Rafi Nelson was a character par excellence, a legendary Israeli entrepreneur whose Red Sea beach resort was synonymous with a bohemian, hedonistic lifestyle.

Rafi Nelson’s Holiday Village was located in Taba, a one square kilometer enclave in the northern Sinai Peninsula adjacent to Israel’s border with Egypt. It attracted an eclectic clientele of ordinary and well-placed Israelis and foreign celebrities.

Nelson, a former journalist and public relations consultant, started it with a single tent in 1970 and ran it with zest and passion until his untimely death in 1988.

Under the terms of its peace treaty with Egypt in 1979, Israel agreed to withdraw from the Sinai, which it had captured in the 1967 Six Day War. There was sticking point — Taba, which Israel insisted on keeping. Nelson did everything in his power to ensure that Taba would remain in Israeli hands.

Nelson’s titanic struggle forms a huge chunk of Avi Maor-Marzuk’s endearing documentary, Nelson’s Last Stand, which will be screened at the Toronto Jewish Film Festival on June 5.

By chance, the screening coincides with the 56th anniversary of the outbreak of the Six Day War, which changed Nelson’s life.

Nelson, whose real surname was Rosenzweig, managed a nightclub in the port of Eilat when that war broke out. Like many Israeli visitors who ventured into the Sinai after Israel’s overwhelming military victory, he was awestruck by its stark and rugged beauty.

Fixated on Taba, with its sandy beach and mountainous backdrop, Nelson created his own private version of paradise in this corner of the Sinai desert without the benefit of electricity or running water.

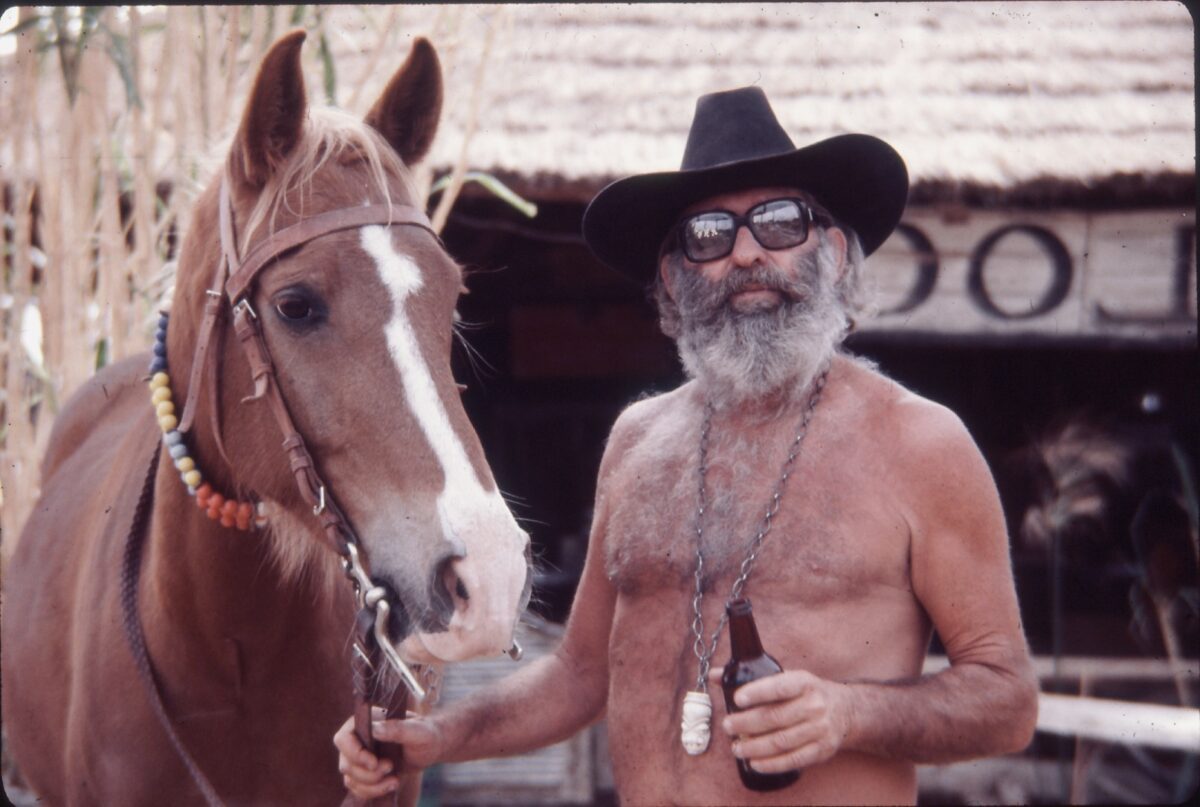

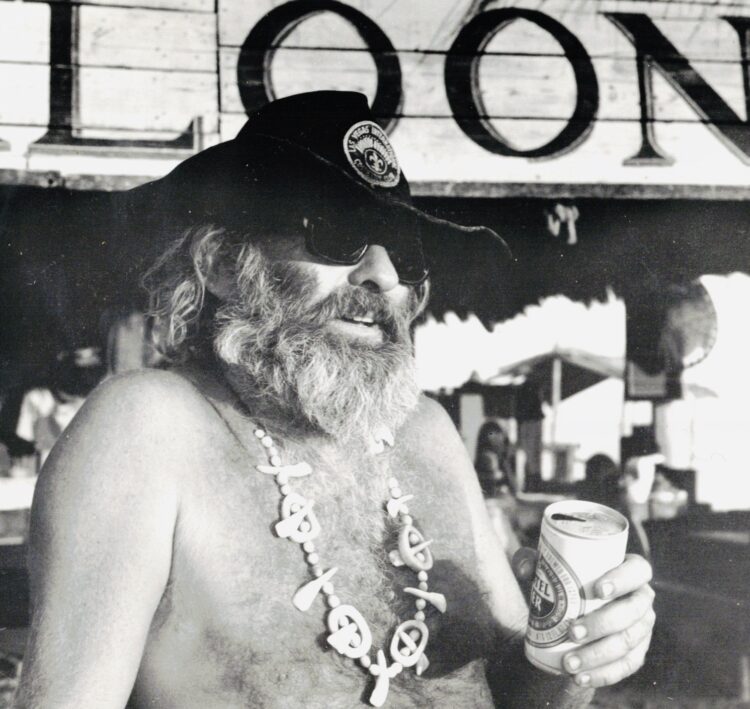

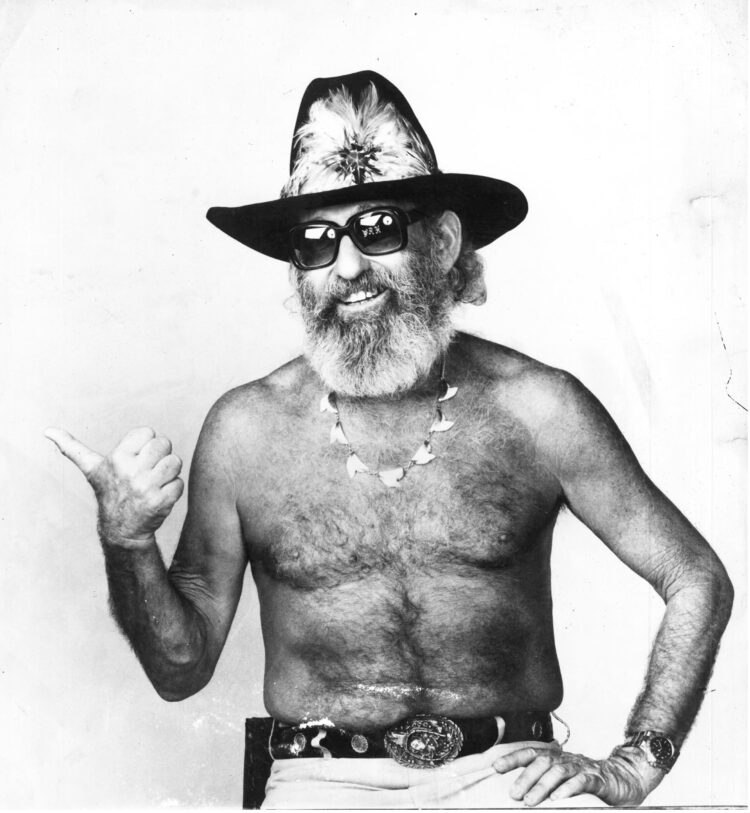

He stood out in a crowd. A scruffy, bearded figure clad in a cowboy hat, with a shark-tooth necklace dangling from his neck, he always wore sunglasses, which shielded a black eyepatch, and was rarely seen without a bottle of cold beer in his hand.

He was a ladies’ man and his resort, signifying sun, sea and sex, exuded an atmosphere of debauchery fueled by alcohol and hashish.

Nelson may have been forgiven for assuming that Taba would remain an Israeli possession for time immemorial. Menachem Begin, Israel’s hawkish prime minister, had allowed a real estate developer to build a luxury hotel in Taba, the Aviva Sonesta. Begin’s defence minister, Ariel Sharon, had personally assured Nelson that he need not worry about Taba’s future. Sharon’s successor, Ezer Weizman, gave Nelson an identical assurance.

Buoyed by these promises, Nelson assumed that his resort was here to stay and boasted that he would never leave Taba. Egypt claimed that Taba was in Egyptian territory, and its president, Hosni Mubarak, compared it to a father’s child that had to be returned.

Israel completed its pullout from Sinai in April 1982, with Taba still under its control. Israel’s invasion of southern Lebanon a few months later delayed a resolution of the problem. In the mid-1980s, Israel agreed to settle this vexing issue through arbitration, but insisted that a 1906 British survey of Sinai proved beyond any reasonable doubt that Taba was inside sovereign Israeli territory.

In the meantime, Nelson launched a media campaign to retain Taba, saying he would rather give up Jerusalem than part with Taba. Flouting the rules, Sharon slyly moved an old border marker closer to Eilat to prove that Taba lay within Israel.

Nelson, only 58 and newly married, died of a heart attack before the issue could finally be settled.

Nelson’s Last Stand can be regarded as a cinematic monument to a man who loved life and adored the iconic but doomed resort he built from scratch.