German scholar Matthias Kuntzel provides readers with a ground-breaking theory about Arab/Muslim hostility to Israel and Jews in his penetratingly incisive book, Nazis, Islamic Antisemitism And The Middle East: The 1948 Arab War Against Israel And The Aftershocks Of World War II (Routledge).

A political scientist and historian, he argues that antisemitism in the Arab world was not mainly a response to the birth of Israel, but rather a manifestation of ingrained animus toward Jews colored by Nazi hatred.

He bolsters his argument by claiming that the Middle East was the only region in the world where admiration of the Nazi regime was rampant following Germany’s defeat in 1945.

Kuntzel’s thesis will be heatedly challenged by Arab commentators, but the fact remains that the impact of Nazi ideology on Arab societies is, as he contends, a “gravely under-researched” area of study. “My book aims to fill this gap to the extent currently possible,” he writes in a reference to the archival material that researchers can access at the moment. But in a caveat, he acknowledges that the topic requires further research.

Kuntzel focuses on the decade between 1937 and 1947, which were momentous years in the region.

Britain, which held the League of Nations mandate in Palestine, offered the first proposal for a two-state solution in 1937. An incendiary pamphlet published in Cairo in the same year, Judaism and Islam, linked the prophet Mohammad’s conflict with Jews in Medina with the contemporary Arab-Jewish conflict in Palestine. In 1947, the United Nations endorsed the creation of a Jewish and an Arab state in Palestine, a resolution that the Arabs vehemently rejected.

Kuntzel begins his inquiry with an examination of the roots of enmity toward Jews in Muslim societies.

Mohammad was initially an admirer of Jewish traditions and beliefs, hoping that Jews would convert to Islam and support him in winning over Arab pagans. But when Jews resisted his overtures, he adopted a hostile attitude toward them. From that point forward, Jews were protected as a tolerated minority on condition that they accepted their second-class status.

Kuntzel notes that, while Muslim rulers offered Jews more security than Christian authorities, they were nevertheless “systematically oppressed and humiliated.” He contends that “this imperative to humiliate has remained a characteristic of Muslim Jew-hatred to this day.”

During the 20th century, he adds, negative images of Jews in Islam and Christianity fused. As he puts it, “The traditional Islamic images of Jewish weakness and cowardice are linked with the Western conspiracy paranoia about Jews secretly pulling the strings.”

He cites examples.

Sayyid Qutb (1906-1966), the most important ideologue in Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, lambasted Jews in his essay “Our Struggle with the Jews.” As he wrote, “The Jews … plotted against the Muslim community from the first day it became a community.”

Haj Amin al-Husseini, the mufti of Jerusalem during the British mandate, justified his animosity toward Jews on religious grounds, Kuntzel argues. But this is only a partial explanation. Husseini, a zealous opponent of Zionism, was obviously motivated by nationalist motivations as well.

More recently, Hamas’ charter, released in 1988 and modified in 2017, accused Jews of seeking to destroy Islam.

As for the Koran, it contains verses both praising and defaming the “children of Israel.”

In chapter two, probably Kuntzel’s most comprehensive one, he discusses the appearance of European-style antisemitism in Arab states. Christians in the Ottoman Empire, as well as foreign priests and diplomats, promoted toxic notions accusing Jews for the ills of society. He cites the Damascus affair of 1840, during which Franciscan monks and the French consul accused Jews of blood libel, and the antisemitic demonstrations mounted by French colonialists in Tunisia in 1898 during the Dreyfus affair.

He goes on to say that the first Arabic edition of the Protocols of the Elders a Zion, a notorious czarist forgery concocted by the Russian secret police, appeared in Palestine in 1918. Inspired by its publication, the Palestine Arab Congress submitted a memorandum to British Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill lambasting Jews as a destructive force.

At this point in his narrative, Kuntzel focuses on Germany, saying that the Nazi regime first began taking a “serious interest” in Palestinian Arabs after a British government commission recommended the partition of Palestine.

While a minority of Palestinians were prepared for territorial compromise, the majority, represented by the mufti of Jerusalem and his acolytes, were bitterly opposed to the plan, as was Germany. In 1937, two emissaries of the mufti met the German envoy in Baghdad, Fritz Grobba. From that point forward, Germany lent tangible support to the Palestinians and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, supplying both groups with arms and funding.

Kuntzel cites an incident in 1944 during which five parachutists, comprised of three Palestinian-born German army officers and two local Arabs, were captured by British forces after landing in the Jordan Valley, where they had hidden crates of weapons.

In the summer of that seminal year, the Germans began distributing the Arabic edition of Islam and Judaism in the Middle East. Its publisher, Mohammad al-Taher, was a journalist and the director of the Palestinian Arab Information Office in Cairo. Kuntzel thinks the mufti may have been its moving spirit or author, but he offers no compelling proof. Still, one can easily imagine that the mufti’s fingerprints were all over this incendiary pamphlet.

The Nazis also supported the Palestinian/Arab cause through Arabic language radio broadcasts from April 1939 until April 1945. They promoted an exclusively anti-Jewish reading of the Koran, demonized Zionism and accused Jews of being enemies of Islam who fomented strife and disseminated communism. The tone of these broadcasts turned still more radical after the mufti was granted an audience with Adolf Hitler in Berlin in 1941.

By way of example, Kuntzel reproduces a broadcast from July 1942 that advocated mass murder: “Kill the Jews, burn their property, destroy their stores, annihilate these base supporters of British imperialism. Your sole hope of salvation lies in annihilating the Jews before they annihilate you.”

Broadcasts of this type had already emboldened Arab antisemites and would push them in the same direction even after the war. Two examples will suffice. In June 1941, Iraqi nationalists sympathetic to Germany massacred 180 Jews in a pogrom in Baghdad known as the farhud. Kuntzel believes the mufti was involved in this atrocity. Six months after the war, Hassan al-Banna, the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, participated in a mass demonstration in Cairo that ended with the first pogrom in Egypt’s modern history, with mobs breaking into Jewish-owned shops and desecrating synagogues.

As Kuntzel observes, the establishment of Israel and the generally lackluster performance of Arab armies in the war that followed also fuelled Arab rage and antisemitism.

Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s authoritarian ruler from 1952 to 1970, allowed the Protocols of the Elders of Zion to be published and circulated and employed scores of Nazi war criminals in the bureaucracy and the armed forces.

Among the Nazis who settled in Egypt were Aribert Heim, a physician who conducted grotesque medical experiments on Jewish prisoners in the Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald and Mauthausen concentration camps; Alfred Zingler, who had worked for Joseph Goebbels in the Ministry of Propaganda and who helped establish the antisemitic Institute for the Study of Zionism in Cairo, and Erich Altern, a Gestapo agent who was a military instructor in Palestinian training camps.

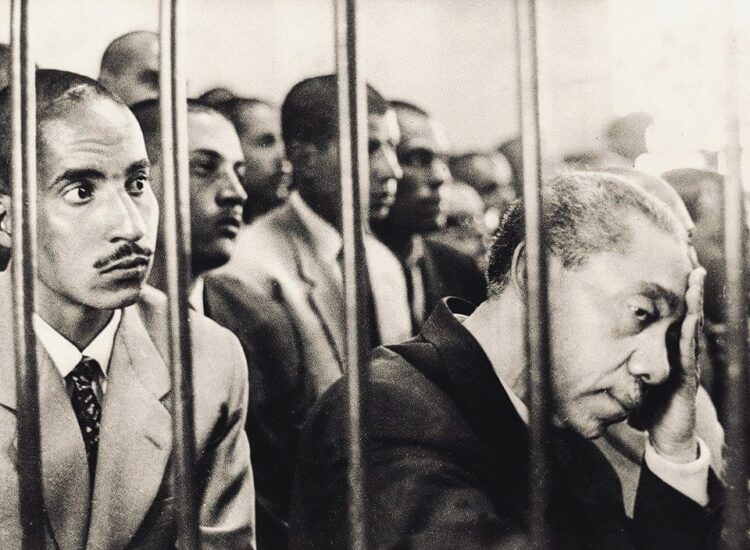

On a broader basis, public opinion in the Arab world concerning Hitler and his regime sharply diverged from the global consensus that they were the epitome of evil. In the aftermath of Adolf Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem, the German Jewish political scientist Hannah Arendt wrote, “The papers in Damascus and Beirut and Jordan did not hide their sympathy for Eichmann nor their regret that he ‘did not complete his business.’ A radio broadcast from Cairo on the day of the trial’s opening even took a little sideswipe at the Germans, reproaching them for the fact that, ‘in the last war not one German airplane had flown over and bombed a Jewish settlement.'”

In summation, Kuntzel reiterates his argument that Israel is not the sole cause of antisemitism in the Arab world. “The very existence of the 1937 pamphlet Islam and Judaism, which repeatedly refers to the essential hostility between the Jews and Islam, disproves the idea that Arabs would get along with Jews after a victory over Zionism. Even then, the pamphlet’s Arab version explains, Allah will ‘break their spines.'”

To drive home his point, Kuntzel refers to a 2014 Anti-Defamation League study that showed that 75 percent of Muslims surveyed in the Middle East agreed with a wide range of antisemitic tropes and stereotypes. And to this day, Palestinian leaders such as Mahmoud Abbas, the president of the Palestinian Authority, hold the mufti in high regard as a hero.

In closing, Kuntzel suggests that Nazi propaganda has had a lasting effect on the mindset of many Arabs. Proceeding from that assumption, he believes that Palestinian “ideological blocks,” rather than “Jewish settlement blocs” in the West Bank, present the “biggest obstacle” to peace and reconciliation between Israelis and Palestinians.

His thesis is certainly credible, but Israel’s occupation of the West Bank, with its array of Israeli settlements, also blocks a resolution of its conflict with the Palestinians.