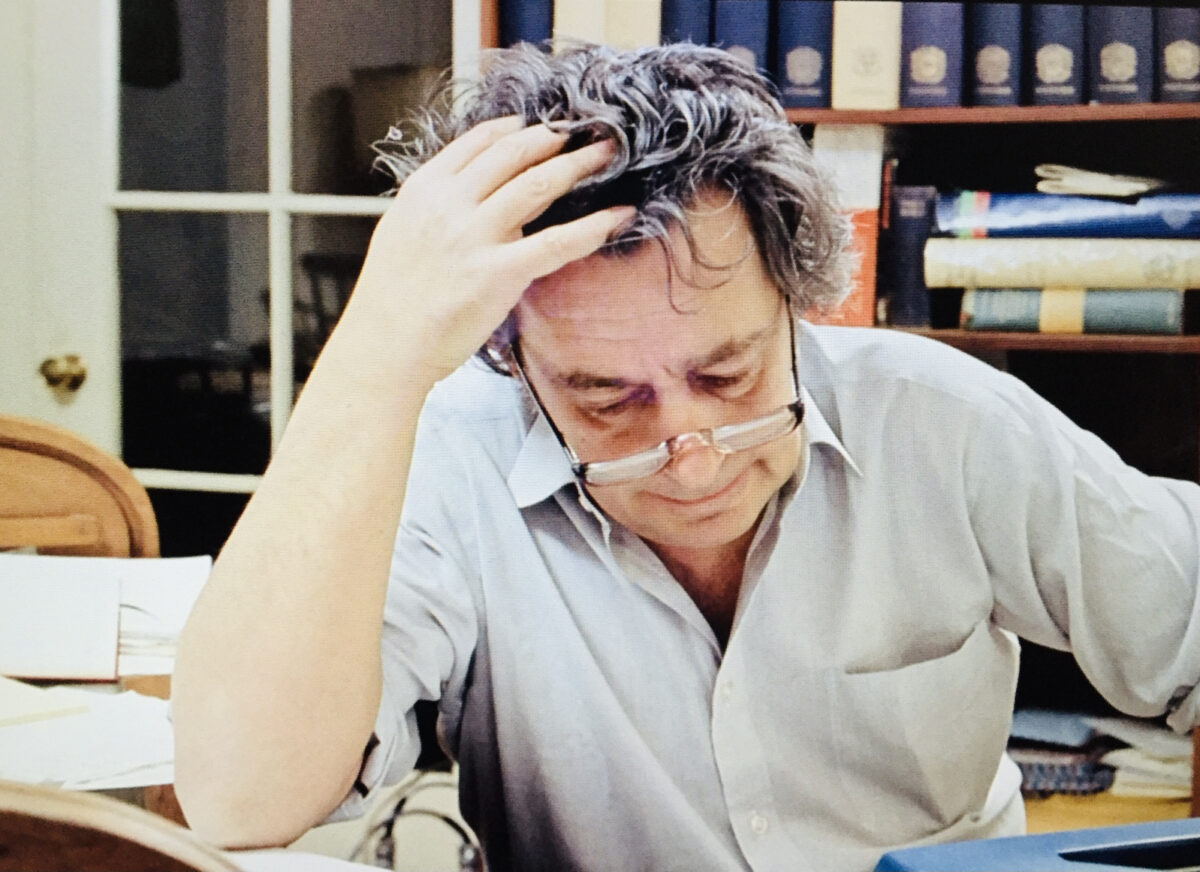

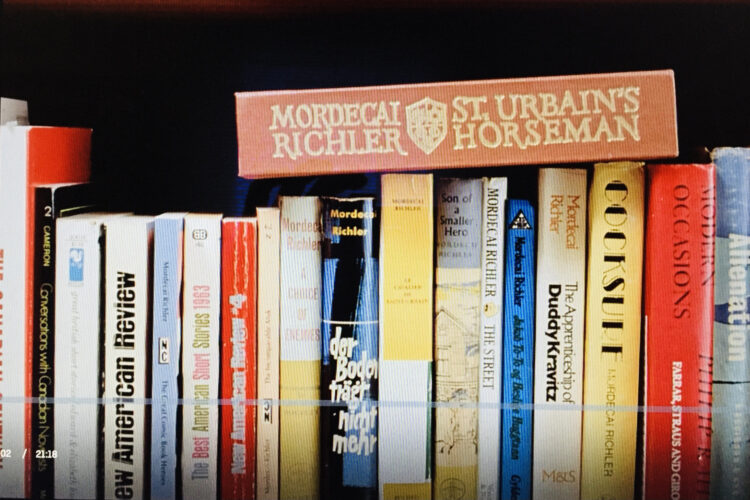

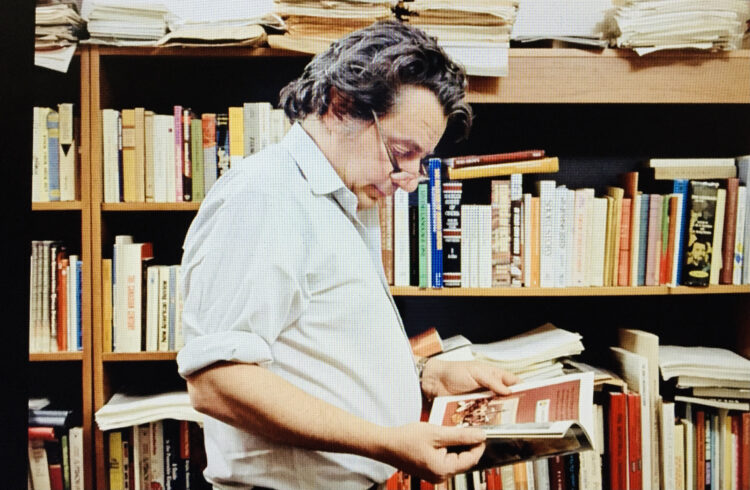

As much as he enjoys being a writer, Richler admits that the production of a novel is a “horrible and exhausting struggle.” Looking back, Richler thinks that St. Urbain’s Horseman (1970) was the most difficult of his novels to write. Five years in the making, it runs to 180,000 words.

The film at this point segues into his past.

Richler’s Montreal was far from the Anglo-Saxon and French Canadian mainstream. The son of European immigrants, he was raised on St. Urbain Street, in the Mile End district, a Jewish working-class enclave. His father was a scrap metal dealer. His mother goes unmentioned.

Fred Rose, a communist, represented Richler’s riding in parliament. Accused of being a Soviet spy, he was arrested and stripped of political office.

Richler’s first published novel, The Acrobat (1954), appeared when he was only 23, and was translated into five languages. His aunt was unimpressed, figuring there must have been a shortage of books in these countries. His father asked whether it was about Jews or “ordinary people.”

Richler understands his father’s question. All too often, Jews of his generation applied one universal standard for everything under the sun: Is it good for the Jews? As he grew older, Richler was increasingly preoccupied by the fate of Jews, a theme he incorporated into his works.

In his early 20s, he travelled widely, spending a lot of time in Spain and France. Settling down in Britain, he turned to journalism and screen writing for a livelihood. Yet he continued with creative writing. The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1959), his most successful novel till then, was converted into a movie starring the young and unknown Richard Dreyfus.

He digresses by saying that a writer should be judged by his work and not his personality. Judging by my two interviews with him over a ten-year period, he was grumpy, remote and easily bored.

When he is not busy writing, he’s a husband and the father of five children, he says.

Richler lives in an affluent part of the city, close to the McGill University campus on Sherbrooke Street. His old neighborhood around St. Urbain Street has changed in terms of its demography. Jews fled long ago and were replaced by, among others, Portuguese and Vietnamese immigrants. Yet he still feels rooted to St. Urbain Street and always strives to convey its true essence in his works.

In parting, Richler confesses that his fondest dream is to write a novel that will endure and be remembered long after he has left this vale of tears. “I keep on trying,” he says laconically.