My mother turned 100 today.

It’s an auspicious moment leavened by sadness.

By any yardstick, she has beaten the odds. She might have been a victim of the Holocaust, like nine out of 10 Polish Jews. She has battled health problems all her life. And now her body and mind have succumbed to the frailties of time and the ravages of dementia.

So as I celebrate her birthday, wishing her all the best, I feel torn. I rejoice in her longevity but I’m saddened by the physical and mental burdens she carries.

Despite my misgivings, I know she’s in a good place. My father, who reached the age of 100 last year, is there to keep her company. He’s also a Holocaust survivor, a veteran of the Polish army, decimated by Germany’s invasion on September 1, 1939.

That they’re still together as a couple, their spats and arguments notwithstanding, is remarkable. There are precious few couples like them. The vast majority of Holocaust survivors have already passed on. But they’re still here, ailments and all.

Two Holocaust survivors who’ve endured and passed the age of 100.

I’m thankful they still live in their own home, a condominium in north Toronto, rather than in an impersonal nursing home. And I’m grateful they’re well looked after by caregivers, who seem dedicated to their welfare, and by my two sisters, who attend to their needs.

My mother was born in the second year of World War I, seemingly an eternity ago. She goes by three first names — Genia, Golda or Jean. When she speaks Polish, she’s Genia. When she lapses into Yiddish, she’s Golda. When she uses English, she’s Jean.

We call her “mamo,” the Polish word for mother.

She’s comes from Lodz, a textile town in central Poland. The German army occupied Lodz and proceeded to demonize, terrorize, isolate and murder its Jewish inhabitants in dribs and drabs. Like my father, David, whom she knew before the war, she’s a survivor of the Lodz ghetto. Only five percent of its Jewish inmates survived, and she’s among them. The remainder were deported to Nazi extermination camps in Poland, shot by Nazis or died of starvation or disease. Still others, in utter despair, committed suicide.

When the Germans liquidated the ghetto in August 1944, most members of her family, as well as her first husband, already had been killed. She and her five-year-old son, my brother whom I never knew or set eyes upon, were sent straight to Auschwitz-Birkenau by train. My father suffered a same fate.

My knowledge of her confinement in Auschwitz-Birkenau –which devoured one million Jews — is extremely sketchy. She was always reluctant to discuss this awful period, understandably enough. What I do know for certain is that she was forcibly separated from her beloved son in the first moments of her arrival there.

She never saw him again. Nor did she ever hear his voice again. And this tragedy haunted and tormented her, even at the best of times. She was inconsolable. Not a single day went by without her thinking about him. Try as I might, I can hardly plumb the depths of her heartbreak.

After Auschwitz-Birkenau, my mother was sent to more Nazi concentration camps, including Bergen-Belsen. In April 1945, starved and sick, she was liberated by British troops. By then, she and my father had met again. Like so many survivors who yearned for company and normalcy, they got married, even if they were not temperamentally compatible.

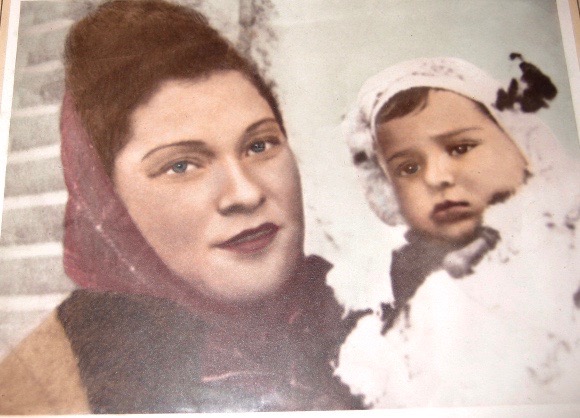

I was born in Bad Reichenhall, an attractive spa in the German Alps. As my mother’s first child after the Holocaust, I was more than just a bouncing, blue-eyed baby. I was resurrection. I was hope. I was a new beginning. And that’s the way she treated me, holding me close to her bosom, showing me off, pampering me.

We arrived in Halifax in the winter of 1948, when I was less than two years old. The Canadian Jewish Congress had persuaded the Canadian government to admit survivors with skills. My father was a tailor and the garment industry in Canada was short of tailors. It was a perfect match.

Of course, my parents never had any intention of staying in Germany, like a some Jewish survivors. Nor, like my two aunts and uncles, were they interested in immigrating to Israel, which was fighting for sheer survival in the face of an Arab onslaught.

From Halifax, we boarded a train bound for Montreal. My initial memory of Canada is of a cavernous train station in Halifax or Montreal. My father started work at Stein & Gerson — a manufacturer of ladies’ clothes — almost immediately upon arrival in Montreal. He held his position as a foreman for 20 years.

We lived in cold-water flats off St. Lawrence Boulevard, as it was then called. My father worked hard, but his pay check was paltry. As a result, my parents took in a boarder, an Italian immigrant named Benny, who introduced us to the pungent aroma of Romano cheese and the uplifting arias of Italian opera.

My mother had stomach troubles from the moment she left Germany. When I was five years old, surgeons cut out two-thirds of her stomach, but the surgery was only partially successful. I remember visiting her in hospital.

Being an excellent housewife in an era when women were far more domesticated than they are today, my mother took care of everything, from cleaning and cooking to paying the bills and going to school meetings to assess my progress or lack thereof.

In the early 1950s, we left Montreal’s old Jewish quarter after my parents bought a duplex off Decarie Boulevard. In 1957, we moved into a freshly-built duplex on Bedford Road. We lived on the first floor and rented out the top unit to a car salesman, who effectively paid for our mortgage.

Like the Yiddish-speaking greenhorns of Montreal, my parents rented a summer cottage in the Laurentian mountains, north of Montreal, during our first years in Canada. While we frolicked the days away, he toiled in a hot factory from Monday to Friday. He would arrive in the “country” on Friday evening and go back on Sunday afternoon, refreshed and ready for more work.

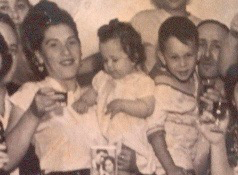

My parents scrimped and saved to put on a big bash for my Bar Mitzvah. There were mountains of food, the liquor flowed and the music played. I delivered my speech without stuttering even once. I considered my feat of eloquence a minor miracle. My mother was not in the least surprised. “I knew you could do it,” she said. She was always there to support and protect me.

Until the age of 16, I gave my mother an obligatory peck on the cheek when I left for school in the morning. When I stopped doing so, she felt hurt and disappointed.

My mother entered the job market after we moved into a bigger duplex in Cote St. Luc, a neighborhood heavily populated by Jews. She worked in a bakery owned by Leon Eisenberg, a fellow survivor. She would bring home cakes and pastries, feeding my appetite for sweets.

She passed her driver’s test, but my father wouldn’t allow her to drive our shiny, second-hand blue and white Chevrolet more than several times. It was a bitter blow, but she got over it.

Although she was a city girl, she liked and appreciated the outdoors and imparted this love of nature to me, a gift I will always cherish.

I was raised on traditional Jewish food with a Polish twist. Thanks to her culinary prowess, I was brought up on delectable staples like sauerkraut-and-potato soup, chicken soup garnished with egg noodles, roast chicken and turkey, meatballs in tomato sauce, dumplings slathered with fried onions, cabbage rolls, gefilte fish, butter cookies and apple cake.

She introduced spaghetti, a gastronomic novelty, fairly late to our house, but once she discovered this exotic dish, there was no turning back. She tried Chinese food in restaurants, but the MSG gave her splitting headaches. She had much better luck with smoked meat sandwiches in delis.

When my father was laid off after his employer declared bankruptcy, a pall of gloom settled over us. How would the bills be paid? The answer was not long in coming. My parents bought a dry cleaning store in downtown Montreal and they prospered, at least for a while.

Around this juncture, I went to London to do a postgraduate degree. When I returned 10 months later, I learned that my father had been shot and grievously wounded in a holdup and that the business had been sold. When I asked why I hadn’t been informed, my mother replied, “We didn’t want to interrupt your studies.” My mother was a great believer in education.

The following year, I went to a kibbutz to study Hebrew and try out Israel. My mother missed me very much, but we corresponded. When my parents visited Israel in 1971, I was dating a young Israeli woman of Polish origin. I wasn’t ready to commit, but my mother told me she had a diamond engagement ring in her purse in case I decided to take my relationship to the next level. It didn’t happen and she was disappointed.

Shortly afterward, I met Etti, a Bulgarian Israeli who was pursuing an MA degree in English literature at Tel Aviv University. We were married in Tel Aviv in 1972. I returned to Montreal almost two years later. Within a month and a half, Etti joined me there. Eventually, we moved to Toronto, where we had two lovely daughters, Mia and Lauren.

In 1981, my parents left Montreal for good, eager to be near me and my sister, Marilyn. Subsequently, my youngest sister, Shirley, settled in Toronto as well. My parents were content in Toronto, pleased by their close proximity to their children. They enjoyed their retirement and watched their grandchildren grow into adulthood.

When dementia tragically took hold of my mother, everything changed. Confined to a wheelchair, she no longer cooks and cleans and has lost her mobility and freedom. She rarely speaks English now, having reverted to her childhood Polish, which I don’t understand. Conversation with her has become virtually impossible.

Her face lights up when she greets me. And when I press my cheek against hers, she gives me a kiss. Having lost her ability to converse, she mutters words, but they usually leave her lips in the form of fragmentary sentences or gibberish. It’s frustrating and infinitely sad for all of us.

My mother, at 100, is not the same vital person she was five or 10 years ago. Imprisoned in a decrepit body, she can’t function normally. The lamentable condition in which she finds herself will only get worse, though I trust she’ll be made as comfortable as possible.

Whatever happens in the near future, Genia Golda Jean is embedded deep in my heart. She’s my mother and I love her.