Sports and politics collided in 1936, when the winter and summer Olympic Games were held in Germany.

Opponents of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime called for a boycott, believing that participation would be a validation of Germany’s openly antisemitic policies and practices. Critics blasted this approach, claiming the Olympics fostered national pride and unity as well as international understanding and amity.

In Canada, the clash between these competing visions played out in a cacophonous debate broadly pitting the Jewish community and left-wing organizations against the Canadian Olympic Committee and the federal government of Prime Minister Mackenzie King.

These duelling points of view are explored in minute detail in More Than Just Games: Canada and the 1936 Olympics, a fine scholarly work written by Richard Menkis and Harold Troper and published by the University of Toronto Press.

Canada ultimately sent a team of athletes to Garmisch-Partenkirschen and Berlin, the site of the winter and summer Olympics. That’s really besides the point, though. What’s important here is the process that prompted Canada to take part in a sporting event that proved to be a glittering showcase for Nazi Germany.

Berlin was chosen as the venue for the summer Olympics two years before Hitler’s accession to power in 1933. They had been scheduled to take place in Barcelona, but with that city mired in a deepening political crisis that would set off the Spanish Civil War, Berlin was given the nod.

As the authors point out, the Nazi movement had been contemptuous of the Olympics, with Hitler having dismissed the 1932 summer Games in Los Angeles as a nefarious exercise in race degradation and “an invention of Jews and Freemasons.” Julius Streicher, the publisher of the rabidly antisemitic newspaper Der Sturmer, dismissed the Olympics as an “infamous” spectacle dominated by Jews.

Cognizant of the Nazis’ dismissive attitude, the German Olympic Committee lobbied Joseph Goebbels, the new minister of propaganda. Acutely aware that the Olympics could be a brilliant public relations coup for a reborn Germany, he enthusiastically endorsed them. Hitler also put his full weight behind the Olympics.

But there was a problem.

German Jews, being non-Aryans, already had been ejected from sports organizations, federations and clubs. The purge was so sweeping that Daniel Prenn, one of Germany’s finest tennis players, was expelled from the German Davis Cup squad.

“The Nazi ethnic cleansing of German sports obviously did not comport with the Olympic ideal of open athletic competition free of racial or religious discrimination,” write Menkes and Troper, who respectively teach at the University of British Columbia and the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto. “This being the case, would the International Olympic Committee allow the Olympic Games … to proceed as planned. And equally important, would the rulers of the new Germany permit German athletes and officials to participate in, let alone host, an Olympic Games that would have athletes of different races and religions compete as equals?”

To fob off critics, the German Olympic Committee announced that there would no discrimination in the treatment of visiting athletes and that German Jews would not be excluded from the German team.

German diplomats in Canada publicized these pronouncements. The German consul in Winnipeg, Heinrich Sellheim, went as far as to claim, in an interview with the Yiddish newspaper Dos yidishe vort no less, that Germany’s Jewish policy was misunderstood.

The newly revived Canadian Jewish Congress supported an Olympic boycott, but its executive director, H.M. Caiserman, refused to cooperate with communists and communist-front groups. It’s questionable, however, what Congress achieved, since it was understaffed and underfunded. During this period, Congress focused its limited resources on the economic boycott against Germany and on combating antisemitism in Canada, of which there was no shortage.

Newspapers in Canada carried reports on the rising tide of antisemitism in Germany, but declined to support a boycott. Lou Marsh, the syndicated sports columnist of the liberal Toronto Star, argued that Nazi racism was an internal German matter. Elmer Ferguson, the lead sports writer for the Montreal Herald, was virtually the only major Canadian sports journalist who supported a boycott.

Winnipeg city council voted to withhold financial support for Olympic-bound athletes, while Toronto’s progressive mayor, Jimmy Simpson, voiced opposition to contributing city funds to the Canadian team.

In the meantime, the Canadian government sought to increase trade with Germany.

As the winter Games drew nearer, the Nazis temporarily moderated coarse public displays of antisemitism. But these cynical moves were offset by the spectacle of storm troopers assaulting Jews on one of Berlin’s most fashionable streets, Kurfuerstendamm, and by the passage of the Nuremberg Laws, which stripped Jews of their German citizenship and forbade intermarriage.

Press coverage in Canada of these developments was sharply negative, but it had no effect on the manner in which Canadian reporters covered the winter Games in Bavaria. They were dazzled and distracted by the alpine scenery, the old world charm of the region and the hospitality of the local inhabitants.

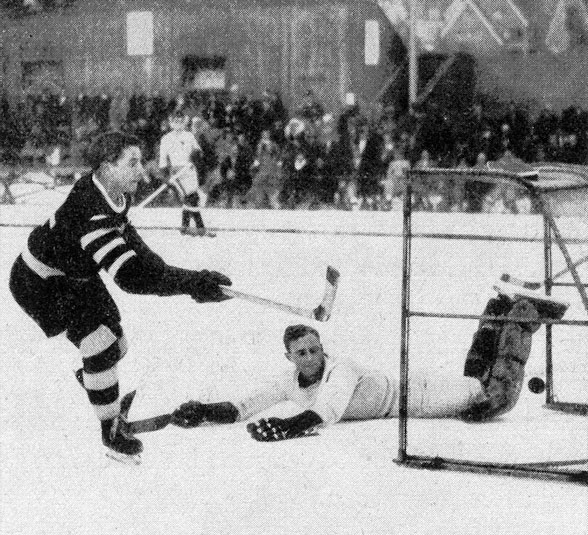

They were also impressed that the most talented member of the German hockey team, Rudi Ball, was Jewish. In fact, he was partially Jewish. Ball only agreed to play to protect his family from Nazi threats of retribution.

Avery Brundage, the head of the American Olympic Committee, hailed the winter Games as a resounding success, thereby dooming efforts to boycott the summer Olympics.

The Canadian Olympic team was received with pomp and ceremony in Berlin. Its sole Jewish athlete, Irving Meretsky, was a basketball player. “If Meretsky was struck by the plight of Jews in Nazi Germany, he was the exception,” the authors write. “Most of the Canadians were swept up in a friendly and agreeable environment that welcomed Olympic athletes. If anything, the cordiality of their German hosts overwhelmed the Canadian team.”

A handful of Canadian athletes, such as the Jewish boxers Sammy Luftspring and Norman Yack, boycotted the Olympics altogether, participating instead in the Barcelona counter-Olympics.

The Berlin Games went off without a hitch, and Brundage was quick to trumpet the inclusion of Helene Mayer — a half-Jewish fencer on the German team — as a sign of its inclusiveness. “Mayer played her part well,” observe Menkis and Troper sardonically. She won silver in women’s individual fencing, and upon receiving her medal, she extended her arm in a stiff Nazi salute.

The Canadian Olympic Committee heralded the Berlin Olympics as a portent of global fellowship, little realizing that the brutal Nazi regime had pulled the wool over their eyes.

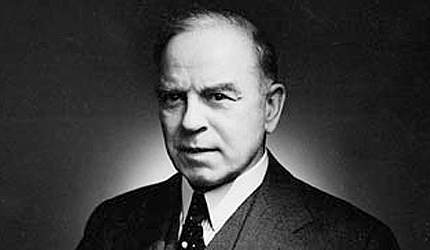

In 1937, Mackenzie King paid an official visit to Germany, and he was swayed by Hitler’s charisma. “My sizing up of the man as I sat and talked with him was that he is really one who truly loves his fellow-man and his country …” he would write.

Like the Olympic committees which chose not to boycott the winter and summer Games in Germany, King was laboring under a grand illusion.