With the launch of Operation Barbarossa, Nazi Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Holocaust entered a new and much more deadly phase.

As the German army conquered vast swaths of territory, coming perilously close to capturing Moscow, mobile killing squads, known as Einsatzgruppen, were set loose to murder communist officials and Jews and incite pogroms.

Collaborating with local nationalists who loathed the Soviet regime and hated Jews, the German killers left a trail of death and destruction behind them in the Baltic states — Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia — and in Belorussia, Ukraine and the rest of the Soviet Union.

By the time they had finished their dirty work, they had murdered about one million Jews, leaving an indelible stain on the country.

Their genocidal rampage unfolds in Michael Prazan’s chilling four-part documentary, Einsatzgruppen: The Nazi Death Squads, which is now available on the Netflix streaming network. The film is composed of vintage footage and photographs and interviews with historians, perpetrators and victims.

Germany’s war in the Soviet Union, its bitter ideological foe, was a war of annihilation where no quarter was given. Heinrich Himmler, the SS chieftain, instructed Einsatzgruppen commanders to be merciless.

Four Einsatzgruppen units, A, B, C and D, accompanied the Wehrmacht into the Soviet Union. Three thousand men were attached to these squads, but eventually, 10,000 more were added. We’re not told from what social classes they came from.

We learn more about their superiors, who were ideologically committed to Adolf Hitler’s Final Solution. Christopher Browning, the eminent historian, says that many commanders, like Otto Rasch and Otto Ohlendorf, were highly educated, having earned PhDs.

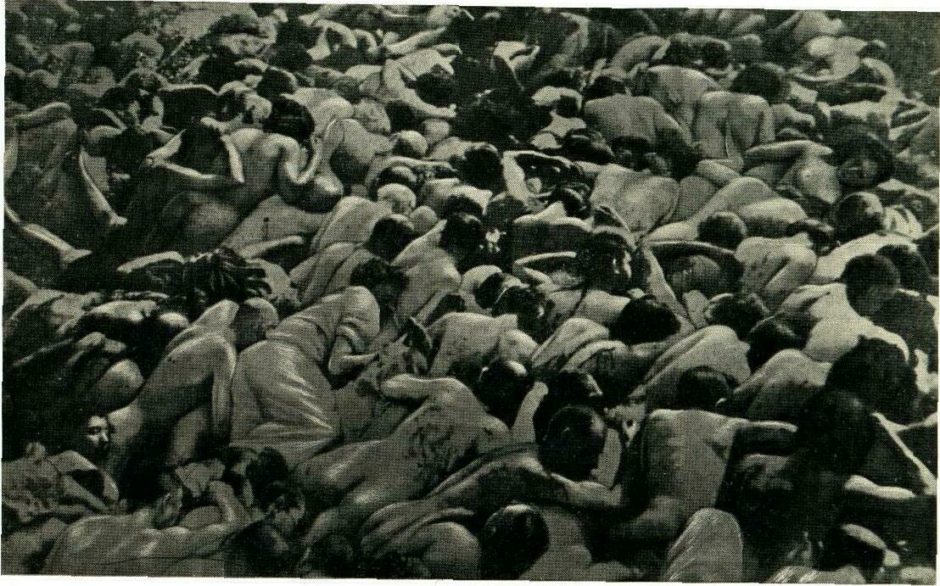

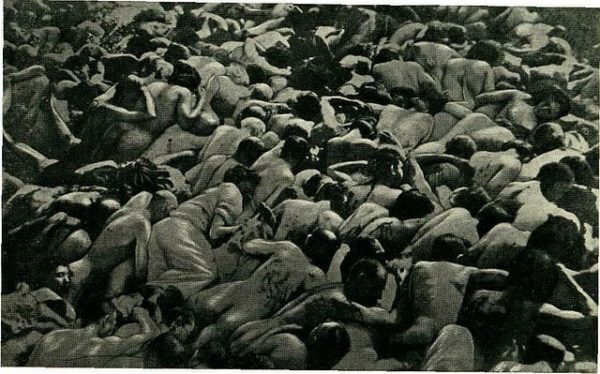

Einsatzgruppen is not for the faint of heart. The blurry scenes of Lithuanian, Latvian and Ukrainian fascists humiliating and beating Jewish civilians in Kaunas, Riga and Lviv leave a viewer reeling with astonishment, disgust and anger. The spare photographs of naked corpses piled up like cordwood and of Jewish women and children being driven to their deaths in open fields and forests are just as sickening.

The personal testimonies of local inhabitants who witnessed the atrocities are compelling. “The Jews didn’t know they were about to die,” says Anatoli Lipinski, a Ukrainian. Another eyewitness, a Lithuanian woman, chuckles inappropriately as she recalls certain incidents. Given the long history of antisemitism in these areas, it’s hard to tell whether these witnesses are sympathetic, hostile or merely indifferent to their former Jewish neighbors.

The perpetrators, some caught by hidden cameras, have their say, too. A Lithuanian claims he acted mercifully by shooting parents before children. He recalls German overseers walking over corpses to ensure they were dead.

The victims, all Jews, live with terrible memories. A woman who was sent to Transnistria, controlled by the pro-German Romanian army, maintains that the majority of Romanians she encountered behaved like “animals.” A man who survived mass executions remembers the flames that lit up the Ponary forest after the Germans dug up masses of corpses and burned them to dispose of evidence.

Though utterly cruel and irretrievably inhumane, the killers were ultimately affected by their harsh conditions. Some, suffering from psychological problems, were sent back home to Germany to recuperate.

Realizing that the Einsatzgruppen method of killing Jews through mass shootings was psychologically problematic, time consuming and inefficient, the Nazis began using gas vans to carry out their diabolical program of extermination. When that method was judged to be a failure, death camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau and Sobibor were built to murder Jews on an industrial scale.

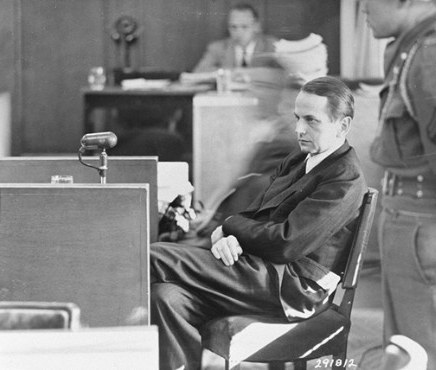

With Germany’s defeat, Einsatzgruppen commanders fell into the hands of the Allied victors and were put on trial. Two were sent to the gallows, but the rest received relatively lenient prison sentences and then released.

So much for justice.