America in the 1930s seemed like fertile ground for the rise of home-grown fascism.

Consider the anecdotal evidence.

Increasing numbers of Americans were open to the wholesale transformation of the United States into a fascist dictatorship. Financially and psychologically hobbled by the Depression, they were receptive to authoritarianism and antisemitism. And they were inured to racial segregation and in thrall to white supremacism.

Americans during this dark and unstable period were presented with alternatives. They could tolerate the status quo in the hope of refreshing and reforming democracy. They could experiment with communism, the system of governance in the Soviet Union. Alternatively, they could choose fascism, which had been adopted by Italy and Germany.

The German American Bund, a subversive antisemitic organization which appealed to some German Americans, tried to exploit this unease and discontent to its advantage.

Formed in 1936 by Fritz Kuhn, a naturalized German American, it flourished for about five years before its collapse following Kuhn’s arrest, Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, and Germany’s declaration of war against the United States.

Its precipitous rise and fall is charted in Nazi Town, USA, an absorbing and chilling one hour PBS documentary by Peter Yost which premieres on the American Experience platform on Tuesday, January 23 at 9 p.m. (check local listings).

Melding patriotic values and virulent antisemitism, the German American Bund cloaked itself in traditional American symbols ranging from George Washington to the Stars and Stripes. It promoted the preposterous idea that the average citizen could be simultaneously a patriot and a Nazi.

Viewed from its partisan perspective, it was a quintessential American organization. Flaunting its unique version of star-spangled fascism, it called for a “socially just, financially independent, gentile-controlled and Jew-free America” at a time when American racists were denouncing President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal as the “Jew Deal.”

Kuhn’s racially-charged, divisive message did not fall on deaf ears. At its peak in 1939, when membership swelled to about 100,000, the German American Bund was riding high.

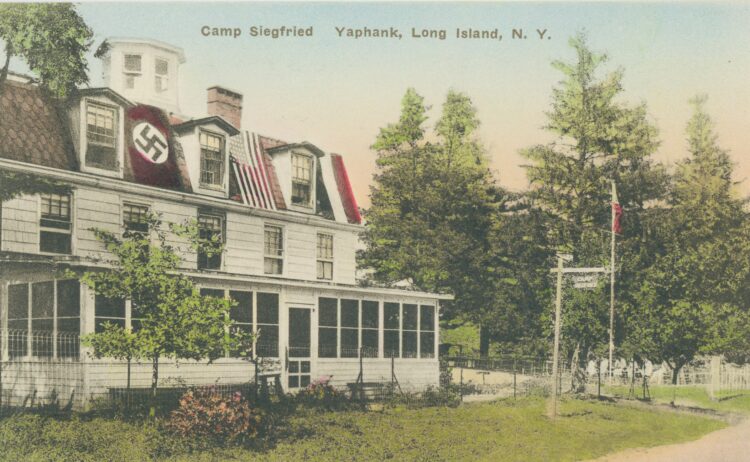

With headquarters in Yorkville, in Manhattan’s Upper East Side, it was active in 45 regional districts in the United States. Its nation-wide summer youth camps, such as Camp Nordland in New Jersey and Camp Siegfried in Long Island, brainwashed a generation of young German Americans. And its planned community in Yaphank, Long Island, known as German Gardens, allowed racists to isolate themselves from polyglot mainstream America.

The German American Bund’s popularity was not all that surprising in light of the reactionary ideas and movements that bubbled to the surface during this epoch, the American historians Arnie Bernstein, Sarah Churchwell and Beverly Gage point out in brief commentaries.

The Ku Klux Klan, with four to five million members during the mid-1920s, espoused a melange of white Christian nationalism, antisemitism, segregation, anti-African American bigotry and family values.

The eugenics movement rationalized racism on scientific grounds. The U.S. Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act, which restricted immigration on the basis of racial criteria.

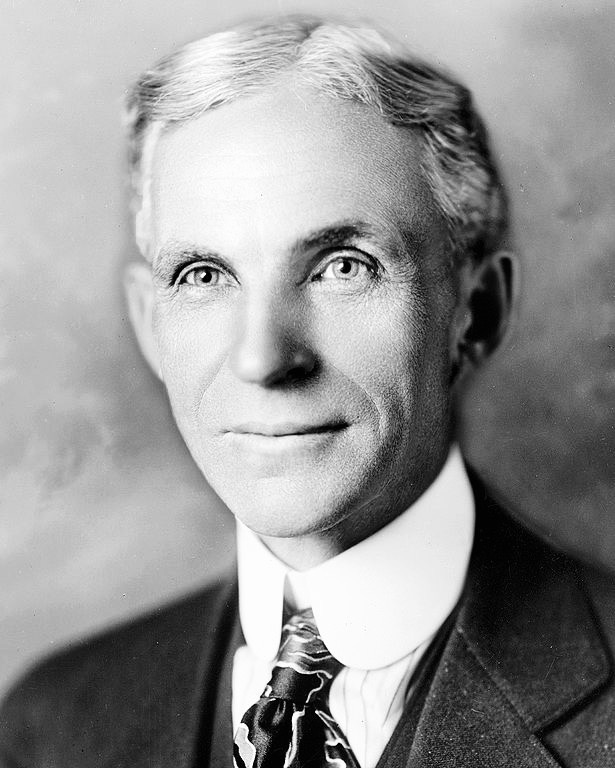

Henry Ford, the industrialist who symbolized America’s innovative entrepreneurial spirit, disseminated racist conspiracy theories, published an antisemitic newspaper, and expressed admiration of Adolf Hitler and his Nazi regime.

In 1929, the stock market crashed, ushering in an era of crushingly high unemployment, social dissolution and despondency and revolutionary fervor. Extremist groups, notably the Silver Shirts and the Paul Revere Sentinels, emerged to challenge the political order. Father Charles Coughlin, a toxic priest with an immense radio following, railed against Jews.

Monitoring this turmoil, Hitler’s regime created the Friends of New Germany, whose mandate was to sugarcoat the image of Nazi Germany in the U.S. One of its first recruits, Kuhn, had immigrated to the United States in 1924 and had found a job in Detroit as an Xray technician in Henry Ford’s empire.

With the collapse of the Friends of New Germany, Kuhn founded the German American Bund, which grew by leaps and bounds. However, the majority of German Americans were cool to its ideological orientation and radical plank.

Roosevelt, in 1937, ordered the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, J. Edgar Hoover, to investigate Kuhn’s outfit. The FBI produced a voluminous report, but Hoover sat on it because he regarded communism as a greater threat to the United States than fascism.

The Chicago Daily News published a damning series of stories on the German American Bund in the same year, exposing its secret plan to establish a dictatorship after a revolutionary upheaval. For Kuhn, these articles were a public relations disaster, galvanizing public opinion against his organization.

The German American Bund reached its apogee of influence in February 1939, when 20,000 of its supporters filled Madison Square Garden in Manhattan to attend what was billed as a “pro-American rally.” Ten thousand angry protesters milled outside, denouncing the event.

With blown-up images of George Washington hanging next to swastikas, a procession of speakers condemned the “Jewish-controlled media” and endorsed the notion of a racially “pure”America.

Embarrassed by this racist spectacle, the half-Jewish mayor of New York, Fiorello LaGuardia, opened an investigation of Kuhn. Investigators discovered he had misused organizational funds to finance his extramarital affairs around the country.

Convicted of embezzlement and income tax evasion, he was sentenced to a two-year prison term. Shortly after his release, he was charged with failure to register as a foreign agent. Once again, he found himself behind bars. In 1945, he was stripped of his U.S. citizenship and deported to Germany, where he died in obscurity.

Absent Kuhn’s leadership and the entry of the United States into World War II, the German American Bund floundered and passed from the scene. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of Americans continued to support and join far right-wing organizations such as Charles Lindbergh’s America First Committee, which denigrated Jews and sought to keep the United States neutral and out of the war.

Nearly 80 years after Kuhn’s deportation and Lindberg’s exhortations, the German American Bund and the America First Committee have been largely forgotten. But the dangerous ideas and isolationist sentiments they respectively tapped into have not vanished from politics in the United States, reminding viewers that American democracy is both fragile and resilient.