Nathan Hilu, a visual artist from New York City, refers to himself as a “memory man.” It is a fair description of an eccentric, complex person.

Hilu spent decades drawing sketches of Nazi war criminals who faced justice at the Nuremberg trial in postwar western Germany. His drawings, in crayon and ink, are detailed and expressive and resemble graphic comic strips. Hilu describes his style as “Nathan-ism.”

His drawings, which have been acquired by American museums and the U.S. Library of Congress, are valuable inasmuch as they remind an easily forgetful world of Nazi crimes against humanity, says Eli Rosenbaum, a former U.S. government official in charge of prosecuting Nazi war criminals in the United States.

Hilu, who died in 2019 at a ripe old age, is at the heart of Elan Golod’s intriguing documentary, Nathan-ism, which will be screened at the Hot Docs movie festival in Toronto on May 2 and streamed online from May 5 to May 9.

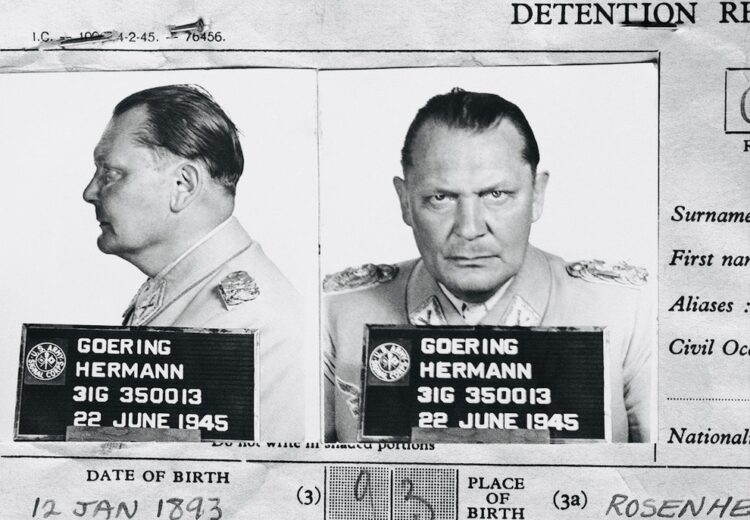

Hilu was apparently a member of a special contingent of U.S. army soldiers assigned to guard high-profile Nazi prisoners such as Hermann Goring, Albert Speer and Julius Streicher before and during the Nuremberg proceedings, the most widely reported trial in history. He was only 18 when he arrived in Nuremberg.

In its April 1970 edition, Jewish Currents magazine published Hilu’s account of his days in Nuremberg.

Speer, Adolf Hitler’s armament minister in the final years of World War II, supposedly urged Hilu to document his experiences. Heeding his advice, Hilu began drawing at a feverish pace, churning out a multitude of drawings, which were both primitive and captivating.

Laura Kruger, a New York City museum curator who discovered Hilu, voices admiration of his talents and prolificacy.

Hilu is a talker, and in much of the film, he recalls his one-year stint in the prison. His comments appear against the backdrop of file footage of Nazi Germany and the war.

Hilu’s apparent proximity to the imprisoned Nazis gave him the rare opportunity to engage them in conversations.

Goring, Hitler’s deputy and the commander of the German Air Force, maintained he was only following orders and claimed he did not commit any crimes. At a Christmas service, he sang carols so sweetly that Hilu could barely believe he was one of the architects of the Holocaust. Hilu contends that Goring’s wife, in her last visit in his cell, secretly gave him the cyanide pills that enabled him to commit suicide before his execution.

By Hilu’s reckoning, Speer was the only Nazi defendant who admitted his guilt. He told Hilu that Hitler had made a “mistake” in ordering the mass murder of Jews in Europe.

Hilu says he brought Ernst Kaltenbrunner to the gallows. He was one of ten Nazis to be hanged after the trial.

Hilu, a Sephardi Jew whose ancestors hailed from Syria, submitted his memoirs for publication. The publisher appeared interested in his recollections and drawings, but declined to publish a book because the authenticity of his story could not be verified due to the fact that his record as a soldier was lost in a fire in 1973 that virtually destroyed the army’s archive in St. Louis.

Lori Miller, an archivist, uncovered evidence of his army service, yet she was unable to place him in postwar Nuremberg. Hilu insists he was there. After all, the Nazis he portrayed in his drawings are factual flesh-and-blood figures.

When Golod, an Israeli, gently confronted Hilu about this inconsistency, he grew agitated. “I’m not making up this stuff,” he declared defiantly.

Regardless of whether he was actually in Nuremberg, his unique drawings of the seminal trial have contributed in no small part to the world’s collective memory of it.