It’s a little-known fact. France, next to Israel, has the greatest number of Jews and Muslims living side by side in any country in the world.

France is home to four to six million Muslims and 500,000 to 600,000 Jews. Since a significant proportion of its Muslim and Jewish citizens hail from the same countries — Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia — they live together in some neighborhoods, share certain linguistic and cultural traditions and have a common experience of displacement, Maud S. Mandel contends in her comprehensive book, Muslims and Jews in France: History of a Conflict, published by Princeton University Press.

Although these factors may bring Jews and Muslims closer together in mutual understanding, the relationship between them is fraught due to tensions arising out of the Arab-Israeli dispute and the emergence of Islamic radicalism.

Last year, an Islamic State sympathizer killed several Jewish shoppers in a kosher supermarket in Paris. In 2012, a Muslim extremist fatally shot a rabbi and three Jewish children at a Jewish school in Toulouse. And in 2006, Ilan Halimi, a 23-year-old Parisian Jew, was kidnapped and murdered by a Muslim gang.

Judging by these events, French Muslims and Jews appear to be on a collision course. Mandel, a professor of Judaic studies and history at Brown University, challenges that assumption. She regards it as a “gross simplification of the much richer and more varied range of Muslim-Jewish relations in France.”

Realizing, however, that Jews and Muslims are directly influenced and affected by the perennial Arab-Israeli imbroglio, Mandel incorporates this source of strife into her final conclusions.

France’s Muslim population, as she reminds a reader, is diverse. Consisting of immigrants from North Africa, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon and West Africa, the Muslim community was augmented by newcomers from sub-Sahara Africa, Central Asia and Bosnia in the 1990s.

The first Jewish immigrants from North Africa and the Levant arrived in France before and after World War I. And because they had more in common with Arabs than with Western Jewish immigrants or native-born Jews, they often chose to live in heavily-Muslim neighborhoods. In the decades following the proclamation of statehood in Israel, still more North African Jews migrated to France.

By the late 1940s, the growing, if muted, support for Zionism among French Jews was mirrored by “a mounting interest in the Palestinian question among Algerian Muslim nationalists.”

Nevertheless, as Mandel says, “the issue did not become a central social or political question for most Muslim immigrants. Living on the margins of their host nation and absorbed with the daily tasks of providing for themselves and the families they had left behind, most did not involve themselves in the domestic or international controversies of the day.”

Politically active Muslims in France, such as the dockworkers of Marseille, deviated from the norm and immersed themselves in the incendiary politics of the Middle East. In June 1948, a month after Israel declared its independence, they refused to load freight onto ships transporting Jewish immigrants or arms to Israel.

Strangely enough, no such protest erupted when the Altalena — an Irgun vessel crammed with 1,000 Jewish volunteers and a stockpile of weapons — sailed from Port-de-Bouc, 45 kilometers from Marseille, to Palestine in the same year.

By Mandel’s estimation, 25,000 Jews travelled through Marseille — France’s largest port and its gateway to the Mediterranean — en route to Palestine from 1946 to 1948. “France’s willingness to condone the passage of Jewish people and arms through (Marseille) became part of a criticism of France’s relationship with its Muslim subjects and citizens,” she says.

France’s decision to turn a blind eye to Jewish immigration to Palestine was a considerable source of bitterness in the North African nations it had colonized, Mandel notes.

During the period of France’s disengagement from North Africa, the Jewish community was split. Some Jews called for dialogue and cooperation with Muslims. Still others focused on “Jewish victimization” at the hands of Arabs and dismissed dialogue as an option. According to Mandel, the second perspective would dominate much of mainstream communal discourse by the mid-1960s.

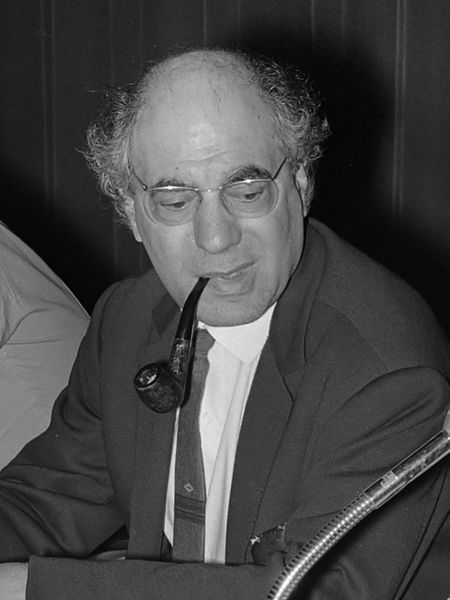

The Six Day War solidified pro-Israel opinion among Jews in France. A vocal minority of Jews, particularly those associated with the Communist Party, criticized Israel as the aggressor and slammed Israel’s occupation of the newly conquered territories. Maxime Rodinson, a Jewish Middle East scholar, emerged as one of Israel’s harshest critics.

Algeria’s role as a prime supporter of the Palestinians, before and after the 1967 Six Day War, was not lost on Algerian immigrants in France. They backed President Ahmed Ben Bella’s decision to train Palestinians in guerrilla warfare. His successor, Houari Boumediene, continued Algeria’s support the Palestinians. By 1968, Algeria had become the biggest supplier of arms to Fatah after China.

A year after the outbreak of the Six Day War, a riot broke out in the Parisian immigrant neighborhood of Belleville. Jewish and Muslim political and religious leaders worked tirelessly to restore calm, but Jewish newcomers in Belleville who had lived in Tunisia during the anti-Jewish riots a year earlier bore resentments against Arabs.

After 1967, French universities became hotbeds of anti-Zionist rhetoric. As Mandel puts it, “French radicals, North African Muslim students and Palestinian representatives created alliances that brought the Palestinian issue to French public attention.”

Violent confrontations between Muslim and Jewish youths exacerbated tensions.

“Jewish and Muslim leaders urged moderation to ensure collective safety and prosperity,” she writes. “Moreover, the Jewish leadership continued to see the Muslim immigrant population as distinct from their spokesmen.”

Interestingly enough, the controversy over the Muslim head scarf prompted France’s chief rabbi, Joseph Sitruk, who died recently, to join Christian clerics in support of Muslim women who preferred to wear a head covering. “For him, defending the head scarf was equivalent to defending the yarmulke,” observes Mandel.

French Muslim youths were radicalized by the second Palestinian uprising, which broke out in September 2000. “Increasing links between young French Muslims and their co-religionists in Palestine brought the Middle Eastern conflict to France,” she says. “French Muslim youth (began) identifying with the Palestinian cause as a way to express their own social frustrations. For those who feel marginalized and disenfranchised in France’s poor urban neighborhoods, the Palestinian struggle for recognition has taken on symbolic meaning, allowing anger at Israel to become increasingly entangled with anti-Jewish stereotypes.”

In closing, Mandel strikes a pessimistic note: “Muslim-Jewish conflict is likely to remain a salient feature of French political life for the foreseeable future.”

Sadly enough, she’s right.