European Jews trapped in Nazi ghettos and concentration camps during the Holocaust were dependent on life-saving shipments of food, medicine, clothing and money transfers for sheer survival. These parcels and transfers, donated by relatives, friends and Jewish institutions, were morale boosters that prolonged the lives of the recipients. In some cases, they arrived too late or were stolen. Incredibly enough, they continued to be sent throughout World War II.

This little-known footnote in the annals of the Holocaust is thoroughly examined in More Than Parcels: Wartime Aid for Jews in Nazi-Era Camps and Ghettos, a compendium of academic essays edited by Jan Lanicek and Jan Lambertz and published by Wayne State University Press.

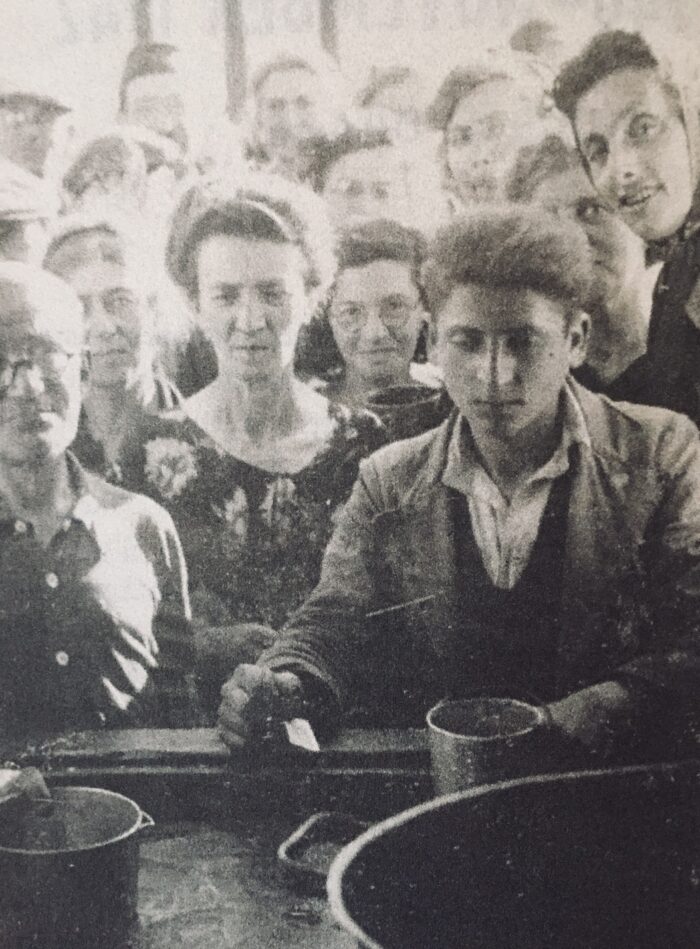

Schemes to assist Jews in distress were necessary due to Nazi Germany’s genocidal policy of starvation. In the Warsaw ghetto, for example, upwards of 60 percent of its inhabitants subsisted on a starvation diet that often led to their deaths. Hence the urgent need for relief parcels.

These packages, often weighing no more than a few pounds, “could extend the lives and health” of Jews for a while at least, writes Lambertz, a researcher at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. “For Jews all over occupied Europe, the ‘parcel economy’ provided critical emotional sustenance in the face of grief and peril.”

German officials permitted food parcels into some of the major ghettos until at least early 1941. The entry of the United States into the war and the tightening of the Allied blockade against Germany greatly decreased but did not stop this flow. Indeed, the prospect of an Allied victory in the last two years of the war convinced some German allies, namely Romania, that it was in their vested interest to permit humanitarian aid to Jews.

In still other cases, the relief project may have functioned as “a kind of decoy measure,” masking the murder of Jews in Nazi extermination camps, Lambertz adds.

This caveat notwithstanding, the parcel economy was of the utmost importantance to Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe. Until 1941, the Lodz ghetto in Poland received some 64,000 money transfers and 14,000 packages from abroad and 135,000 domestic parcels. Those that did arrive were “a drop of relief in an ocean of agony,” says Lanicek, a professor of European and Jewish history at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. Sadly, most packages arrived after the majority of their intended Jewish recipients had been deported and killed.

Polish Jews who fled to the Soviet Union after Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939 were often penniless and depended on relatives and friends in the western half of Poland for sustenance. One such refugee, Menachem Begin, the future prime minister of Israel, said these packages “warm out hearts.”

After Polish escapees gradually found their footing in the Soviet Union, relief packages began to move from east to west, writes Eliyana Adler, a professor of history and Jewish Studies at Penn State University. By one estimate, 84 percent of the packages reaching the Warsaw ghetto before the summer of 1941 came from the Soviet Union.

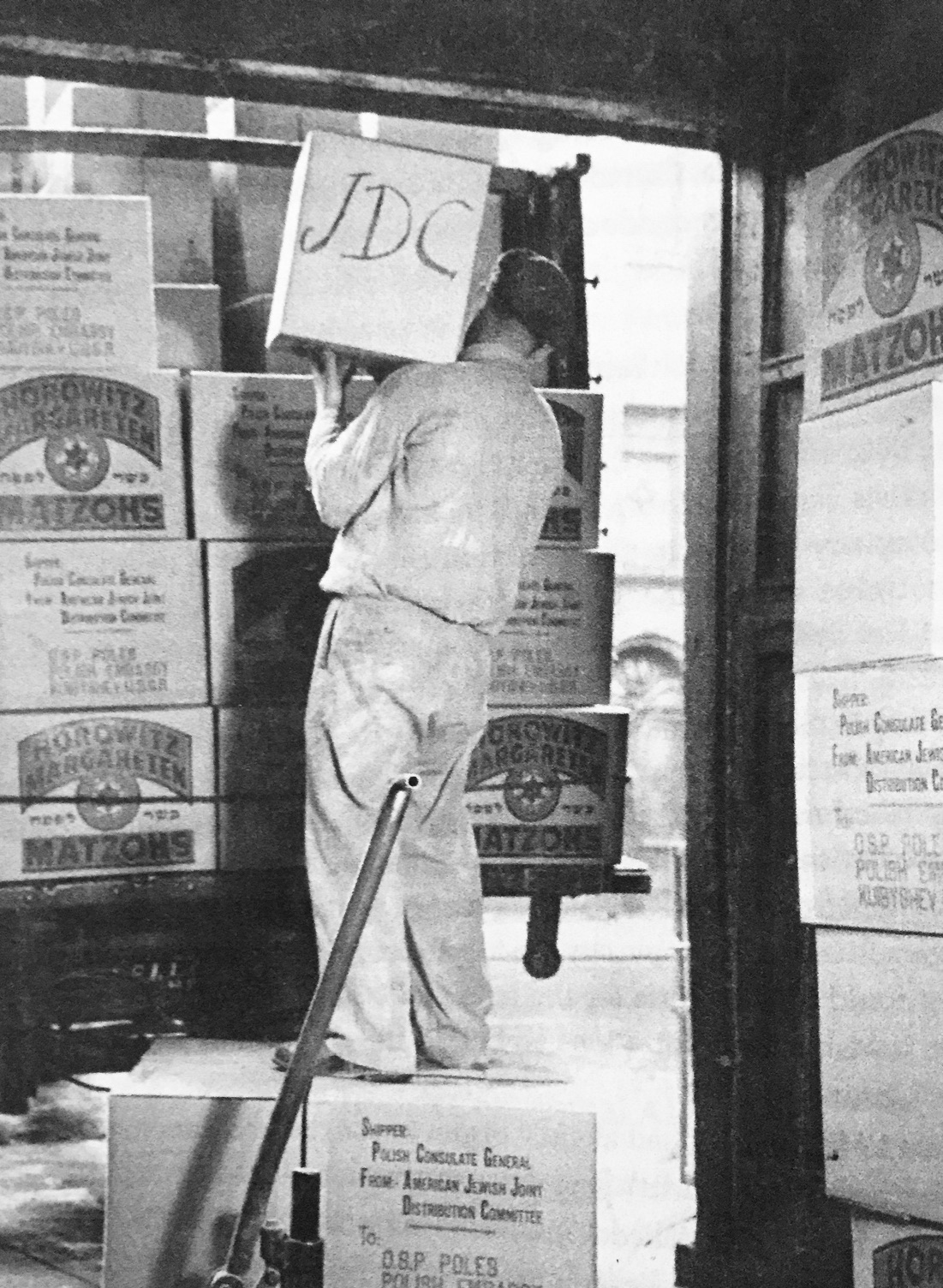

The American Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) played a key role in aiding Polish Jews and their families. In addition, the JDC organized soup kitchens in ghettos and financed programs in children’s homes, old age homes and hospitals. It also dispatched food and medical supplies to the Plaszow concentration camp, near Krakow, and the Polish-government-in-exile’s collection points in Tehran.

The JDC collaborated with the Red Cross in providing relief, says Gerald Steinacher, a professor of history at the University of Nebraska. While the JDC provided financial support and supplies, the Red Cross transported and delivered food.

Jewish activists such as Abraham Silberschien, a Polish Jewish lawyer who found himself in Switzerland by happenstance when the war erupted, worked with the World Jewish Congress to help Polish and French Jews in duress. This facet of the relief scheme is explored by Anne Lepper, who works at Yad Vashem’s International School for Holocaust Studies.

Lanicek, in his essay, writes of the efforts of the Board of Deputies in Britain and the Polish Relief Committee in Lisbon to send 27,000 parcels to Poland in 1943.

During the final months of the war, aid for Jews in German concentration camps arrived from neutral Sweden. One of the key players in this program was Hillel Storch, a Latvian Jew who lived in Stockholm as a refugee, says Pontus Rudberg, a Swedish historian affiliated with Uppsala University.

The War Refugee Board, a U.S. agency established by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1944, was instrumental in sending essential supplies to the needy in concentration camps in Germany, says Rebecca Erbelding, a historian at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. One of its recipients, Dora Burstein, received a cardboard box filled with food while imprisoned in the Ravensbruck concentration camp. Although sent by the War Refugee Board, the box bore the markings of the Red Cross.

Detainees in Vichy camps in France were poorly nourished, but famine was not a problem thanks to the relief provided by international organizations. This topic is examined by Laurie Drake, who wrote a PhD on it at the University. In her estimation, 40,000 of the 50,000 individuals held in 25 camps and 60 smaller holding centers were Jewish.

Some of the most extensive atrocities during the Holocaust took place in Transnistria, an area in the southwestern Soviet Union occupied by Romania. From 1941 to 1944, hundreds of thousands of local and Romanian Jews were murdered here or left to die, says Stefan Cristian Ionescu, a Romanian scholar of the Holocaust. Paradoxically, Jews deported to Transnistria had the highest survival rate in areas controlled by Germany and its allies.

Ion Antonescu, Romania’s antisemitic ruler from 1940 onward, encouraged Romanian Jews to send supplies to Jews in Transnistria because he calculated that Germany might lose the war. Certain that Jews wielded immense power in Allied capitals, he believed he could save himself by moderating his antisemitism. He miscalculated. Having been convicted as a war criminal, he was hanged after the war.

In this case, justice prevailed.