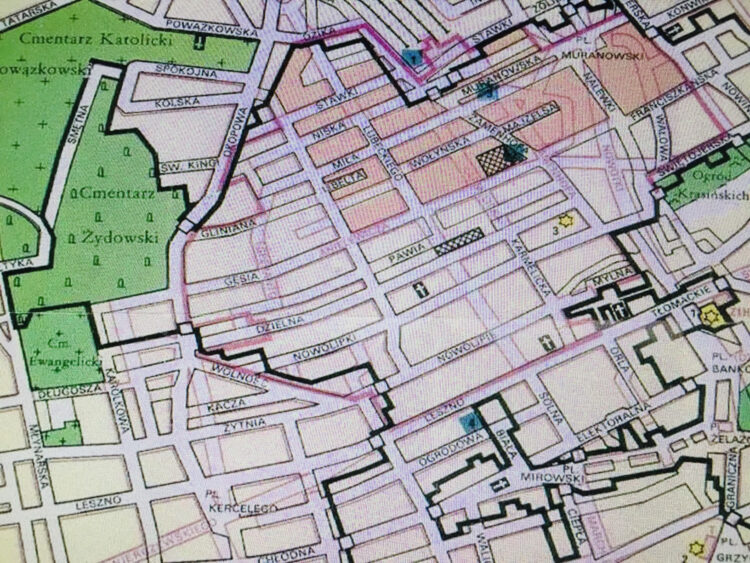

Approximately 200,000 Jews lived in Warsaw’s Muranow district, the hub of Jewish life in Poland, before World War II. Forming the core of the Nazi ghetto after 1940, it served as a conduit from which Jews were deported to the Treblinka extermination camp as the Holocaust unfolded.

During the doomed but heroic 1943 uprising, which was mercilessly crushed, the Germans set fire to the ghetto. As flames lit the sky in blood red and black soot, Muranow was burned to the ground, leaving mountains of rubble.

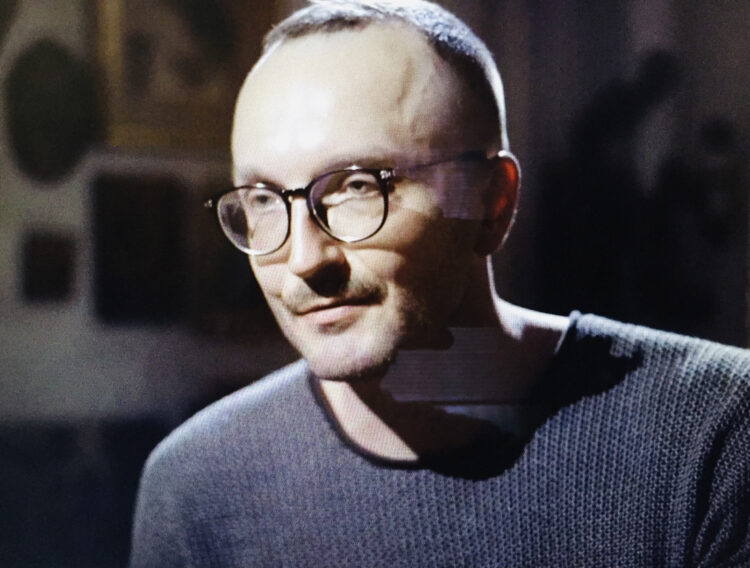

The Polish government rebuilt the neighborhood after 1945. Construction workers often found human bones and remains mixed in with the concrete, says Chen Shelach, the director of Muranow, a chilling documentary to be screened online at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival, which runs from June 3-13.

Shelach, an Israeli, dedicates the movie to his grandfather, Tuvia Knurowicz, a father of three who presumably lived in Muranow. He vanished near Warsaw on September 1, 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland, and his body was never found. He was among the three million Polish Jews who perished in the Holocaust.

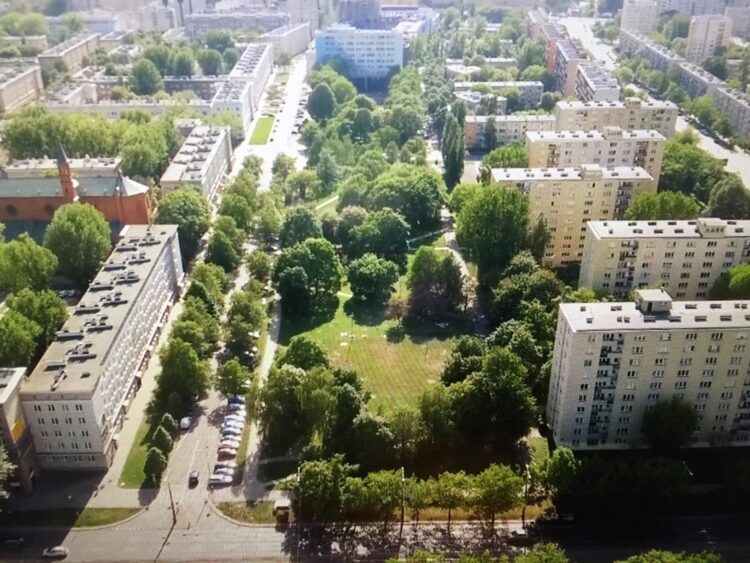

In his film, Shelach interviews residents of contemporary Muranow, a grey, non-descript neighborhood of drab tenement buildings. He juxtaposes it with graphic archival photographs and file footage of Muranow before, during and after the war.

Katarzyna Żak, the director of the Warsaw Museum Library, was born in Muranow. The pre-war version is so embedded in her mind that she has dreams about it.

Zuzanna Radzik, a journalist and researcher, inherited her apartment in Muranow.

“It’s a perfect neighborhood for the dead and the living,” she says. “I know the meaning of Muranow, but if I think about it too much, it will drive me crazy.”

Friends who moved out of her building explained that they didn’t want to drink the tap water from a pipe running from the nearby Jewish cemetery.

Maciej Mahler, an architect, thinks his flat is spooked by Jewish ghosts. Referring to old Muranow as a “lost civilization,” he believes that people in new Muranow fear that Jews will return to reclaim the land on their properties.

Elzbieta Bednarska, an administrator who has lived in Muranow all her life, stands on the roof of a building and tells Shelach that nothing remained of it in 1945 except one lone church.

As Shelach talks to an interviewee in his flat, another man enters and asks for Shelach’s identity. “I thought it was these fucking Jews,” the intruder blurts out after being informed that a film crew is making a documentary about Muranow.

One of its most unusual residents, Matan Shefi, is a former Israeli Navy submarine commander whose ancestors hail from Muranow.

Israeli youth delegations usually pause here to pay homage to the Warsaw ghetto fighters, who are memorialized in Nathan Rappoport’s imposing monument.

Rami, the Lebanese owner of Felafel Beirut, a Middle Eastern restaurant in Muranow, is shocked to learn that Muranow was built on ruins of a Jewish neighborhood.

Shelach points out that the army uses it as a venue to highlight Polish victimhood, and that right-wing nationalists have marched through it shouting, “Poland belongs to Poles.”

Muranow has gone through a major transformation since the war, but the echoes of the past still rumble through it, as he suggests.