Twenty one years ago, a historic conference in Washington, D.C. ended with representatives of 44 governments endorsing a set of principles designed to assist the heirs of Jewish collectors recover works of art that Nazi Germany had looted.

Under the terms of the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, or the Washington Declaration as it is commonly known, this worthy objective was to be completed within several years. In retrospect, the sponsors of the conference, the U.S. State Department and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, were far too sanguine about the timeline.

Two decades on, approximately 500,000 paintings stolen by the Nazis have been returned to their rightful owners, but the fate of about 100,000, some in museums and still others in private collections, has yet to be settled.

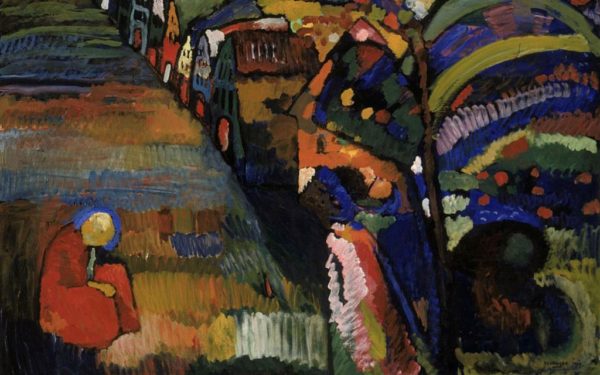

One of these contested paintings, “Painting with Houses,” an Expressionist piece by Wassily Kandinsky finished in 1909, is now at the centre of an international row that really began with Germany’s invasion of Holland in 1940.

Five months after Germany’s occupation of Holland, Irma Klein and her husband sold this painting to the Stedelijk Museum at an auction in Amsterdam for the modern-day equivalent of about $1,600. Their descendants claim the Kleins were pressured to sell it because they needed funds to survive the rigors of the Holocaust.

By all accounts, this oil on canvas could fetch tens of millions of dollars today were it to be sold.

Last year, the Dutch Restitution Committee — an advisory body created 17 years ago by the Dutch government — concluded that the Kleins had been forced to sell the painting for an unreasonably low price.

But in another ruling, the committee, consisting of art historians and lawyers, stated that it should be continued to be displayed at the museum due to “public interest,” and that it should not be returned to the family.

Understandably enough, the Kleins’ descendants were shocked and appalled because Holland is widely regarded as a model of art restitution practices.

In the wake of the Washington Declaration, Holland was one of only five countries, apart from Germany, Austria, Britain and France, to establish special committees to determine the provenance of suspect paintings.

Sadly enough, the Dutch Restitution Committee was already embroiled in a similar lawsuit filed by Bruce Berg, the grandson of the late Benjamin Katz and a great-nephew of the late Nathan Katz, the proprietors of an art gallery in Amsterdam.

Berg claims that 143 of these paintings, produced by Dutch old masters such as Pieter Claesz and Jan Steen, were owned by the Katz brothers and were sold or traded under duress to Nazi representatives between 1940 and 1942. These paintings are now in the wrongful possession of the Dutch government and of private and public museums in Holland, says Berg.

Berg’s lawyer, Joel Androphy, has been quoted as saying, “The paintings were destined for Adolf Hitler’s future Führermuseum in Linz, Austria, or for the massive art collection of Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring.”

It seems clear that, at the very least, the descendants of both families should be offered monetary compensation for the paintings their ancestors were compelled to sell or trade for a pittance under the worst of circumstances.

It’s disappointing that the Dutch Restitution Committee did not even raise this issue in its report.